|

|

from American Girl

Jo Ann and April Fool

by Ellis Parker Butler

Jo Ann sat with her chin in her hands, and Wicky sat with her chin in her hands, and both were frowning hard, because they were thinking harder than they had ever thought in their lives.

"Oh! Shut off that thing!" Jo Ann exclaimed. "I can't think when it's blatting that way!"

Wicky got up and shut off the thing, which was a fine big cabinet radio that Jo Ann had received that very morning from her uncle Peter. Mike, the porter of Wilmot School, had rigged up an antenna around the picture molding not two hours before, and the radio was delivering the song Old Man River in a way Jo Ann had said, only a little while before, was "absolutely suave," but now it was driving her simply mad. She had to think, and she couldn't think, and that is a thing that makes anyone cross.

"We could make some chocolate creams and send them to him," Wicky said, "and put soap in them instead of cream fondant," but she said it without much interest. She knew it was a sickly idea.

"Puh!" said Jo Ann scornfully. "That's a thousand years old; it wouldn't fool a rabbit. For goodness' sake think of something, can't you? If you can't, keep still and let me think."

From where Jo Ann sat she could see out of the window and across the valley. She could see Spenceville Academy sitting on its hillside, and she knew that somewhere in the academy red-headed Tommy Bassick was planning an April Fool joke on Jo Ann, a joke that would be as terrible and disconcerting and overwhelming as an April Fool joke could be,

and -- in their room at Wilmot School -- Jo Ann and Wicky were trying to think of an April Fool joke to play on Tommy Bassick, a joke that would be more terrible and more disconcerting and more overwhelming than any that Tommy Bassick could ever possibly think of. But the trouble was that Jo Ann and Wicky could not think of any joke at all that would work. This made it a very sad and exhausting business. If Jo Ann had been at home, and if Tommy Bassick had been at home, it might have been easy enough, because then Tommy would have been somewhere where Jo Ann could have got at him. But with Tommy Bassick in the academy and Jo Ann in Wilmot School, it was very hard. If you sent him candy, he would know it had soap or potato in it just because it arrived on April first, and he wouldn't bite it; if you sent him ginger ale with salt or quinine in it, he wouldn't drink it -- and when an April Fool joke doesn't work it is a joke on you for trying it, and Tommy Bassick would send the stuff back with an "April Fool yourself!" It was enough to break a person's heart.

"Oh, drat!" Jo Ann cried, kicking a black and gold pillow. 'I don't believe there's an April Fool joke in the world that isn't as old as the ark."

"Some of the old ones were pretty good," Wicky said meekly. "It doesn't have to be so awfully complicated. We could telephone him, and then when he answers, say 'April Fool.'"

"He won't answer any telephone, not on April Fool day," Jo Ann said. "He wouldn't even open a telegram; he's not that dumb."

"If we could get him to come over here --" Wicky said.

"Oh! don't be silly!" exclaimed Jo Ann crossly. "You know he won't come on a day when we want to fool him; he has some sense, even if he is a boy. Do try to think of something, Wicky. My ideas are simply wrinkled with age."

"I am trying," Wicky said even more meekly, and Jo Ann said "Huh!" in a way that indicated that she did not think much of the kind of thinking Wicky was doing. She got out of her chair and picked up the black and gold pillow and thrust it into the chair, and gathered up her discarded underwear, which she had left scattered on the floor. She opened the closet door.

"Wicky!" she exclaimed suddenly.

In the closet, and pretty well filling its lower part, for the closet was not big, was the box in which the cabinet radio had arrived. It was a box made of the corrugated brownish paper that most things are shipped in these days, the corners and edges reinforced with linen strips that were glued on -- a good stout box and light in weight for its size. Mike, the porter, had wanted to take it away when he had unpacked the radio, but Jo Ann had made him leave it. The box would be needed when the radio was shipped home, and in the meanwhile, Jo Ann said, they could dump their soiled laundry in it. Now it gave her a splendid idea.

