|

|

from Photoplay Magazine

Movies Is Movies

by Ellis Parker ButlerA few days ago a producer bought the motion picture rights of one of my novels -- the one called "The Jack Knife Man" -- and paid $13,000 for it, all in real money. For this reason I become, in one jump, an important authority on motion pictures, and know all about them, and must be consulted by anyone who wants to know the truth about the motion picture situation.

As nearly as I have been able to figure it out, from a lifelong study of the motion picture situation --

to which I have given over a week of my time -- I can say that the outlook is bright. It is brighter than I have ever known it to be. The producers seem to be buying better material from better authors now than they did a day or two before they bought "The Jack Knife Man." This desire to procure the very best is a hopeful sign, and shows that some producers are eager to better the quality of the films offered to the public. I may say, here, that if any other producers want to go into the film bettering business I have still a couple of novels to dispose of on or about the same terms, and I believe they will do some of the best bettering on record.

While I am not yet the highest possible authority on motion pictures, not yet having applied for a divorce, I do feel competent to state in the strongest possible terms that I see a hopeful tendency in the willingness of the producers to use larger type in announcing the name of the author on the screen.

A prominent author said to me the other day: "The motion picture is not yet what it should be, but it is getting better all the time. I was paid twelve thousand dollars more for my last novel than I ever received before. This shows that producers are more artistic than they used to be. In addition to this, in filming my novel, greater care was taken in adhering to the eternal verities. In the Alaskan scenes from my novel I observed only three palm trees and two wads of cactus, and in the close up of my suffering heroine the glycerin tears were only as large as prunes, and not as big as cantaloupes, as they have sometimes been."

"Did the producer stick close to the text of your novel?" I asked.

"Very close," be replied. "And that is another sign of improved artistry. The changes made were very slight. Of course, my novel was the story of the love of an old man in the county poor house for an old lady in the Old Ladies' Home, in Cornstalk County, Kansas, and that had to be changed a little. They changed the old pauper hero into a young aviator just home from France, and changed the old lady heroine into the daughter of an Alaskan gold digger, but that was of slight consequence. I could not object to that. And Alaska does film better than Kansas, especially when it has to be filmed at Los Angeles. The country around Los Angeles is not a bit like Kansas.

"Is it like Alaska?" I asked.

"Except for the palms and cactus, it might be like it, if the resemblance was more apparent," he replied.

But how about changing your old lady heroine into a young girl? Wasn't that rather difficult?" I asked.

"Not at all. It was necessary. Any fool could see that an old lady could not be sixteen years old and have a baby face and long curls, so it was absolutely necessary to make the change. It was only necessary to change the wheel chair, in which the old lady sat in my novel, into a freight train. Then they put overalls on my heroine and had her father, the brakeman, go down with the Lusitania, which made it necessary for his daughter to take the job of brakeman on the through freight. So, of course, the old poor house lover had to be an aviator, and swoop down in an airplane and swoop the girl up from the top of the freight car when the villain. Roscoe, was about to brain her with a club --"

"I don't remember any villain named Roscoe in your novel," I said.

"Well, of course," said the author, "you wouldn't. He wasn't called Roscoe in the novel; he was a she; she was called Rosabelle. Rosabelle was the cat. Don't you remember how my old lady refused to marry my old man because he did not like cats, and she refused to give up the cat, and so they separated and lived alone the rest of their lives?"

"I see! So the scenario man turned the cat Rosabelle into a man villain named Roscoe?" I said.

"It was necessary," said the author.

"But, surely," I said, "they did not change that dear old cow -- wasn't her name Bossy? -- that the old man loved."

"No," said the author, "they did not change the cow. Not greatly. I insisted on the cow. So they only changed it into a bear -- a grizzly bear."

"My God!" I exclaimed.

"You needn't swear about it," he said, in a hurt tone. "There isn't such a great difference between a cow and a bear. They both have four legs."

Well, I was ashamed of him. I was disgusted to think any author would let a small sum of money bribe him to permit a sweet, idyllic romance to be murdered in that way.

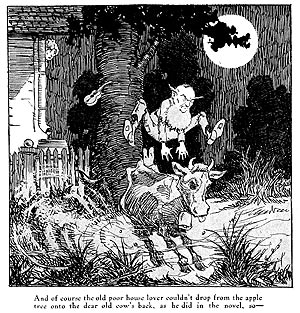

"At any rate," I said severely, "I hope you did not let them change that chapter I always loved so deeply -- the one where your old pauper hero climbs into the apple tree to serenade the old lady, and the cow Bossy stands under the tree, so that when the old man climbs down he alights astride of the gentle cow's back, and rides off slowly, back to the poor farm."

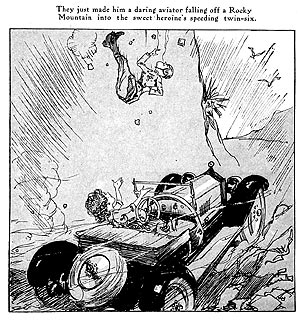

"Well, of course," he said, "we couldn't have the cow, because we had changed the cow into a bear, and we couldn't have an apple tree in Alaska, and we couldn't have a poor house because the old man was a young miner and lived in a cabin, so we just substituted one of the Rocky Mountains for the tree and substituted a twin six auto for the cow, and had the hero fall off the Rocky Mountain into the automobile and ride off triumphantly with the heroine. It made a swell ending. The hero was driving the car with his feet and embracing the girl with both arms, and the final caption was 'And he clung her to his heart until eternity grew old.'"

"My God!" I exclaimed again. "Did you write that caption?"

"No," he said. "The scenario doctor wrote it."

"Did you kill him, or anything?" I asked.

