from Century Magazine

The Day on the Roof

by Ellis Parker Butler

It was a grand temper that old Dan Reilly had. He brought it with him from Ireland when he was yet a young man, and he kept it in good condition by this means and that through forty years of hod-carrying, so that when he came to be sixty-two and owned his own little house and lot and had money in the savings bank, it was still a strong, serviceable temper, ready to flare up at need.

His temper was like strong drink to Dan Reilly, and in temper he was no prohibitionist, nor even a temperance man. Seldom the day that he did not have his little spree of hot anger.

He was a fine old man, was Dan Reilly, and raised a dozen freckled children, one of whom he lived to see behind the bar of his own saloon, and boss of the ward in politics. Dan was none of your grumpy fellows who chew the cud of sulkiness and spit out sour words, but a red-headed, red-hot Irishman, and his temper was like a gunpowder explosion, and his words came forth hot and glowing when he had the fit upon him.

A man has rights in these free United States of America, -- oceans of rights, if he but knows them, -- and he is a poor fellow who does not have most of them trampled upon these days. Whatever does an Irishman come all the way across the water for, then, and swear to uphold the Constitution and By-laws of the United States for, if, by all the saints, he is going to let every one walk all over him and his rights? No wonder a man gets mad now and again. Looking at it fairly, Dan Reilly seemed to have more rights and more people stepping on them than any other man in the city. And a grand temper the little man produced out of the wrangles.

Hard on him was it to have the neighbors he had, too. It would throw any man in a temper to have neighbors who would never get in a temper, and that was the trouble with Van Dusen, to the left of Reilly, and Umholt, to his right. What are neighbors for if they can't get in a sociable quarrel now and again?

There was Umholt. the tailor, now. He sat cross-legged on his long table at the window of his cottage, pulling his thread before his weak eyes all day, with never a smell of excitement, and yet in the tail of the day, when he came into his garden, never a quarrel would he have, or a hot word, or a fierce look. It was unneighborly.

"Oi do be thinkin' thim Dutch hev no blood in thim at all," said Dan to his wife, one morning after his pig had spent a voracious night in the Umholt garden. "Niver a worrud did ould Umholt say whin he druv the pig home, an' half his cabbages gawn. Uf his pig ate up my cabbages Oi'd l'ave him hev a bit av me moind, now, Oi w'u'd. Phwat roight has a man to be havin' his pigs go roamin' around devourin' up people's green truck, Oi'd loike t' know? Bliss his sowl, Oi'll show him! The idee! Is ut t' fat his pig Oi do be worrukin' me arms aff all the spring? Oi'll hev the law on him, Oi will!"

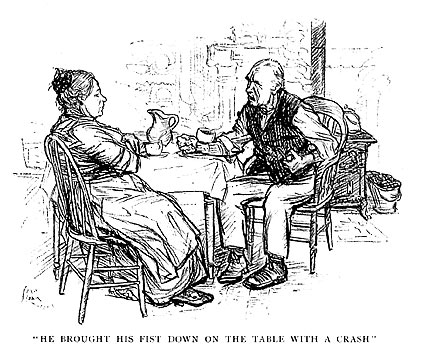

He brought his fist down on the table with a crash that made the dishes rattle. Mrs. Reilly settled her two hundred and odd pounds comfortably back in her chair and folded her arms. She had grown fat and cheerful on forty years of Dan Reilly's temper.

"Talk sinse, Dan Reilly," she said. "No pig aloive c'u'd git out av Umholt's sty, an' ye know ut. Ut's yersilf moight betther be patchin' up yer own sty to kape the pig insoide, than to be blissin' ould Umholt, the poor droied-up felly. Ut's a good man he is, uf he do be Dutch, an' ut's him moight betther be blissin' ye an' yer pig. Wan w'u'd think 't was his pig got intil yer cabbages, to hear ye go on."

Dan shook his fist.

"Oi'd loike to see his pig in me lot, Oi w'u'd! " he cried. "An' Oi'd loike to see him hev worruds wid me beca'se me pig made free to break out av the sty! Sue me, w'u'd he? Jist let him thry ut, the ould, droied-up tailorman. Oi'll show him an Irishman has as good a roight to kape a pig as a Dutchman has!"

He shook his fist savagely. He was so angry he could not hold his hand steady enough to light his pipe.

"Him!" he cried. "Him! Oi'll show him yit, Oi will, the tame ould burrud that he is! Oi hev me roights!"

