|

|

from American Girl

The Stolen Mascot

by Ellis Parker ButlerIt was after five o'clock when Betty Bliss and Dot Carver and I got as far home as Betty's yard, and we went around to the lawn back of the house and sat down on the grass there. We were tired, but Betty said we really must have a meeting of our Detective Club because we were supposed to have one every Thursday, and this was Thursday.

"But, Betty," I said, "let's not bother today. Nothing has happened. What's the use of having a meeting?"

"Now, Madge!" Betty said. "Please! What if nothing has happened? You can't expect a crime every week in a town like Westcote, but if the Detective Club doesn't meet, we will forget we are a detective club, and then we won't be ready when a crime does happen. Inspector Carver, have you anything to report?"

"Not a thing, Betty," said Dot, but she saw Betty frown. "I mean," she corrected herself, "there's nothing to report, Superintendent Bliss."

I hadn't anything to report either.

"Nothing except that my legs are tired, and oh my feet!" I said. And that was the truth because this was the third day of the Westcote Old Home Week, and we three girls were peanut sellers for the Associated Charities booth, and had we been busy!

The Old Home Week was held every five years. It was a great affair, with booths of all kinds, and men selling toy balloons and horns and flags, and over forty different street shows. Everyone said this was the best that Westcote had ever had, and we three girls were certainly having a lot of fun. Betty Bliss was holding a teddy bear she had won at the ring-tossing game, and I had a big box of bath powder I had won throwing rubber balls into tin basins. Dot, poor child, had not won anything, although she had spent all of twenty-five cents at one of those Japanese ball rolling places. I offered her my bath powder for five cents, but she took one whiff and said "Nay!" I did not blame her. It smelled awful.

"Well, let's adjourn," I said, meaning the meeting of the Detective Club. Betty Bliss said we might as well, but before we could scare up enough energy to get up off the grass, Dick Prince and Billy Waters came strolling around the house. Dick had a cane with an Old Home Week flag on it.

"See what I won," he said. "What's this, a meeting of the famous Betty Bliss Detective Club? We're not butting in, are we?"

"We're just through," Betty said.

"Where did you get the teddy bear?" Billy Waters asked. "Win it? What are you going to do with it?"

Betty bent the teddy's legs and made it sit up on her hand. It was a small teddy, no bigger than a kitten, and fuzzy and soft.

"I won it, and it is going to be the mascot of the Detective Club," Betty said. "We'll call it Sherlock Holmes."

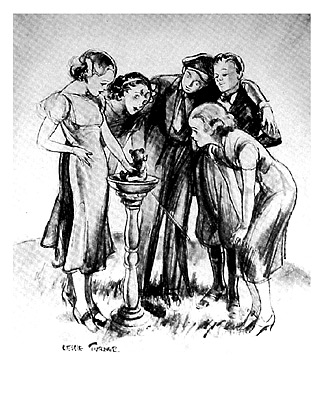

She got up and walked to the birdbath that stood in a circle of close-cropped lawn. The birdbath was as dry as a bone, because Silas, the colored man-of-all-work for the block, was supposed to keep water in it, but he never did. It was just an ordinary birdbath, like a circular shallow dish on a three-foot pedestal, and Betty plumped Sherlock Holmes down in the dish.

"There, Sherly," she said. "You sit there. Work your charms. Do your miracles. Be a good little mascot and bring us a nice harmless crime to solve."

"He will," laughed Dick Prince. "He will if you leave him there, Betty. Somebody will come along and steal him, and then you can sing 'Sherly! Sherly! Who's got Sherly?'"

"You mean you're going to steal him, Dick Prince?" demanded Betty. "Is that what you mean?"

"If I do," Dick laughed, "you won't know I did it, and you won't know how I did it. It will be one of those unsolved crimes. 'Detective Betty Bliss Baffled; Detective Club Finds No Clues.'"

"Really!" Betty scoffed. "Well, listen, Dick -- I may be only a simple female, but I dare you to steal our mascot in a way I can't guess."

"Go to it, Dick," Billy Waters urged. "Be a gentleman thief for the lady. Give her a crime she can't possibly solve."

Dick looked at the teddy bear in the birdbath and grinned.

"It's hardly fair," he said, but I could see he was eager to try to outwit Betty. "She's had warning. She'll know I took the mascot."

"Now, that's only partly so," I declared. "If we leave the teddy there, Dick, anyone might take it. Any kid that came into the yard might pick it up. I might take it to confuse Betty. Or Dot might. And you said she wouldn't know how you stole it."

