from Century Magazine

The Blind Ass of the 'Dobe Mill

by Ellis Parker Butler

The great white mules went by with the jingling of many bells and the merry cracking of whips, and the little gray ass of the 'dobe mill, treading his interminable round, pricked up his long ears and for a moment stepped the faster; but as his course around the clay mill led him around the circle to the left, he dropped back into his slowly patient pace.

"The white mules have turned down a road to the right," said the little gray ass to himself. "But what odds? Had we been taking the same road, I should soon have been left behind. Blessed be Mary! that such as I may even for a moment tread beside the great white mules."

The little gray ass was blind, and he was old, for in the clay mill there is no advantage in eyes that can see. For three years he had been walking the well-beaten path around the clay mill, led by a rope attached to a boom that always preceded him, and dragging the heavy boom that turned the mill. At one point of the track a huge olive tree threw a shadow. Sometimes, when the days were hot, Pedro allowed the little blind ass to rest in the shade of the olive tree.

"Blessed be the kind master!" the little blind ass said to himself then. "The road is long, but there are many olive trees, and sooner or later he allows me to rest under one of them. Truly man is kind, for, blind as I am, how should I get my food had not my master taken pity on me? Every night he finds me a safe place in which to rest, every day he sees me well fed, and in return he asks nothing at all. For three good years now I have had naught to do but live well and travel from place to place, seeing the country."

When his master spoke to him, the little blind ass would turn his long ears quickly to catch every word of the voice. Never was there such a master.

"See, now," said the little blind ass, "another would beat me with clubs; but my master has only a whip with which he urges me on when I stop, lest, perchance, some great cart laden with oil crash into me to my harm. He is a good man, and skillful, for never has he led me into harm's way. He picks the part of the road that is free from stones and ruts that would trip a poor blind ass."

Then he would tread on, led by the rope that was attached to the boom.

In three years the little blind ass had seen many pleasant things. Now and then a party of laughing youths and maidens would pass along the road that lay beside the clay mill, and the little gray ass would raise his long ears.

"Good, then!" he would say to himself. "We have come to a market town, upon a market day. It is a pretty sight."

Sometimes an old woman would pass, carrying a basket of garlic.

"One thing after another, but always a pleasant variation," the little blind ass would then say as he sniffed the odor. "We have come to the farmland again."

Thus round and round he walked, always in the same little beaten circle of path, and at night he rested always in the same stall in the same little 'dobe stable. At first Pedro had to lead him to the stall, but in time the little blind ass learned the path to the stall himself, and when the traces were cast loose and the halter untied, off he would go to his stall.

"Now, blessed be mankind," he would say, "for making easy the path of all blind asses! The world moves. In my seeing days the stables were of a thousand kinds, set in a thousand ways, fit to worry the wisest, but now each is as like all the others as one oat is like another. Truly, man eases the way for blind asses. At the end of each day's travel there is a stable, and each stable like unto the others, and the path from the road to each stable alike, even to the post midway, against which a creature may rub his sides."

For a week or more, at the first, the little blind ass had worried regarding one point -- the end of the journey. For, like all the world, the little blind ass worshiped the god Terminus, as all thinking creatures do, offering him incense of worry in one form or another. Only historians and scientists -- who are only the historians of matter and mixtures of matter -- bother much about beginnings, but every wise man desires to know "how this thing is going to end." But as his journey stretched out day after day and year after year, and seemed likely to stretch out years and years more, the end seemed to matter less to the little blind ass.

"No doubt my master knows," he said to himself; "and if he knows, he has no cause to worry, so why should I? And if he does not know, why should I bother about it at all, who know so much less than he? Should he, at the end of the journey, decide to turn back, what more pleasant than to revisit the scenes I have passed? And should he decide to continue farther, what more pleasant than to see new scenes?"

So, like a wise little blind ass, he worried no more, and let the god Terminus look out for himself.

But a three-years' journey is not all downhill. Often, every day, the workmen dumped more clay into the clay mill. Then, as the little blind ass felt the new weight, he tugged the harder at the traces.

"Here we have a pretty hill," he would say to himself, "and the good saints be thanked for hills; for what would a road be like that was all as level as a floor? At the tops of the hills are the cool breezes."

So he would tug away at the traces until the clay worked out at the bottom of the mill and the pull on the traces became easier.

"As I said," he would say to himself, "the breeze is much finer here on the hilltop, and now for down the other side!"

And sometimes he would break into a little running step down that hill. Then Pedro would laugh and say: "Whoa! Don't run away from us, sweetheart!" That always pleased the little gray ass.

For three years the little gray ass plodded round the narrow circle of the clay mill, seeing the world on his travels, and at the end of three years his heart was younger than at the beginning; but as for Pedro, his master, it was another matter. At the beginning of the three years he was a boy, with no heart at all; but at the end he was a man. At the end of three years he had soft hairs on his upper lip, and when he set his hat jauntily on one side of his head, it was no longer from boyish joy, but because 'Rita was coming down the road that passed the clay mill.