"Kill him? Why?" the author asked. "It's a good final caption, isn't it?" He was silent awhile, and then he said thoughtfully: "I can't understand it, either!"

"Understand what?" I asked.

"I can't understand why the film was a failure," he said. "Why it failed, after all the work we put on it -- I on the novel, and the scenario man rewriting it. It was a good novel; a big success as a novel. And the actors who took the hero and heroine parts were big people, too -- highly paid people. And they acted hard, too; they acted all the time. Close-ups, and tears, and stunts and everything. And yet people did not care for the film; even people who had liked the novel did not care for the film. You would think, if they liked my novel, they would like the film, wouldn't you?"

"But it wasn't your novel, was it?" "It had the same name. And it had my name as the author."

I saw that film, or another novel that had been twisted and warped and altered in just about that same way, and I did not like the film, either, although I had liked the story, and I think I know why so many picturized novels are disappointing.

Do you know how, when you go out to the country club to play golf and are feeling particularly strong and well, you often play your worst game because you "press"? "Pressing" in golf is putting too much into it -- trying too hard. It breaks the perfect swing of your club and you "top" the ball and your game is miserably poor. And, often, when you are feeling off your feed and weak and not much good you go out expecting to play the worst game you ever played and you surprise yourself and play the game of your young life.

In my opinion, that is one of the troubles with the filming of many good novels -- everyone who has anything to do with them "presses" all the while. The scenario man thinks he has to whangdoodle the story all over the place, and the continuity man thinks he has to rip the cover off the ring-tailed snorter, and the director thinks he, has to use all the pep in the old pepperbox, and the actors -- bless them! -- just naturally think they have to act.

One of the saddest things in the world today is to sit in an aisle seat and look at the screen and see the actors -- dear folk! -- trying to give every ounce of acting they have in them and ten ounces more. Because the actor -- honest soul -- is paid fifty thousand dollars a year, or twenty thousand, he or she feels duty bound to put sixty thousand or thirty thousand dollars worth of acting into each film. 'And that sort of whole-souled, going-every-minute acting spoils most novels that are screened.

Because motion pictures are not drama at all -- they are motion pictures. Even the speaking drama is not all rip-snort acting; not the drama that keeps on the boards week after week. Far more is this true of motion pictures.

If a scenario writer wants to compose a picture drama, meaning it to be "acted," with a star in the star part, and so on, it may possibly work out and onto the screen in a satisfactory manner, but a novel cannot be successfully done in that way.

Motion pictures are, first, last and all the time, pictures. They are photographs -- series of photographs -- which mean they are illustrations, just as the pictures in a story in the Saturday Evening Post are illustrations.

A good serial story in the Saturday Evening Post has, let us say, twenty illustrations. Each illustration tells a small part of the story, and we all like the stories we read to have illustrations, because they help us understand the characters, locations and events of the story.

It would be quite possible for the Saturday Evening Post to put more illustrations in each story. If one hundred illustrations were printed, instead of twenty, a great part of the text of the story could be cut out -- the pictures would tell the story. In fact, the Saturday Evening Post could, by using a thousand, or two thousand illustrations, with the proper captions, tell almost any story it ever printed, but those who know Mr. Lorimer's editorial ability know he would never permit the artist to change the story to suit the whims of the artist or of the artist's models. The artist would have to stick to the text, and the models would have to pose in a manner to picture the people the author wrote about and the things the author made his characters do. The result would be the story the author wrote, but done in pictures.

The objection to this method of putting a story before the public is that it would be tiresome to look at so many "still" pictures. What the film camera does is permit the public to "read" a story in exactly this way, but with life put into the pictures by making them "move."

When an author writes a novel he knows what and why he has written. When the public likes that novel it likes it for reasons that are in the novel itself. The novel is "good" because of the characters in it, the plot the author has created, the locale he has chosen, and the way the characters work out the plot in that locale.

Isn't it, then, almost willfully murdering all chances of success when the producer decides to make a "drama" of what is only a story, and when the scenario man whangdoodles the plot, and when the continuity man turns the whole thing back end forward and t'other end to, and when, finally, the actors spit on their hands and romp all over the place like old-style one-night stand "hams" and grimace before the close-up camera like sick apes?

The motion picture has come to stay because it offers a pleasant method of reading a story, and the motion picture will continue popular as long as there is celluloid with which to make films, but in my opinion the day when producers will try to turn every novel into a "drama," in poor imitation of the speaking stage melodrama method, is nearly past.

The producer who will succeed best, from now on, is the man who will set his ideal very high indeed, while the eternal melodramatic stuff will be relegated to the cheap picture houses, just as it is relegated, in printed fiction, to the dime novel.

Up to date I have sold just one novel for picture use, and I am waiting to see what the producer does with it. I don't want my cow turned into a Rocky Mountain grizzly bear. If I put an old lady in a wheel chair I don't want to see her screened as an eighteen-year-old vampire jumping from one airplane to another. I don't want my cats to become coyotes or my canaries to become hippopotamuses. It may be all right, and a tradition of the screen, but when I write about the Mississippi River I don't care to have the Ganges or the Nile or even the Amazon substituted for it.

"Movies is Movies" but an author, although only a poor mutt, does have some feelings. Up to date the producer has not telegraphed me asking permission to change the title of the proposed picture from "The Jack Knife Man" to "She Cut Her Husband's Gizzard Out," and I don't believe he will telegraph me, because there are two kinds of producers today. One kind does not want to make such changes, and the other kind just goes ahead and makes them without asking permission.

But I can tell you one thing: If "The Jack Knife Man" comes to your town and you see old Uncle Peter doing stunts in an airplane over Niagara Falls you can be mighty sure I didn't say he could.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 2:36:49am USA Central