"Well," said Dick, still grinning, "she wouldn't. Not unless she sits by the teddy all night and watches. I'll have a try at it. You'd better kiss your mascot good-bye, Betty."

"Good-bye, mascot," Betty laughed, throwing a kiss at the teddy, and Dick and Billy laughed. They went off to one side a little and whispered to each other, and then walked slowly around the circle on which the birdbath stood, looking at the teddy from all sides. The circle of lawn was about twenty feet across, and the driveway that led to the garage went on all sides of it. It was a gravel driveway and the gravel was loose. Silas did keep it raked and smooth.

"The villains study the scene of their proposed crime," Dick called to us from the far side of the circle, and then he waved his hand at us, and he and Billy left us. Dick went straight into his own yard, which was right next door on that side with only a few trees between and no fence, and Billy crossed Betty's yard below the birdbath circle. He lived on the opposite side from Dick.

We sat a little while longer, discussing Dick and Billy and the proposed theft of our mascot, but Betty said there was no use at all in guessing at their plans in advance.

"No one can tell how a crime is going to be done," she said. "Dick and Billy may be thinking of one way now, and they may change their plans half a dozen times before they try to take Sherlock from the birdbath. But, Madge --"

"Yes, Betty?" I asked.

"You don't want that awful smelly bath powder, do you?"

"I surely don't," I told Betty. "Do you?"

"I could use it," Betty said, getting to her feet, and I handed her the box. She tore it open. "This will not protect Sherlock," she said as she began sprinkling the bath powder on the circular lawn around the birdbath, "but it may give us a clue after he is gone. This powder ought to show where the thieves have stepped, and some of it ought to cling to their shoes. If they cross the lawn on either side of the driveway some of the powder should show on the clean grass there, and tell us which way the thieves have gone."

"Clever!" Dot exclaimed.

I do think of things once in a while," Betty smiled, and she handed me the empty box. The grass around the birdbath now looked as if it had frost on it, and it was sure to show where anyone stepped, and Betty said so. "Unless," she added, "they use stilts, and even stilts would make some sort of marks."

With that we said good night, and Dot and I went home. I wanted my dinner and a good bath and my bed. We had to sell peanuts for the Associated Charities booth again the next day, and my feet were wrecks.

The next morning as soon as I had eaten my breakfast I went over to Betty Bliss's, and the teddy mascot was still sitting in the birdbath, and Betty and Dot were waiting for me. We had another strenuous peanut day and again, when we got back to Betty's house, the mascot was just as we had left it. But there were clear and unmistakable footprints in the bath powder of the circle. They led directly from the Bliss's kitchen door and back again.

"They're Delia's," said Betty immediately. "I can read that plainly enough. I should have told her to keep off. Delia has seen the teddy in the birdbath and she has wondered what it was, and she has come to see. She would, of course; she must have wondered what queer sort of bird or squirrel was plopped down there, never moving. I would have wondered the same if I had been Delia. The only surprising thing is that she did not take teddy into the house."

"And then we would have had a fine time discovering who took him," I remarked.

"Why, no, Madge," Betty said. "Not at all. I knew Delia had been to the birdbath, didn't I? And the first thing Delia would say when I went into the house would be, 'Miss Betty, is it your teddy bear I found out there in the birdbath?' That would be easy, Madge."

And, sure enough, just then Delia did open the kitchen door and she asked, "Is that your teddy bear in the birdbath, Miss Betty? Sure, an' I was puzzled t' know what it was at all!" so Betty had to explain why we were leaving the teddy where it was.

"Well, girls," said Betty, "tonight is the night, I expect, and do you know what I'm going to do? I'm going to invite myself over to Madge's for the night -- is that all right with you, Madge? Because I don't want Dick Prince to be saying I peeked."

"Fair enough, Superintendent Bliss," I laughed. "And you are invited, too, Dot. We won't have Dick and Billy saying we spied on them; my father and mother will be our witnesses that we did not."

We had seen nothing of Dick or Billy that day, and we saw nothing of them now. Betty came to my house immediately after dinner, and Dot came half an hour later.

"There is only one thing that annoys me," Betty said when we were all in my room, "and that is that Delia tramped across that circle with her none too small feet. If the boys were there today making observations, they must have seen those tracks, and they make a lovely path for them. They can walk in Delia's footprints."

"And how will you prove that Dick and Billy took teddy if they do that, Superintendent?" I asked.