"Wicky," she cried triumphantly, "I've got it! Oh! I've got the swellest idea! If we don't have a laugh on Tommy Bassick! Come here! Look at this box!"

Wicky went to the closet door.

"Look at it!" Jo Ann said. "Look, at the size of it. Stupid! Doesn't that suggest anything to you? We'll send Tommy Bassick a radio set!"

"Jo Ann!"

"He'll never suspect it's a joke,"' Jo Ann ran on in the excited haste of an explorer who has just made a great discovery. "In the very last letter mother wrote me -- the one in which she said Uncle was going to send me a radio -- she said that Mrs. Bassick had told her that Tommy was asking for a radio, but she hadn't made up her mind yet whether to send him one or not. She said maybe she would and maybe she wouldn't, it is so near the end of the year, and they -- Mrs. Bassick and Mr. Bassick -- had written Tommy they hadn't decided. So don't you see --"

"Jo Ann, you aren't going to send him your radio, are you?" Wicky asked anxiously.

"Of course not, silly!" Jo Ana laughed. "I'm going to April Fool him. We'll fill it with --"

Suddenly she grabbed Wicky by both arms.

"Wicky!" she cried. "I know! I know! I have got it now! When I see his face when I --" She stopped. "But perhaps it had better be you," she said, looking Wicky up and down.

"Jo Ann, what on earth are you talking about?" Wicky asked.

"Well, you're shorter than I am," Jo Ann said. "Shorter and plumper -- I don't mean too plump, Wicky, because I'll probably wish I was as plump as you are pretty soon; they say it's going to be the style to be plumper and I think you're just about right -- but you do weigh nearer to what the radio set weighs."

"What do you mean?" Wicky demanded. "I mean you'll fit in the box better," Jo Ann said.

"This box?" Wicky asked suspiciously, her head cocked.

"It's the only box we've get, isn't it?" Jo Ann asked. "I wouldn't mean any other, would I, for goodness' sake?"

"Do you mean I have to get in this box?" Wicky asked.

"Now, Wicky Wickham, don't you start being stubborn just when I've thought of the best joke on Tommy Bassick, please! I think you might be some kind of a sport, Wicky Wickham!"

"But, Jo Ann," said poor Wicky. "I am a good sport, and you know I am. Only I don't understand. Do you want me to get into this box?"

"Oh, don't be so stupid!" Jo Ann cried. "Of course I do! I've been saying so, haven't I? Don't you see? You'll get in the box, and I'll seal it up, only, of course, I'll leave an air-hole so you can breathe, and we'll address it to Tommy Bassick, at Spenceville Academy, and get Joe Higgs to take it there in his truck. And a radio set is the one thing Tommy Bassick will be expecting, and it is the one thing he won't think I'd think to send him for an April Fool. And then, when he opens it -- opens the top lids -- up you'll pop and shout 'April Fool!' at him and -- run! Jump out and run and I'll be waiting for you here."

Wicky did not say anything.

"Well," asked Jo Ann, "don't you think it's a peachy idea?"

"I think -- well, I think it ought to surprise him a good deal," Wicky admitted, but without much enthusiasm.

"Don't you think it is just a perfectly grand idea?" Jo Ann insisted.

"You mean they'll carry the box up to his room, and he'll shout and yell the way we did when your radio came, and a lot of boys will come to help him unpack the radio, and then I jump up and say 'April Fool' and run?" Wicky asked.

"That's it," Jo Ann said.

"Well, honestly, Jo Ann, honestly, I think you're the one that ought to be in the box," Wicky said. "I'd love to, Jo Ann -- you know that -- but you're so much better at shouting and running, than I am. You know I can hardly shout at all. Why, I might pop up and say 'April Fool!' and they might not hear me at all! But you can shout good and loud, Jo Ann. You're the one that ought to be in the box!"

"You can shout plenty loud," Jo Ann said. "You don't have to shout so they can hear you forty miles. Maybe if you just whispered it, it would be better. Just pop up and whisper 'April Fool!' Or you needn't pop up -- just stand up and say 'April Fool' and get out of the box and walk away. Scornfully, if you know what I mean, Wicky. Say 'April Fool, with Jo Ann's compliments!' and walk out haughtily."

