|

|

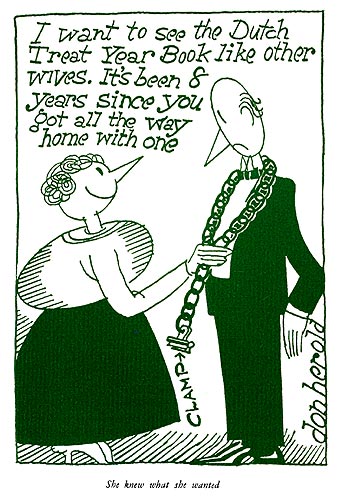

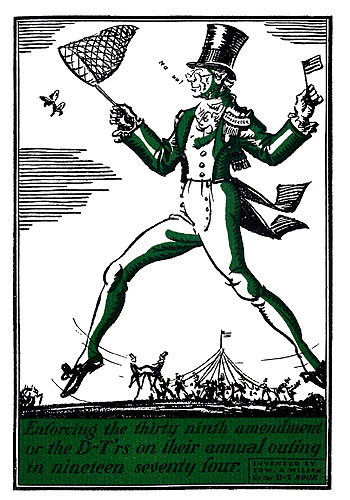

from Dutch Treat Club Year Book

Some Memoirs of a Very, Very, Very Old Dutch Treater

by Julian StreetBecause of my great age and my extraordinary memory -- a natural gift for which I claim no credit -- I am often asked to write my recollections, but hitherto I have refused, feeling that memoirs should above all be candid, and that certain great events with which I have been associated, involving as they often did the private lives of eminent personages, many of them my close friends, might well be allowed to remain, as Charles Hanson Towne, one of the wags of earlier days might have phrased it, "shrouded in mystery."

The recent deluge of biographies and autobiographies, some of them by men of my own generation, members of what might be termed the Dutch Treat Club's ancientregime, has, however, caused me to modify my decision, if only for the sake of correcting a number of inaccuracies, doubtless for the most part unintentional, which have been promulgated by men whose memories are less reliable than mine.

Let me, then, first take up my friend Ellis Parker Butler's generally sprightly volume, "Great Lovers of New York." Save for its inaccuracies this book would be Butler's masterpiece. His "Hudibras," though it made his reputation, was greatly overrated; his "The Way of All Flesh" was a distinct advance over the earlier work, and his "Pigs is Pigs" marked still another step forward.

In his "Great Lovers of New York" he tells us, correctly, that the Dutch Treat Club was founded by Thomas L. Masson and Robert Sterling Yard, but the question suggests itself: What sort of lovers of New York are these two men, when the former has his headquarters in Philadelphia and the latter his hindquarters in Washington, D. C.?

Butler moreover repeats the common error of identifying Yard as one who worked with William Caxton in the production of the latter's first book, whereas it was in fact not Caxton but Gutenberg with whom Yard was associated.

Butler himself, it should be remembered, spent the latter part of the Eighteenth and the early part of the Nineteenth Century not in New York but in Muscatine, Iowa, and it is all too plain that he has depended for much of his information on early New York upon idle gossip picked up, doubtless, at Childs' and the Automat, where truth is all too often sacrificed for a cleverly turned phrase.

He has, moreover, given too much credence to scandalous report. His version of the relations between Tom Masson and Nell Gwyn is not only sadly twisted but puts an entirely wrong interpretation upon what was merely a beautiful friendship. Butler has it that Masson lured the girl away from Monty Flagg who had usurped his (Masson's) dictatorship of the Dutch Treat Club, and he would lead the reader to suppose that Masson carried on with her scandalously, whereas in truth he merely read jokes to her in the gloaming. On this point I am backed up by such authorities as James Preston, Walter Trumbull and Reinald Werrenrath, prominent rakes of the period.

Similarly, Butler has chosen to make a great story of the famous altercation between William S. Walker and my kinsman, Rutger Bleecker Cortlandt Desbrosses Jewett, most distinguished member of the Street family, indicating that the trouble arose over the question which one knew Frankie Bailey best, whereas those who were present remember that the trouble started in a difference of opinion concerning the meaning of a line from one of Jack Sheridan's comedies, in which a young lady sitting on a radiator remarks: "My tale is told."

Butler, further, indicates some association between the tearing down of the old Hotel St. Denis and the fact that the first Dutch Treat Club luncheon was held there. There is absolutely nothing in this, the hotel having been torn down for other reasons.