"That is a bridge we will cross when we come to it, Inspector," Betty said. "Let's forget the case until morning. Have you anything good we can read, Madge?"

I had a mystery story my father had read and told me I could read -- The Mystery of the Blue Orchid -- and we took off our shoes and made ourselves comfortable, and took turns reading until we were sleepy. I looked out just before I went to bed, and I saw it was a beautiful night with a bright moon -- just the night for the crime. I slept like a log, not even one dream, and I don't mind saying that I was excited when I awoke. I know Betty was. Even before she had breakfast, she telephoned home.

"Mother," she said, "would you mind looking out of a window and seeing if my teddy bear, the little one I got at the street fair, is in the birdbath? Don't go out; just look from the window, please."

There was no teddy bear in the birdbath, Mrs. Bliss said. You can guess whether we hurried through breakfast! I think I never rushed through a meal as I did through that one, and Betty and Dot were not a sip or a bite behind me. We hurried over to Betty's house, and fairly ran to the rear lawn and to the birdbath circle.

"Keep back! Don't go on the grass!" Betty warned, and we stopped short. "Just follow me," she said, and she walked around the circle, keeping on the gravel of the driveway and not taking her eyes from it.

"Nothing!" she said when she had returned to our starting point. "If anyone walked on the gravel there are no traces of it. Now for the grass."

We walked around the circle again, this time looking at the grass. Delia's footprints showed plainly enough, but there were no other footprints in the bath powder. No one had walked across to the birdbath, and the teddy was gone. "No need to be careful now," Betty said. "Only don't walk in Delia's footprints -- I may want to examine them more carefully. If the boys used them, they may have made extra prints somewhere, not stepping exactly in them. See if you can find marks of stilts, Inspectors."

We searched carefully, but there were no holes such as stilts make, and Betty walked to the birdbath.

"Girls, look here!" she cried, forgetting to call us Inspectors in her excitement. "Come here!"

Dot and I hurried to the birdbath, and Betty put out a hand to keep us back.

"What is it?" I asked. "I don't see anything."

"You don't? Do you, Inspector Carver?" Betty asked Dot.

"No," Dot said. "What do you see, Betty?"

"'Superintendent,' please, when we are on a case," Betty said. "Look again, Inspectors. Don't you see there is water in the birdbath?"

Well, of course, there was a little water in it, and that is what you would expect in a birdbath. But I remembered now that the bath had been dry when Betty put the teddy mascot in it.

"Probably Silas has been around and put water in it," I suggested, for that certainly seemed to be the most natural explanation.

"Probably he hasn't!" scoffed Betty. "In the first place, good old Silas never got on a job as early as this in his life; and in the second place, Madge, when Silas fills the birdbath, he fills it full to running over. Always. And there is only a cup or so of water in it now. What do you make of that, Inspectors?"

"You mean that the boys put the water in the birdbath?"

"Who else? Who would bother to put just one single cupful of water in it, and no more?"

"Why would they put any in it?" Dot asked. "Was it a smarty trick to show us they had been here?"

"Billy's name is Waters," said Betty thoughtfully. "It may mean that he was giving us a clue -- leaving a sort of sign manual. But that would be silly. If he did that, just to tease us, Dick Prince should have left one, and he didn't."

"Prince -- prints," I said. "Footprints, Betty. Prince and Waters -- prints and water, how's that?"

"They're Delia's footprints, not Dick's, so far as we know now," Betty said, and looked thoughtful. "No, this water means something else, but I can't imagine what. Why should they leave water in the birdbath, Madge?"

"You tell me, Superintendent," I said. "I can't tell you."

"Water," said Betty, and she shook her head. "I know it means something, if I could only guess it." Suddenly she brightened. "Look here!" she cried, and she pointed to the edge of the birdbath. Dot and I crowded forward and looked where Betty was pointing, and what we saw was a tiny place where a bit of the edge of the birdbath had been chipped off. It had been a chip no larger than the nail of my little finger, if that large, and it would not have meant a thing to me, but Betty seemed to think it was a wonderful find. She turned and looked up at a window in Dick Prince's house, and then turned and looked the other way, and strode across the circular grass plot and across the gravel drive on the side toward Billy Waters's house.

"What is it, Betty?" I asked, hurrying after her, but she was down on her knees beside a bed of tulips, and I saw that one of the tulips was bent down, its stem broken short.

"Don't touch it!" Betty ordered. "Don't step near it. I'm beginning to see, Madge. Old Home Week, of course!"