"It ought to be somebody with longer legs than mine," Wicky said. "I couldn't step out of that box. You're the one to be in the box, Jo Ann; you've got long legs, you could step right out of it. It would be a lot better."

"No," Jo Ann said firmly. "You're going to be in the box, Wicky, and I'll tell you why. I've got forty-six demerits this term, and if I get four more they'll send me home, and whoever goes into the academy in a box this way is pretty sure to get ten demerits. You've only got twenty-six, so it won't matter to you, Wicky. If you get ten demerits it will only make thirty-six for you, and even if you get twenty it will make only forty-six."

"What if I get twenty-five?"

"Well, you won't," said Jo Ann positively.

"But if I do?"

"All right; if you do I'll just say it was all my fault," Jo Ann said. "I'll say I put you up to it and you didn't have sense enough to know it would get you into trouble. I'll let them send me home."

Wicky did not look forward to being Jo Ann's jack-in-a-box with any joy whatever. Being sealed in a box and jolted onto a truck and off a truck, and possibly over-ended up a couple of flights of stairs, and having the box opened in a room full of shouting boys did not appeal to Wicky us being the utmost pinnacle of pleasure. But to Jo Ann, it seemed a small thing for one friend to do for another, and she put it to Wicky so strongly that Wicky finally agreed to be the April Fool radio set.

It did not take Jo Ann long to decide what Wicky was to wear; her gymnasium suit seemed the best outfit for wearing in a corrugated paper-board box, being both neat and modest, and it was agreed that Wicky should wear her Girl Scout clasp knife, in case the authorities of Spenceville Academy ruled that Tommy Bassick could not have a radio, and stored the box in a cellar or storage room. There was no telling what demerits a boy like Tommy Bassick might have had piled up against him, and the radio might be kept from him as a punishment, and it would be extremely unpleasant for Wicky to be in a box on top of a pile of two or three hundred trunks for two months or so, until school was over, she said.

Preparing the label for the box was not much trouble. Jo Ann's radio had been sent from the leading radio store at home, and this was the store from which one would probably be sent to Tommy Bassick, if his parents decided to send him one, so all that was necessary was to change the name and address to Thomas Bassick, Spenceville Academy, which Jo Ann did very neatly. Neat air-holes were cut in the box in inconspicuous places, and Jo Ann got a small bottle of glue to be used in pasting the linen strip back over the place where the top of the box folded together like a pair of flat cellar doors, and Joe Higgs, when Jo Ann telephoned, him, said he would be on hand with his truck just about the right time the next day to make it appear as if the box had just arrived from Tommy Bassick's home.

In the meantime, at Spenceville Academy, Tommy Bassick and his friend and roommate, Ted Spence, were having headaches of their own, trying to think of an April Fool joke to play on Jo Ann. Ted Spence lay on his back on a couch, with his knees drawn up and his hands clasped behind his head, his brow in a deep frown, and his mind as absolutely blank as a sheet of white paper. At a desk in a corner of the room Tommy Bassick leaned over an open dictionary, one elbow on the desk and the hand of that arm grasping a handful of his red hair. The hair was still rooted in his scalp, but he pulled it now and then, as if trying to jolt up his brains in the hope that some idea might suddenly come up to the surface of his skull.

He was turning the pages of the dictionary in a hopeless sort of way, saying "femoral, femur, fen, fence," as he glanced down the columns, hoping to find the suggestion of an idea somewhere in the dictionary, but every minute his mind was getting fuzzier and more foggy.

"Fennec," he said. "Say, Ted; bet you a dime you don't know what a 'fennec' is."

"Fennec? It's a kind of weed, ain't it?" Ted asked.

"No, that's 'fennel'," Tommy said. "It says, 'Fennel, a perennial a-pi-a-ceous plant, with yellow flowers, cultivated for its aromatic seeds.' A fennec is a fox."

"Aw, it is not!"