He crushed his soft hat upon his head and went out on the porch, where he sat on a step and glared at the inoffensive tailor, who was sewing away in his open window.

The Umholt cottage was close against the dividing fence, and there was room for only a narrow footwalk between the same fence and the Reilly cottage, so Dan had a good view of the tailor. The tailor nodded a lifeless "Good morning," to which Reilly paid no heed whatever.

Umholt was a tall, thin man with eyes that were sheep-like in their gentleness. Years had dried his skin to a wrinkled parchment, and a worthless son had sobered his heart. If he had not been so industrious he would have been a weak man, and if he had had a little more blood he would have been an individual; as it was, he was nothing and nobody. He was only tailor Umholt. It provoked Dan Reilly to see a man so meek and lowly.

"The pig had a gay time in yer garden the noight," he said tauntingly.

"It did small harm," said Umholt, listlessly.

"They'll be a short crop av sauer-kraut near by," Dan taunted.

The tailor shifted the trousers on which he was sewing and continued to sew. He clipped his thread, rethreaded the needle, and again bent his back into a curve over his work.

Reilly cast his eye abroad to find something on which he could hang his anger. The division-fence still had a picket missing, but that was his own affair. The lilac bush in the tailor's yard was so trimmed that not a leaf extended beyond the fence. A few bits of washing were hung on the fence, but they were the Reilly washing, and therefore inoffensive. Then Dan's eyes rose to the eaves of the Umholt collage. They were broad eaves, extending well beyond the walls of the cottage, in striking contrast to the eaves of the Reilly mansion. The one roof resembled a broad-brimmed hat, the other a brimless skullcap.

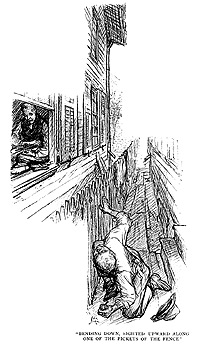

Dan Reilly descended from his porch, and bending down, sighted upward along one of the pickets of the fence. The Umholt eaves did not project the sixteenth of an inch beyond the line. Dan tried another picket, and, glory be! The eaves did encroach on his territory, according to that picket, a full inch or more.

"Umholt," he shouted, "the roof av yer house sticks over beyant me fince, ut does!"

Umholt raised his eyes listlessly.

"Mebby so," he said. "Mebby the fence is wrong. I didn't build the house. I didn't build the fence. What difference makes it?"

"Whut difference, indade!" fumed Dan Reilly. "Ut's threspassin' ye are, wid yer roof stickin' all over me propputy, shuttin' out me loight an' me air, an' you a-settin' there, grand as a king, sayin', 'Whut difference!' Belike the fince is wrong, Umholt; belike ut belongs a foot yer way -- Oi dunno. An' you, so meek, a-livin' on me roightful propputy these twinty year gawn! Shmall wonder ye sit there so quiet an' saint-loike, ye ould thief, knowin' ye've been kapin' me roights from me these twinty year an' laffin' behint yer face at me! Oi'll hev the law on ye, Umholt, or me name's not Dan Reilly!"

It as a sad fact that the early surveyors of the town were careless or inefficient. True, the town had once been a succession of hills and hollows, and land had been too cheap to quarrel over; but, with growth and grading, property had become valuable and surveying more exact, and with the movement for paved streets had come a correction of long-standing errors in boundaries. There was Morgan, who had had three feet of his lot taken from him and added to the public thoroughfare; and Wilkins, on the opposite side of the street, who had been presented with three feet; and many others. The surveyors had found that some blocks, which were supposed to be three hundred feet, contained three hundred and ten, while others had a scant two hundred and ninety. But the paving had not come Reilly's way, and the boundaries on his block had remained unchanged.

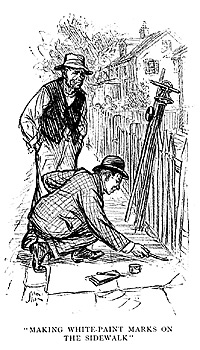

However, the next day Dan Reilly sought out a surveyor. He was not a full-fledged surveyor, but he had the little telescope on stilts and the stick with the red-and-white disk, and he did well enough for the purposes of a man in a passion. He began at the far end of the block, and approached the Umholt cottage slowly, making white paint marks on the sidewalk as he proceeded, and when he made the last, it was two feet beyond Dan Reilly's fence and close against the Umholt wall.

It was a triumphant moment for Dan Reilly. Although the tailor still sat at his open window, Reilly formally entered the Umholt yard by way of the front gate, and rang the doorbell. When the tailor opened the door the conversation was short.

