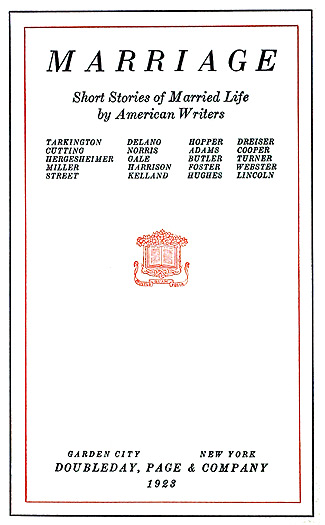

from Marriage

The Tenth Mrs. Tulkington

by Ellis Parker Butler

My only excuse for throwing George Tithers into the lily-pool at midnight is that I thought he was my wife Susan. As a president of a bank and a highly respected and weighty citizen I most seriously object to being called "Baldy," and I particularly object to being slapped gaily on the top of my head with an open hand. Or any other kind of hand. And I believed this Tithers person -- my wife's brother, I'm ashamed to say -- was in Europe. Naturally, then, when I had been dreaming that my wife was standing above me in a divorce court, denouncing me to the judge, and declaring that even the sight of my bald head had come to be nauseating to her, my first thought -- when I felt the slap on the head and heard "What ho, Baldy!" -- was that Susan was attacking me. In an instant I had leaped from the marble bench and had grappled with my attacker. George Tithers cried out a moment too late, for I had already given a mighty heave and had thrown him full length into the lily-pond. As my mistake became apparent to me as I saw George Tithers coming out of the lily-pond on his hands and knees, I apologized frankly.

"I beg your pardon," I said; "I thought you were my wife."

"Rather! I should think so!" George said as he emerged and shook himself like a dog. "But it's not a nice way to treat a lady, Tulky; is it, now? Wife-drowning isn't done in the best circles any more, you know. But, I say! Has it come to this, really? The little gray home in the West must be off its feed, what?"

Now, my home is not gray and it is not in the West; it is white marble and on Long Island; but I let that pass. George Tithers had -- in his silly way -- put his finger on the exact fact: our home was "off its feed," as he chose to say, and entirely off its feed. I made George remain where he was while I explained the matter fully and to its least detail. Toward the end of the first half hour, as the night grew chilly, his teeth began to chatter and a little later he sneezed many times with gradually increasing violence, but he listened patiently. This deepened my thought that George and his precious wife must be dead broke again, but I was glad to have even a dead-broke brother-in-law hear the truth about Susan and myself. That truth was that after twenty years of married life we hated each other. As a matter of fact, the reason I was on the marble bench by the lily-pool at midnight was that I had told Susan I would never again spend an hour under the same roof with her and that tomorrow we would begin seemly but immediate preparations for a separation and divorce. I had meant to spend the night on that marble bench.

"I say!" George exclaimed between sneezes, when I had concluded. "The little old trouble has become quite a snorter, what? Jolly full time the doctor was called, yes? Arrived in the nick of time, didn't I, Tulky? And, I say, do you mind if I ensconce myself in the pool a bit? The water seems a bit warmer than the air."

The idiot, I do believe, would have gone back into the pool, but that precious wife of his came out looking for him. She seemed to take his lily-pool bath as a matter of course, quite as if it was a habit of his to bathe in lily-pools at midnight, fully clad -- as I have no doubt it is.

"Bathing, George?" she said, after she had greeted me -- kissed me, mind you! "Be sure to have a brisk rub before you turn in. And you can come into the house now, Augustus; Susan has explained everything and the chauffeur is sleeping in the kitchen. Susan has taken his room in the garage; temporarily, I hope, but it is a very comfortable room. You do your servants well, Augustus. It is a lovely trait."

"Susan attends to the servants," I said reluctantly.

"Does she? She does everything so well, doesn't she?" said George Tithers's wife.

I might have said, in reply to that, "Too confounded well!" but I did not.

"The trouble," said George, when he had poured himself a chill-preventer, "is that Susan is a wife in a million. I'll say in eight million. You told her she was a wife in a million, didn't you, old top, when you were a newly-wed?"