"Old Home Week?" I cried. "Whatever do you mean, Betty?" And Betty was so busy she did not object because I did not call her "Superintendent." She was pawing in the soil around the broken tulip as if her fingers were a rake.

"It ought to be here," she said. "I know it is here somewhere."

"The teddy bear?" I asked. I hadn't the slightest idea what she meant, unless it was that the boys had buried the teddy there, but suddenly Betty exclaimed "Ah!" and straightened up.

She held up something between her thumb and forefinger, and at first I thought it was a pea.

"A BB shot," she said. "The kind Dick Prince uses in his air rifle. So now I guess you know how they stole our mascot, and this proves that Dick had a hand in the theft."

"I don't see how," I said, and then I added, "Superintendent." Betty laughed.

"Get down here, Inspector Madge," she said, getting up, "and look across the top of the birdbath where the nick is, and tell me what you see -- the farthest thing your eye does see."

"I see Dick Prince's window," I said. "You mean he shot his air rifle from his window?"

I certainly do mean that," Betty said. "And if I hunted enough, I'd probably find several more BB bullets, for Dick is no such shot as to hit his mark the first time. And now, Inspectors, turn your heads and tell me what you see that is a direct line from Dick's window. Where would a string go, if it was stretched straight across from Dick's window, over the birdbath? Look along that line -- and what would you see?"

"I would see Billy Waters's window," Dot said.

"Certainly," Betty said. "A string stretched from Dick's window to Billy's window would be exactly over the birdbath. Girls, I'm afraid we will never see our teddy mascot again."

"Why not? What do you mean?"

"I mean," Betty said, "our teddy has gone for an air voyage. I mean that our mascot has gone sailing into the sky. 'Up in a balloon, boys, sailing 'round the moon,' if you know what I mean."

"I don't know what you mean," I said, and just then Dot cried, "Here come the boys now," and we saw them coming around the house. Both of them were grinning as if they were saying, "Well, I guess we fooled you this time," and that is exactly what Dick did say.

"Well, almost," Betty said. "Of course, I knew you would try some way that would be unusual, but I did not think of balloons until I saw where the BB shot had chipped the birdbath."

Dick's mouth fell open.

"They peeked," accused Billy Waters. "They watched us."

"We did not!" I declared. "We were all over at my house all night. I don't know myself how Betty thought it out. I don't know what she means about balloons. Tell us, Betty."

"What the boys did was this," Betty said, and she did sound like a detective in a book. "They were careful not to step on the powder we sprinkled around the birdbath, and they decided to steal the teddy in a way we could not guess. I knew that, of course, and I tried to think how I would go about it if I were in their place. Some way, you understand, that would leave no footprints. So it would have to be from the air, you see."

"Smart girl," said Dick.

"Don't be fresh," said Betty, but she smiled. "Of course, I thought of balloons, but I did not think they had used balloons until I saw the chipped place, and the water in the bird hath. And then the broken tulip proved that Dick had shot and missed once or twice. You remember I said 'Old Home Week,' Madge?"

"Yes, but I didn't know what you meant by it."

"You could hardly buy toy balloons filled with gas in Westcote except when there was some sort of festival in town. I suppose that seeing the balloons being peddled suggested the plan to Dick -- or to Billy -- so they bought a bunch of them to carry our teddy away. The only difficulty was to devise a way to make the balloons steal the teddy. They did that by fastening fishhooks below the balloons."

"But gas balloons go up," I said. How --"

"How did they get them to come down to the birdbath and pick up teddy? Quite easily," said Betty. "They stretched a cord from window to window and drew the balloons across until the hooks were exactly over our teddy. They weighted the balloons by hanging to them an extra balloon with water in it -- balanced the upward pull of the balloons with just enough water. Then, when they had hooked teddy, Dick shot at the water-filled balloon and burst it, and up the balloons sailed. One of the boys let go his end of the string, and the other pulled the string loose from the balloons. Am I right, Dick?"

Dick laughed, and then he put out his hand and shook Betty's with mock seriousness.

"Superintendent Bliss," he said, "you win. There's only one thing you haven't guessed. Pardon me, I mean there is only one thing your amazing detective acumen has not been able to tell us."

For a moment Betty looked a bit chagrined.

"What was that?" she demanded, and again Dick laughed.

"The colors of the balloons," he said. And then Betty laughed, too, for nobody could have said in a nicer way that he thought Betty was too smart for him.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 2:31:20am USA Central