"Oi wish to give notice, Misther Umholt," said Dan, triumphantly, "that the surveyor has tuk a squint at the block, an' yer roof is two fate on me propputy."

The tailor, holding an unfinished garment in his hand, pushed his spectacles up on his brow, and gazed at Reilly with his weak blue eyes.

"So?" he said mildly, as if neither this nor aught else could greatly surprise him.

"Oi'll thank ye to move back the house," said Reilly.

"Yes," said the tailor, "dot iss right. So soon as I get some money I move him."

Reilly was disgusted. There was no light in this tailorman.

"Uf ye loike," he suggested, "ye kin hev yer own surveyor thry his hand at ut. They do make mistakes sometimes."

The tailor would not even accept this opportunity to make a pretty quarrel of it.

"It makes no difference," he said carelessly. "Two feet, what's that? Mebby the house isn't so damp if I put him by the middle of the lot. I move him so soon as I get some money."

Reilly blazed into vivid anger.

"Oh, yis!" he cried, "ut's the proud, unsociable temper av yez, wantin' to git farther away from yer neighbors. Dom the Dutch, annyhow, always thinkin' thimsilves betther than their betthers! Good riddance if ye moved clane aff the block, Misther Umholt! But move near or move far ye must, for Oi've stood yer threspassin' long enough. Oi give ye fair warnin' to git the roof aff av me propputy this noight week, or Oi'll take ut aff mesilf."

The tailor waited until Reilly had turned his angry face and had walked to the gate, and then he closed the door gently and went back to his work.

The succeeding week was one of vivid emotion for Reilly. The tailor made no sign that he intended moving his cottage. Reilly, in his heart, hoped he would not, but he was gloriously angry because he did not.

In the meantime Mrs. Reilly and Mrs. Umholt talked the matter over amicably across the fence which separated their back gardens, and which was soon to absorb two feet of the Umholt property.

"Dan do be an ould fool, Mis' Umholt," said Mrs. Reilly, " but the saints in hivin can't move him whin he's got the anger on him. But, shure, that's no rayson fer hard feelin's bechoon fri'nds."

"Not at all, Meesus Reilly," said Mrs. Umholt. "I haf many times to Umholt said, 'Bernard, I wish you haf more spirit, like Mister Reilly, then we git ahead faster,' We won't haf no fights mit sich foolishness, Meesus Reilly. Und, anyhow, if the land to Reilly belongs, it is hissn." Mrs. Reilly sighed.

"Ye spake loike a loidy, as ye are, Mis' Umholt," she said, "an' Oi hope ye'll pick thim cabbages afore Dan moves the fince over, Oi do."

"Ach now!" exclaimed Mrs. Umholt, "und what for should I take the cabbages? To make Mister Reilly mad some more? When the ground is hissn, the cabbages is hissn, no?"

She laughed good-naturedly, and Mrs. Reilly laughed, and they both looked where Dan Reilly sat on his side porch, with his elbows on his knees and his chin in his hands, scowling at the tailor, and they laughed again.

The allotted week passed, and on the threatened day the sun arose, hot and glaring; but Dan Reilly arose earlier and hotter. By the time the east was first tinged with light he was seated astride the ridgepole of his roof. Beside him lay a ladder, a saw, and a shotgun. In his pocket were a chalk line and a fool-rule. In his heart was fury. Since the tailor had not moved the house, Dan Reilly proposed to remove two feet of the offending eaves, and if Umholt interfered -- well, the shotgun was loaded.

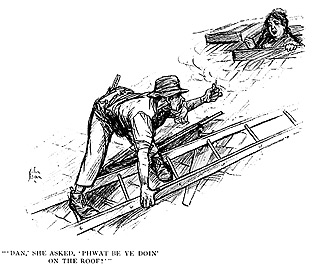

At this early hour Dan Reilly had the world pretty much to himself, even in that early-rising part of the town, and as he moved carefully about on his shingles in his stocking feet he made little noise; but when he began moving the ladder to the edge of his roof, the noise awoke Mrs. Reilly, and she hastily slipped on her wrapper and stuck her head out of the trapdoor of the roof.

"Dan," she asked, "phwat be ye doin' on the roof?"

"Gwan down," said he, "an' tind yer own business."

"Is the house afire?" she asked, with more alarm.

Dan was holding to the roof with his hands and feet, and at the same time trying to smoke his pipe and move the ladder, and his irascibility was great.