"None of your business!" I growled.

"Ah! He confesses!" said George Tithers. "And now, Gussie, me lad, because she is just that -- a wife in a million wives exactly like her -- you are sore. What? Bored! Biting the old fingernails with ennui! Dead sick of dear old Sue, and dear old Sue dead sick of nice old Gustus! The trouble with you and Sue, me lad, is that you need a couple of stage-managers. That's Trouble Number One. And Trouble Number Two hangs on it -- you're both natural bigamists --"

"Stop right there!" I cried.

"Like all of us! Like all of us!" said George.

"Not another word!" I exclaimed, exceedingly angry.

"Whoa up!" George said then. "Stop here! The boss says stop. We're through, Amelia. I only meant to tell him of Lord Algy and Lady Mercedes, but he says 'stop!' and we stop!"

"Oh, Lord Algy and Lady Mercedes!" exclaimed George's wife. "The happiest two people! Such a happy pair!"

"Always marrying! Always marry and gay, what?"

The poor wretch laughed heartily at his miserable pun.

"So cheery and happy! Always divorcing each other and marrying somebody else, and marrying each other again so gaily!" exclaimed Amelia.

"Because a man gets tired of the dear old wife after twenty years, even if she is my sister," said George.

"And of the dear old reliable husband, even if he is the most respectable old baldy," said Amelia.

"Especially if he is the same dear old reliable husband," George corrected her. "It's the blessed routine that warps 'em, don't you think?"

"Rather!" said Amelia heartily.

"It's like being married to the bally old Westminster Abbey, what?" said George. "Act of Parliament needed to permit even the riotous innovation of a new tombstone. Not a new hair on Old Bald-Top in thirteen years! Not a new-style hiccough out of dear old Susie since the wedding bells!"

"Stop it!" I cried irritably, for he was patting the top of my head, the silly donkey. "Leave my head alone! What about this Lord Algy and this Lady Mercedes -- if you must talk."

"Oh, they're just off-again, on-again, gay little marriers, Augustus!" George said. "Tired of one wife, get another; tired of one husband, get another. It's done in their circle. A man does get tired of the same old wife. Routine stuff, if you get me. Deadly monotony, what? Sick of the sight of her; hate her -- what?"

"It's in us," said Amelia placidly. "The bigamy thing, I mean. Any man who can afford it and is not restrained by convention or his ethics hops about a bit; has a variety. King Solomon, the Sultan, Henry the Eighth, Lord Byron. And Tithy, here."

"In a way of speaking," said Tithers modestly.

"And myself, Tithy," said Amelia. "In a way of speaking, as you remark, darling. And Cleopatra, and the Queen of Sheba -- by all accounts."

"Now, stop this nonsense!" I said. "You know, both of you, that you do not run about after other men and women --"

"Well, rather not!" cried George. "He don't get us, Amelia; he's a bit dense. Tell him."

"Marriage," said Amelia, "is almost never a failure; married life is. Marriage is the first joining of two people together, and jolly sport it is with the getting acquainted intimately, rubbing sharp points together, and all. Somethin' interestin' all the while, what? And then, in a few years -- five, maybe, or ten, or twenty -- comes married life: the routine stuff. Awful bore, sometimes: same old wife; same old husband; same old ways, and everything! Nothing new! They get jolly well sick of each other, and no wonder."

"A man -- a man with a business to attend to -- can't be running around divorcing his wife every day or so," I said.

"Crickets, no!" exclaimed George Tithers. "He'd be doing nothing else; that's not the right card -- the right card is to marry the whole lot at the first jump off, if you get me."

"I don't," I said drily.

"You did it, though," said Amelia, with a laugh. "Susan did it, too. It's a poor stick of a woman that isn't a dozen women, and a poor stick of a man that isn't half-a-dozen men."