"Listen -- 'Fennec, a small African fox, of a pale fawn color, remarkable for its larger ears.' Bet you a dime you don't know what a 'fenugreek' is."

"No, and I don't want to know," Ted said.

"'Fenugreek,'" Tommy read, "'an Asiatic fabaceous plant (Tri-go-nella foe-num-gra-e-cum) cultivated for its aromatic mucilaginous seeds.'"

"Yeh? Well, I'll tell you what you are -- you're a mucilaginous African fox with aromatic yellow ears. Come on, let's go out and kick a football around -- you'll never find a joke to play on Jo Annie in that book. Come on; I can't think of a thing. Come on, Tommy."

"Aw, wait a minute, can't you? 'Ferric, ferry, festal, fetish' Oh, punk! Come on, then! I'll go with you."

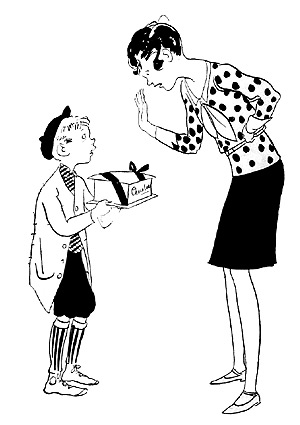

He slammed the book shut and banged it on the desk and reached for his cap, and the next day -- which was the first of April -- one of the things Jo Ann did was to refuse to accept from a small boy a box that was quite evidently a two-pound candy box, when the small boy brought it to her.

"Yes?" she said to the small boy. "Well, you kindly take this back to Tommy Bassick and say 'April Fool yourself.' Can you remember that?"

"Yes'm," said the small boy, grinning. "Listen --"

He rattled the box, and if it did not contain very hard candy -- which a chocolate cream box should not contain -- it must have contained a nice assortment of small stones, which is what it did contain.

"And now we'll see," she said when she had told Wicky of the weak attempt Tommy Bassick had made. "Mercy, Wicky; look at the time! We've got to hustle."

She ran to dump the soiled clothes out of the radio box. In it she put the gold and black pillow, so that Wicky might have something soft to sit on.

Wicky, patient martyr, was all ready. Her clasp knife was in her middy pocket, and she was fully clad in her gymnasium clothes. She put one foot into the box just as Joe Higgs drove his truck to their door and tooted his horn.

"That glue won't dry, Jo Ann, Wicky said warningly.

"It's got to dry!" said Jo Ann. "If it can't be dried any other way, I'll do it with my electric iron."

Wicky was now standing in the box.

"Sit down," said Jo Ann, and Wicky sat down, or tried to.

"I can't sit down, Jo Ann," Wicky said. "I'm too wide, and it's too narrow."

"You've got to sit down!" Jo Ann cried, and Wicky tried to sit down, but there was no hope. She was not built at all like a radio cabinet. Jo Ann shook her fists up and down in disappointment and irritation.

"Get out!" she ordered. "Get out! You'll never do; I've got to get in it myself," but she had to help Wicky get out, pushing the box off her. Joe Higgs was tooting his horn to hurry them, and Jo Ann dashed for the closet and got into her gym clothes.

"Hold the box, Wicky," she said breathlessly. "It's a good thing I'm narrow, anyway. You ought to reduce."

She stepped into the box and settled down in it. Joe Higgs was honking his horn steadily now.

"Hurry up, up there!" he called.

"Yes! In a minute!" Jo Ann screamed.

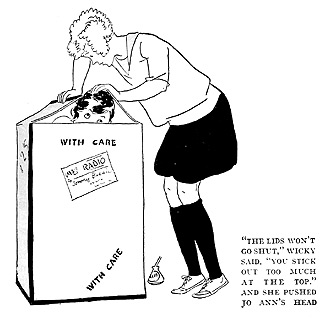

"The lids won't go shut," Wicky said. "You stick out too much at the top."

She pushed the top of Jo Ann's head, but it was no use. Jo Ann could not be compressed.