That was a bad business, that about 'Rita. She was no sort of girl at all for an honest lad like Pedro. The yellow-skinned loafers before the wine shop, smoking their cigarettes, spoke to her boldly when she passed.

"Hello, 'Rita!" they said, and when she had passed by they shrugged their shoulders and grinned. Why, her mantilla alone cost -- But what did the little blind ass know about mantillas?

He only knew when 'Rita passed the clay mill. Her lips were redder than nature permits lips to be, -- for the peace of mankind, I suppose, -- and her eyes sparkled, and she wore a rose in her black hair for coquetry; but none of these things were known to the little blind ass. Only two things he did know. When he heard her light step on the road and her soft voice as she spoke with Pedro, the little blind ass stood still.

"Ah," he would say to himself, "now we have got somewhere at last! Now we are arrived at the court, or at least at the estate of a great man; for the ladies are light of foot and soft of voice. A creature may rest here a while and flap the flies from his sides like an aristocrat."

Then his gray nostrils would twitch delightedly. Many maids passed the clay mill from one month to another; some bore garlic, and some bore wine in skins, and some bore gleanings of the wheat, and of each there was its own particular odor, and the little blind ass would cock his ears wisely.

"We are passing the garden, the vineyard, the fields of wheat," he would say to himself. "This is a fine country we are passing through."

But when 'Rita passed he held his ears most erect, and his nostrils swelled to their widest, and he turned his head as far her way as the leading halter would allow; for she had upon her toilet-table in the old stone house back of the bodega a vial of perfume sent from Seville itself by that mythical uncle of hers.

"At last," the little blind ass of the clay mill would say, "we have reached the pleasant valley of flowers. Fine country there to the right! Valley lilies, roses -- whiff! Sniff! Um! Fine place for a young fellow such as I was once to kick up his heels and nibble blossoms."

But though he stretched out his head, Pedro never unharnessed him, and the little gray ass went on contentedly when 'Rita, leaving a whiff of the perfume behind, passed on her way.

"All for the best!" said the little blind ass of the clay mill. "I'm past the age for nibbling blossoms. Give me a rich, tough thistle any day. And as for thistles, hay is preferable. Blessed be St. Nebuchadnezzar!"

So day after day he walked around the clay mill path, seeing far lands, -- seeing fields of grain, and hillsides rich with ruddy grapes, and pleasant villages, -- and every week the country became more beautiful in the blind eyes of the little gray ass; for the fields of flowers became more and more plentiful.

Which is only saying that 'Rita stopped more and more often to chat with Pedro.

"Good word!" said the little blind ass. "No wonder my master has driven me so far, for such a land of blossoms was well worth seeking. It is a pleasure to wander through such a land."

"What do you think?" said the yellow loafers before the wine shop. "Pedro is going to marry 'Rita!"

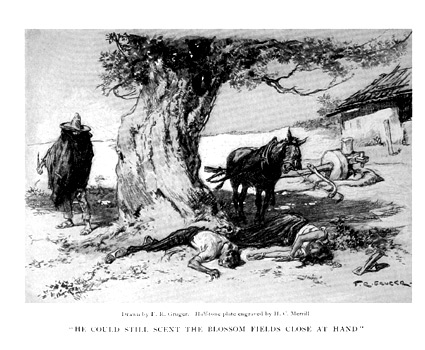

"Fool!" they said. But there was one -- Jose -- who said nothing. He slipped away from his fellows and glided up the straight road until he saw 'Rita, one hand on the great olive tree, talking with Pedro, while the little blind ass rested in the shade of the tree, very happy and very content. As Jose crept closer, the little blind traveler closed one eye and then the other. He was awakened by the angry voices of Jose and his master. He heard, too, the weeping of 'Rita. He heard the voices grow louder, and a woman's shriek of anger, dying into agony and silence, and the sound of men's voices panting in a struggle, and a gasp, and the hurried noise of a pair of feet running away down the road.

For minutes more the little blind ass of the 'dobe mill stood awaiting the word of command from his master. He could still scent the blossom fields close at hand. From time to time he raised his long ears. No doubt his master had gone to pick blossoms.

He stood until the sun, moving westward, carried the shadow of the great olive tree to one side and the sunlight fell on his flanks. Then he leaned forward and put his weight against the yoke, and patiently moved on around the beaten path that surrounded the clay mill.

"Dallying with the flowers is well enough," he said to himself, "and I would willingly stand all day; but wisdom comes with years, and I must get on my way, or I shall not reach the stable, with its sweet hay, by sunset."

And around and around the beaten path trudged the little blind ass of the clay mill.