"What we mean," Tithers broke in, "is that you and Sue need to be stage-managed, what? You two have twenty roles in you, between the two of you, but you won't change. You, Augustus, keep the middle of the stage forever and a day as the Heavy Father, and Sue has been playing the Faithful Wife twenty long years. 'Twentieth Year of The Appearance of Honourable Augustus Tulkington and Mrs. Augustus Tulkington in Their Disgustingly Familiar Parts of Honourable Augustus Tulkington and Mrs. Augustus Tulkington,' what? It's not a wonder you want a divorce; it's a wonder you don't murder each other."

Amelia Tithers was looking at me thoughtfully.

"You can't grow new hair," she said, "but you might wear a wig occasionally."

"What ho, yes!" cried Tithers, jumping from his chair excitedly. "When he stages himself as the Conceited Elderly Ass, what? A toupee, what? And white spats! And a monocle? No, not a monocle. A monocle can't be done."

But it was done. It was not a complete success, it would not stick in my eye, but I dangled it from a string and learned to swing it around my forefinger quite well. Exceedingly well, I may say.

As anything seemed preferable to divorce, Susan and I, after thorough consideration of the matter in company with George Tithers and his wife, agreed to appoint George and Amelia stage-managers of our married life and I allowed them a liberal compensation. After a long consultation George and Amelia decided that it would be best for George to be my personal manager while Amelia managed Susan. I agreed to everything in advance, but I was surprised when George presented me with a sheet of paper at the top of which he had written "Cast of Characters." On this sheet were written six varieties of husbands, all men of my acquaintance, and no two alike. At the head of the list was written "January -- Self, prosperous banker." And following this was "February -- H. P. Diggleton, clubman, heavy sport," and "March -- Winston Bopple, flirt, lady-chaser," and so on down to "June -- Carey S. Flick, conceited elderly fusser, etc." July I was again to be "Self, prosperous banker." And so on for the second six months. As the month was now August I was to be, not myself, but a person resembling as nearly as possible H. P. Diggleton. For the month of August Susan was to have as her husband not myself but, to all intents and purposes, someone equivalent to H. P. Diggleton. George Tithers saw that I was fully equipped with the manners and habits of H. P. Diggleton; when he could not be sure what H. P. Diggleton would do he invented something new for me to do instead -- something Diggletonian.

I admit that as the day approached when I was to become a practically new and unknown husband to Susan I became keenly excited. This was not because I was to be another man but because I knew I was to have in Susan an entirely new wife. I had never been so interested in anything in my life. When the thirteen trunks, containing the thirteen complete sets of costumes Susan was to wear in her thirteen impersonations, came into the house and were carried to the storeroom I actually trembled with excitement as I saw them and noticed the huge white numerals painted on their sides. I say thirteen trunks because Amelia Tithers had decided that, month by month, Susan should be thirteen women. She felt that Susan, being a woman, was equal to the task, and by letting Susan be a different woman each month for thirteen months while I ran, so to speak, in a cycle of but six months, it would be many years before the same husband could have the same wife. If, for example, Susan should be Mary P. Miller in August to my H. P. Diggleton, there would be no danger that she would be Mary P. Miller to my H. P. Diggleton the next August, because if Mary P. Miller was wife No. 1, when August came again Susan would be wife No. 13. And the next August she would be wife No. 12. Thus a continuous novelty was assured.

On the glorious August morning when our experiment was to begin I opened my eyes and raised myself on my elbow to take a last look -- for twelve months -- at the old Susan Tulkington. She was not there! I leaped from bed, bathed, and hurried into the clothes George Tithers had supplied for my Diggleton impersonation, and hastened downstairs.

"Your wife?" Amelia Tithers said pleasantly. "Oh, you'll not see your wife this month at all! She is, this month, one of the gaddy ladies who fly from their husbands in the summer. Susan has gone to Newport, thence she goes to Alaska. You can expect her as the second Mrs. Tulkington on or about the first of September."

I can assert that Susan and I did not quarrel that August. In fact, I never loved and longed for Susan as truly as I did toward the end of that month. I wasted, so to speak, my H. P. Diggleton role on the desert air, but George Tithers kept me spurred to the role and I am sure I did well. I made use of all my clubs and I did enjoy them. I played more auction bridge than in all my previous life.