"The pillow," said Jo Ann, and she reached down to pull out the pillow, thinking it might make more room in the box, but she exclaimed "Oh!" in something very much like anger, for her feet went straight through the bottom of the box.

"That settles it!" she cried, pulling the box off over her head and throwing it at the bed, where it flattened out, as such boxes do when their ends are open. "I could cry!" she said. "I could scream and yell!"

"It's too bad!" said Wicky, but she was glad she was not a thin little slip of a thing that would have fitted into the box. "Couldn't we write 'April Fool' on a piece of paper and -- Jo Ann, we ought to have a parrot!"

"Honk-honk -- Honk-honk-honk!" honked Joe Higgs outside.

Jo Ann ran to the window.

"Stop that, can't you?" she demanded. "Go away! I mean, we don't want you."

"All right, lady," said Joe Higgs. "You're the boss."

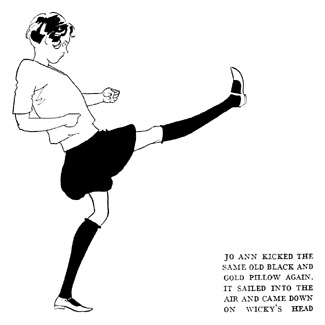

They heard the truck jolting away and Jo Ann turned to the room again. There was nothing to kick but the same old black and gold pillow, so she kicked that.

"What did you mean about a parrot?" Jo Ann asked.

"I just thought," said the patient Wicky, "if we had had a parrot and had taught it to say 'April Fool!' we might have put the parrot in the box, and when Tommy Bassick opened the box --"

"He'd have had the parrot," said Jo Ann.

"Well, yes," Wicky admitted. "But if it was a parrot we didn't want -- if it was a parrot we wanted to get rid of, Jo Ann --"

"Oh, don't be silly!" said Jo Ann. "If I had a parrot, I'd keep it. If it was a parrot I wanted to get rid of, I'd have gotten rid of it long ago."

"Well, the glue wouldn't have stuck, anyway," said Wicky.

"No," said Jo Ann with a deep sigh. "No, I guess not. It would have been wet, and he would have known it was an April Fool."

"Unless I dried it with your electric iron," said Wicky.

"You don't think I'd let you iron right on top of my head with a hot iron, do you?" Jo Ann demanded.

Wicky did not say anything to this, for as she was reflecting sadly, someone tapped on the door.

"If you please," said the matron when Jo Ann opened the door, "a large box has just come for you, Miss Jo Ann. Do you want it brought up here?"

"A large box?" Jo Ann asked, suddenly suspicious. "No; we'll go down and look at it, Mrs. Cullihan."

She hastily buttoned the buttons she had unbottoned, and, with Wicky, went down. The box was just such another box as the one in Jo Ann's room, and she looked at the label. It was addressed to Thomas Bassick, Spenceville Academy, but not with a radio shop label, and across the top, with a heavy blue pencil, Tommy Bassick had scrawled, "April Fool yourself -- Tommy Bassick."

Jo Ann, using her clasp-knife, slit the linen strip and opened up the two lids of the top of the box. In the box was another cabinet radio set exactly like Jo Ann's own.

Some four days later Jo Ann was called to the telephone and found that Mr. Bassick -- Tommy's father -- was on the long distance wire. He was asking about a radio set he had sent Tommy, and he laughed a great deal.

"Why, yes, Mr. Bassick," Jo Ann said. "It's here; I've got it; Tommy sent it to me, you know, but, of course, he can have it if he wants it. But, Mr. Bassick, he'll have to come for it."

"You're a terror, Jo Ann." Mr. Bassick laughed. "All right; I'll tell him," and the next day when Tommy came with Joe Higgs, Jo Ann and Wicky leaned out of their window, watching the loading of the box.

"April Fool, Tommy!" Jo Ann called down to him sweetly, and then she whispered to Wicky, "It's a good thing you didn't go in a box, Wicky," she said; "he'd have sent you back unopened," and then both girls giggled and Tommy got beet-red in the face and kept his red head low. The joke was on him.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 2:42:00am USA Central