"Gwan down!" he cried. "Gwan down! Git down! Don't sthand there wid yer head stickin' up loike an avil janius! Or do yez want me to come over an' crack ye wan?"

"Ye'll fall aff the roof, Dan Reilly," said Mrs. Reilly, warningly.

"Oi will uf Oi want to," shouted Dan,"an' don't thry to sthop me uf ye don't want trouble. Gwan down, now, afore Oi kim up an' make ye!"

Mrs. Reilly shrugged her plump shoulders and withdrew her head, only to appear a minute later in the yard below, while Dan kneeled on the roof and let his anger bubble over in mutterings.

He moved the ladder toward the edge of the roof, and then carefully raised it on end. A moment it stood upright, and then he allowed it to fall toward the Umholt cottage. It fell with a great clatter, striking the edge of the Umholt eaves, and then rebounded into the yard below, where it hung half suspended from the fence. Dan clung to the roof like a cat on a clothesline. The noise awakened the Umholt family, and before Dan had removed the ladder from the pickets Mr. and Mrs. Umholt issued from their kitchen dour.

"Ut's on'y Dan," volunteered Mrs. Reilly, reassuringly; "he be on'y goin' to cut aff a bit av yer roof, loike."

"Dot's all right," said Mrs. Umholt; "dot's sheeper as to move der house, ain'dt it?" But Umholt merely stood and watched Dan Reilly with impersonal curiosity.

When Dan had righted the ladder, with an accompaniment of harsh words and grumbling, and had placed it against his own roof again, Mrs. Umholt ventured a suggestion.

"It's easier ven he cooms by my door in und goes up the stairs like, ain'dt it?" she asked. "Mr. Reilly," she called, "coom by my house in. Mebby you don'dt fall mit der ladder down so. Ve don'dt hurt you."

"Hurrut me!" yelled Dan. "Oi'd loike t' see yez hurrut me, or sthop me, ayther. Divil a bit do Oi go in the house av yez, to be havin' yez after me fer threspass! Jist thry to sthop me wance!"

"Ut's himsilf is the bould man the mornin'," said Mrs. Reilly soothingly to Mrs. Umholt. "The divil himsilf couldn't sthop him whin he's set thot way."

"I don'dt vant he should hurt hisself, dot iss all," replied Mrs. Umholt. "Such an oldt man to be climbin' latters!"

But the old man had climbed many ladders in his day, and with heavy hods of brick to ballast his back, and he was soon on the roof again, preparing for another cast of the ladder.

"Ven he t'rows dot latter once more, mebby he preaks a vindow, no?" asked Mrs. Umholt. "Mebby I bring der clothespole und helps him."

She did so. At least, she got the long clothespole and explained to Reilly that if he would slide the ladder out from his roof she would support the end until it rested upon her caves. She explained this in a soothing tone, while Dan Reilly supported the ladder in an upright position. When she had explained in full, he motioned her away.

"Gwan away," he said shortly. "Oi'm goin' to dhrop ut. Uf yez don't want yer head cracked, gwan away!"

The ladder fell in a clean quarter-circle and struck the Umholt roof sharp and fair. It bounced slightly, but did not fall, and when Dan had straightened it a bit he gathered up his saw and gun and crossed the gulf on his hands and knees.

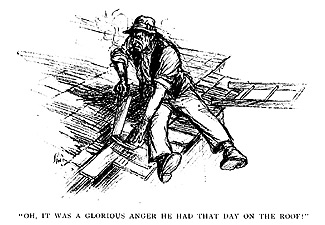

The town was awakening, and one by one small boys and girls began to gather at the street fence, and they were joined now and then by men on their way to work. But Dan paid them no attention. Clinging like a squirrel to the two feet of eaves that were on his property, he stretched his chalk line and snapped the white mark for his saw to follow. His wife and Mrs. Umholt urged him to get farther upon the roof, but he ignored their prayers. Not an inch would he trespass on the Umholt line.

Then he began to saw. He began at the rear end of the roof. The day was hot, and his position insecure. His saw was a cross-cut, and the boards of the roof beneath the shingles were with the grain. As he reached each shingle it flapped up and down or stuttered against the teeth of the saw, and he had to hold it flat with his hand. Every minute or two he struck a nail, and it did not need the harsh rasp of steel to tell those below that the saw was in trouble. Dan Reilly told them.