"Gus," one of my friends said, "I hardly know you! You're like a different man. Maybe you didn't know it, but you were getting stupid and stodgy -- you were getting in the 'old family man' rut. Well, bid 'em up; bid 'em up!" '

I met, toward the end of August, a banker from Nome. He had met Susan at Portland.

"Some wife!" he said enthusiastically. "Some lively lady, Mr. Tulkington! Just shows how folks can be mistaken -- Henry Torker who was down here last year said your lady was one of these house-broke ladies, one of the nice old family persons. Oh, boy!"

It was with some trepidation that I awaited Susan's return in September. I was grateful to Amelia Tithers for taking Susan far away while she was impersonating such a lively lady as Mr. Hutchins of Nome suggested she was impersonating, and I admit that I was glad I was to give her tit for tat, so to speak, since my September schedule called for me to be a Winston Bopple, lady-killer and flirt. After a few evenings of coaching by George Tithers I was sure I should be able to carry my Bopple role in a manner that would not cause Susan the least monotony. Two or three of the ladies in our summer colony seemed quite willing to assist me in giving the part verisimilitude.

When Susan arrived she gave me one kiss and hurried to her room, but Amelia Tithers paused a moment.

"You'll be surprised!" she whispered. "Susan is doing it so wonderfully! And our little practice trip came off splendidly. You'll never again think of Susan as a stodgy, stupid, married-old-thing sort of person. You just wait!"

When Susan came down to dinner I was indeed surprised. I turned from Amelia Tithers, with whom I had been doing my best to flirt, and gasped. Such -- well, such lack of clothes! Such abundance of long earrings!

"The vampire type!" breathed Amelia Tithers. "Doesn't she do it well?"

She did! For a few September days I did try to flirt with some of our female neighbours, but before a week was up I found I had enough to do in making love to Susan and in trying to crowd between her and the men who seemed to take her masquerading in earnest. We had one row, with Susan in slithy coils -- so to speak -- on the chaise longue, when I told her what I thought of her conduct and she called attention to mine, but we kissed and made up like young lovers. The next minute she was vamping old Horatio Peabody, the silly old fool! And I had to make eyes at his stuffy old wife in self-defense. It was, indeed, a hasty and hectic month, as George Tithers said.

"Thank heaven," I said to George, on the last day of September, "this month is over. I hope Susan is to be something respectable in October."

"I say, you know!" George exclaimed. "You don't know that wife of mine. Up and doing, what? Always a little bit more, what? Spread a bit more sail -- that's her motto, if you get me."

"You mean to tell me --" I gasped.

"Well, rather!" exclaimed George Tithers. "Upward and onward, so to speak."

He was right; Amelia must have told him. "Well-educated show-girl who is not just sure she has married the right man," was what Amelia had cast Susan for in October. It was with the greatest difficulty that I was able to maintain my role of a man who regretted his past and was seeking his solace in good books. It was indeed hard for me to sit with the second volume of Henry Esmond and see Susan making merry with half-a-dozen brainless noodles while her clothes were practically an incitement to unseemly familiarity.

"It has been a lovely month," Susan said at its close. "I did feel so free. I hope you're to be something retiring in November. I'm to be --"

"What?" I snarled. I do believe I snarled.

"Wait and see!" she said.

The next evening when I returned from my bank and met Susan I fell into a chair and stared at her. She, who had never used rouge, had used it too, too abandonedly. Her gown -- I can only describe it by saying that even Mrs. Hinterberry, who goes what is practically the limit, would have hesitated to wear it.

"Like the Countess of Duxminster!" Amelia Tithers breathed in my ear. "Chic, yes?"

I shuddered. I had read of the Countess of Duxminster; it was she who gave the notorious party at which she lost thirty thousand pounds sterling and then bet all her garments -- and lost! And this was but November, and Amelia Tithers's motto was "Spread a bit more sail," and there were nine more impersonations on Susan's list!