James Montgomery Flagg, in his autobiography, "I," relates accurately enough the story of the founding of the Club at the St. Denis, but falls into a curious error when he declares that it was in the St. Denis that Jim Fisk was shot by Frank O'Malley. Flagg, whose memory a dozen years ago had already become so unreliable that he used to cut his best friends on the street, has confused the St. Denis with another hotel farther down Broadway, where the shooting actually occurred. There can be no mistake about this. Jack Cosgrave, Joe Chase, Martin Egan and I were there at the time; we all agree as to where it happened, but when we told Flagg of his error the old gentleman became very angry and roundly cursed us. His story is that he and Arthur William Brown were present when O'Malley fired the shot, having gone to the St. Denis to try to patch up a quarrel Flagg had with Jenny Lind shortly after the famous Scandinavian swimmer made her American debut at the Aquarium, then the city's centre of fashion.

Flagg was a great favorite with Mrs. Langtry when she lived in the brick house on West Twenty-third Street near Eighth Avenue -- or is it Ninth? Their friendship ended, however, when she playfully put a piece of ice down his neck; lese majeste was a thing he could not overlook; thenceforward he was cold to her, and I have heard it said that he never afterwards warmed up to anybody.

Ah, what stories that old house, behind its iron fence, could tell! It was a rendezvous for all the wits and gallants of our esoteric little group. There Bill Daly, fresh from Harvard, used to lecture on economics to the delight of Shelley Hamilton, who was at that time Secretary of the Treasury, while Jack Cosgrave pretended to believe in Rabindrinath Tagore and Paul Picasso.

Never shall I forget a certain night within those ancient brick walls. Rupert Hughes, Rea Irvin, Wallace Irwin, John Barnes Wells, Charlie Falls, and some others, I among them, had sat all night at the gaming tables playing vignt-et-un and drinking possets -- a beverage for which our charming hostess was justly famous. Towards dawn an argument developed between Shelley Hamilton and Aaron Burr, and this resulted in the famous duel back of the Ferry House in Weehawken. My recollection is that George Barry Mallon and Wallace Morgan were the seconds in this affair and that Bill Daly, who is still living, although on Riverside Drive, was the lookout. At all events, the score was 32-0. That was my memory of it, but I have taken the trouble to check up, consulting two men who, as young reporters, covered the story. Herbert Bayard Swope, then on the staff of the "Call," is one of them, while the other is Franklin P. Adams, at that time connected with the "Christian Herald."

The latter paper was controlled by the Pulitzers; the former by Frank A. Munsey, a brilliant young radical of whom much was expected. I have often wondered what became of Munsey; in spite of his great promise he dropped completely out of sight.

In those days the name of George Barr Baker was known to but a handful of men, and his brilliant son, George Barr McCutcheon, destined later to make a literary reputation under the nom de plume "Robert Barr," was as yet unborn. Baker was liked by everyone, but at that time no one suspected the extraordinary versatility which has since made him president of the First National Bank, Professor of Dramatic Art at Yale University and Dictator of the Republican Party.

It is not commonly known that the Adams brothers, Franklin P. and John Walcott, both gifted men, have another talented brother named Fred E. Dayton. The family name is Gibbs, but when they went into the chewing-gum business they dropped their patronymic out of pride, no Gibbs ever having been in trade.

Flagg in his "I," already referred to, makes some mention of my association with him in the laying out of Central Park, but garbles the story. He states, for example, that we originally intended the park to be a private garden surrounding a palace where he should live, to be known as the Flaggitorium. That however was not the original idea but was developed by him later. The park was laid out mainly by Flagg and myself, with some assistance from John Walcott Adams and Arthur William Brown, because, in anticipation of the wonderful growth of the city we perceived the need of a free love colony. That was our first concept of it, and the plan was that no one should be admitted except members of the Dutch Treat Club -- and of course their friends, especially on Lady's Day.

It will thus be seen that the idea in its inception was democratic, but as Flagg began to feel his power he changed the plan, and when he overthrew the Masson Dynasty he announced that the tract was to be his own private park and that the populace would be admitted only once a year, namely, between the hours of 1:30 and 3:30 P. M. on June 18th, his birthday, otherwise known as Flagg Day.

These are but a few of the memories, grave and gay, that surge flatulently through my mind as I gaze backward, down what Grantland Rice -- or was it Alexander Woollcott? -- graphically termed "the corridors of Time."

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 2:56:09am USA Central