Oh, it was a glorious anger he had that day on the roof! He had his full of it. He was mad at the sun, at the dulled saw, at the nails, at the loose shingles, at his wife for chatting with Mrs. Umholt, at Mrs. Umholt for remaining placid, and, as the day wore on, he became mad at the children in the street. But, above all, he boiled with rage at Umholt, who stood calmly watching the curtailment of his roof. Umholt was interested, but merely as a curious spectator.

It was a long, hard day for Dan Reilly. He was not the strong young fellow he had once been, and by suppertime he ached well; but his anger still held out, and in the late twilight he continued sawing through pine shingles and steel nails. Then came darkness, and he lighted a lantern and went on with the work; but Mrs. Reilly went inside to attend to her neglected duties, and Umholt went in and went to bed, and a few moments later Mrs. Umholt said "Goot nacht" and followed her husband.

At eleven o'clock Dan Reilly had left only enough of the trespassing eaves to sit upon, and if he sawed that off he would drop with it. He peered down and saw the sharp pickets just below. He decided that it was hardly worth risking. On the whole, the day had been a failure. Umholt had not angered worth a penny. There was no fight in the man. But, on the other hand, Reilly had had a glorious rage. Even the meekness of Umholt had helped him there. And as he sat in the lantern light on the roof a great plan came to him. He chuckled as he thought of it. Tomorrow he would take his shotgun and make Umholt saw off those hist two feet of the eaves. He chuckled as he imagined the lanky tailor sitting cross-legged on the roof. He chuckled as he climbed across the ladder to his own roof, and chuckled as he went to bed.

He imagined he was still angry and that his mirth was due wholly to that, but Mrs. Reilly, hearing the chuckles, reached her hand over and laid it on his hair.

"Ye do be all roight, Dan," she said sleepily. "Ye git unholy mad, aff an' on, but ut's the great heart ye've got, ould man."

For she knew that his angers were but escape valves for his temper.

And the next day Dan Reilly did not compel Umholt, at the point of a gun, to amputate his own eaves, for Dan Reilly remained in bed. It was the end of the week before the aches of the day on the roof permitted him to stand on his feet once more.

Neither did he carry his plan into action the next week, for early Monday morning the official surveyors appeared on the block, and Tuesday they announced that, instead of being entitled to two feet of the Umholt ground, Dan Reilly was trespassing six feet on the Umholt property. This would entitle Umholt to take all but about one foot of the porch on which Dan took his daily smoke. It was a hard blow, but Dan Reilly received it manfully.

"Misther Umholt," he said, "ut's a grand fool Oi've been makin' av mesilf wid yer roof, an' me bein' on yer propputy all the toime. Ut's loikely ye'll be cuttin' aft the porch av me, now, an' serve me roight."

Umholt looked dreamily at the bit of blue sky that he could see from his window, but it was Mrs. Umholt who spoke.

"Und vy shouldt ve vant to do such dings mit der porch for, hey? Dot porch don'dt bodder us, no? Mebby Bernard vould get sick ven he don'dt haf Mister Reilly to look at. It's shoost aboudt all der company Bernard gets, seeing Mister Reilly settin' on der leetle porch. No; ve leafe dot porch alone yet,"

"Now, do ye hear thot, Dan Reilly?" cried Mrs. Reilly. "Ut's ashamed av ye Oi am, wid yer day on the roof an' all. But," she added to Mrs. Umholt, "uf th' ould man do be havin' his hot fits now an' ag'in, ut's admirin' ye he is all th' toime, as Oi well know, an' we both loike yez fer good neighbors, Mis' Umholt, as ye are. An' Dan no less. For ut's in the naychur av him thot the betther his neighbors is th' madder at thim he gits. An' ut's proud we are to take th' porch from yez."

"Ach, dot iss noddings!" said Mrs. Umholt, lifting her hands in refutation of all merit.

Dan knocked the ashes from his pipe and nodded his head solemnly.

"Ut is thot, ma'am," he said politely, "an' ut's the rale loidy ye are, an' yer man loikewise. Oi'm not wan to make small av a big koindness, ma'am, but, uf Oi do say ut mesilf, as shouldn't, ut's gittin' even wid me ye'll be all th' same. For why?" he added, with a twinkle in his eye. "Day by day, as Oi set here, ma'am, an' look upon thot roof jist beyant me nose there, ut's mesilf will be sayin', 'Dan Reilly, remimber th' day on the roof, an' recollec', Dan Reilly, thot the biggest fool ye iver knew is the husband av the fri'nd av the woife av Bernar' Umholt -- long life t' him.'"