I closed my eyes and groped for the stair banisters. When I reached the upper floor I dodged for the stairs that led to the storeroom. There, in a row, were the twelve trunks. Number 4 was not there; it was evidently in Susan's boudoir. For a moment I stood before trunk No. 5. It was unlocked; so were they all. I put my hand on the lid and hesitated. After all, I could guess what might be in trunk No. 5. I might as well know the worst. I staggered to trunk No. 13.

Now, I trust I am not a coward, but I did not dare open the lid of that trunk. A dozen times I drew a deep breath and a dozen times I hesitated. I turned to trunk No. 12, to No. 11.

"Augustus," I said to myself, "be a man! Face this thing!"

I threw open the lid of the trunk containing what was to be, in effect, the tenth Mrs. Tulkington. At first the trunk seemed to hold nothing but a few red artificial flowers and some hay lumped in one small corner. I lifted these. There was nothing else in the trunk! The red flowers, as I looked at them, assumed a meaning -- they were a wreath for the head; the hay was sewed to a narrow band. There was very little hay and it was extremely short hay. Visions of Hawaii and the South Sea Islands flashed on my brain. I saw my Susan on a sandy beach. In my imagination I could see nearly all of the beach -- and nearly all of Susan! I felt sick; suddenly and extremely sick! So this was to be my wife! This was to be the tenth Mrs. Tulkington! I could feel the cold perspiration oozing out of my pores. My Susan in a hay lamp shade and a wreath of red petunias!

I hardly dared turn my eyes toward trunk No. 11. I dared not raise the lid; I could think of nothing but Eve -- Eve in the Garden of Eden. I lifted the trunk by the handle and shook it. Nothing! There was absolutely nothing in that trunk! And beyond it stood trunk No. 12. And beyond that stood trunk No. 13.

I went down the stairs slowly. Five times I stopped and stood, trying to overcome the trembling of my limbs; trying to regain my usual composure.

This unseemly business had gone far enough; trunk No. 10 might do for a Lady Mercedes, but for a respectable American wife -- no! The tenth Mrs. Tulkington might please Lord Algy, but as for pleasing Augustus Tulkington -- no! I met Susan in the hall. I grasped her arm firmly.

"Susan," I said, "I have had enough of this! I have had plenty of Susans."

"Augustus!" she cried, and threw her arms around me. "Augustus, I have had more Augustuses than I could bear. I want just my own old Augustus! I want my plain old Augustus!"

"And I," I said briskly, "want nothing but my same old Susan. This whole business has been nothing but idiocy. We can vary the monotony of our married existence without committing imitation bigamy by retail and wholesale."

I was tremendously relieved, for I admit now that I had been tremendously frightened. The tenth Mrs. Tulkington had upset me.

"Susan," I whispered firmly, for I was not going to let her come under the influence of Amelia Tithers another moment, "go up to your room and prepare for a journey -- a journey with your own husband. You are going to Palm Beach with your Augustus, a respectable banker and married man. In five minutes the car will be at the door. Hurry -- for we have no time to waste. But, Susan!" I added as she turned to hurry up the stairs, "Susan! Will you tell me one thing? What was in the eleventh trunk?"

"Nothing, Augustus," she said, her hand on the rail.

"And in the twelfth trunk?" I asked with a deep breath.

"Less than nothing, Augustus," said Susan.

I shuddered to think of what a wife may be capable when driven to it by deadly routine.

"And in the thirteenth trunk, Susan?" I asked hoarsely.

"Why, you old silly, my own clothes," said Susan with a laugh; "the clothes I was wearing when Amelia and George came."

"Oh!" I said stupidly. "Oh! Well, you've no time to pack anything; you'll take the thirteenth trunk."

From Palm Beach I sent a large check to George Tithers, and he and Amelia were gone when we returned. That was several years ago, but I cannot persuade Susan to allow me to have those twelve trunks thrown out of the storeroom in the attic.

"No, Augustus dear," she always says, "I know now that monotony is the one great curse of married life, and I love you so dearly, Augustus, that I want always to have a few of dear Amelia's trunks to windward."