from Harper's Bazar

The Fifth Commandment

by Ellis Parker Butler

An aged woman of the world, who has been in her day the acknowledged leader of society, admits that she has certain rules of conduct which have been the secret of her noteworthy success. Why was she unlike other social leaders? Why was her word law in her community? Many admirers and more rivals have wondered. "There is something in you greater than yourself," some one once said to her. In a question of moral responsibility -- whether her niece shall sue for a divorce or not -- she invokes her rules and they answer the question for her -- in a way which will perhaps prove a surprise to most readers of this clever and intensely interesting story of present-day life in New York.

John, impersonal as a uniformed mechanism, drew aside the portiere of the stately room, admitting Anne, and having closed it behind him he again effaced himself. For a moment Anne, fighting for self-control, fumbled at the fastening of the soft fur that enwrapped her neck. Her interview with her mother had been most painful and had left her emotionally tremulous, and the short drive to her aunt's door had hardly sufficed to get herself in hand. Her eyes were still red, but when she pushed back her veil and glided across the room to where the old lady sat in the high-backed chair, she felt she was at least sufficiently in control of herself to be able to avoid making a "scene," as Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne would have characterized the hysterical weeping to which Anne had given way at her mother's.

"Aunt Ellen!" she murmured, in a tone that was an appeal, as she dropped on her knees before the old lady and bent her head, partly to kiss the delicate hand of her aunt, and partly to conceal the emotion she did not wish too fully to betray.

"There, there, Anne!" said her aunt. "It may be as bad as you think, but that is no reason why you should threaten my poor old knees with all your hat-pins. If I have to listen to a five act tragedy you might as well take off your hat. Your eyes are red. Where have you been weeping?"

"At mother's," answered Anne, raising her hands to unpin the hat.

"The only safe place in New York for a married woman to weep," said Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne. "Wherever a woman weeps, except at your mother's, she sets tongues wagging, but your mother --! I tell Jane she should put out a sign -- 'Tears at all hours,' and have her cards engraved 'Weeping done on short notice.' You're safe if you wept there. Everyone weeps there."

Through Weeks of Doubt

"Mother is sympathetic," said Anne, rising to put her hat on a chair. She felt quite safe now. Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne's very manner was a discourager of strong emotions. Strong emotions were abashed before her perfect poise; perhaps they felt tawdry in her presence.

"She is the soul of sympathy," said Anne's aunt, "and after you have wept with her you come to me. Humph! Jane comes to me herself. When she is thoroughly wept out she comes to me for worldly wisdom, I suppose. Well?"

She spoke the word, not brusquely but gently; for the tragedy in Anne's face was real. The anguish of hours of struggle with her problem, and the awfulness of the problem itself, were set deep on her face. The remaining evidences of her tears were a lesser matter, like some fugitive stain on the surface of a mask, while the real attestation of her trouble was deeper, like an under-glaze, or like the pate of her soul itself. If Anne hesitated before plunging into the five act tragedy, as her aunt had not inaptly termed it -- it was from pure reluctance to begin again so soon the tale she had poured into her mother's ears. Only the hope that she might, and the belief that she must, find her solution in her aunt's final dictum could have induced her to begin again the long recital.

The two hours she passed at her mother's house had been the most terrible hours Anne had ever spent. Even the long nights when she lay tossing on her bed trying to unravel the puzzle alone, and meeting at every crossing of the threads a new entanglement that threw her mind back upon itself in a sort of desperate blankness, had been less awful. She doubted if she had suffered as truly during any of the days, the events of which had led her to seek her mother's advice.

An Unprecedented Case

Anne had fled to her mother in a sort of loving desperation, feeling sure that a broad maternal sympathy could and would cut the Gordian knot of her doubts. She had not gone in search of a strengthening of the logic she had herself tried to muster on her side of the complicated situation. She had thought and thought until she was ready to throw herself on the floor and scream aloud, just to be rid of her thoughts. She had become hopeless of a rational solution and wished only to be urged to action, however irrational, and by action she meant, and seemed only able to mean, leaving Edward immediately, with the divorce as the early ultimate.

Of divorce Anne had, herself, no fear. In her stratum of society divorce had long since become the recognized and logical means of solving troubles even less annoying than this in which she found herself involved, but there was an uprightness of judgment in Anne's nature that, when her own affairs were concerned, made her a very "Daniel come to judgment." What made it worse was that, in all her experience, there had been no case quite apt as a precedent. It was one of those cases of incompatibility, with a thousand excuses for and against every seemingly studied affront of either party, and all the aggravating cross-purposes and side-lights that modern life has created and made possible. Sometimes, when she herself felt most guilty and her whole course seemed as impossibly selfish as if it had been that of another woman, and when her contrition was greatest, the memory of some word or act of Edward's would flash into her mind with stinging force, driving her to righteous rage. Or again, when her anger against him was white-hot, some word or act of her own would force itself into her mind, and seem, for the moment, to excuse everything Edward had ever said or done.

The Appeal to Mother-Love

Out of all this -- and, naturally enough, Anne thought in terms of the actual words and acts and by-plays that had been passed and had occurred -- Anne could make nothing satisfactory as a solution. Study her case as she might, she could not rid herself of the fear that, after all, society and not Edward might be at fault, and that she might be doing him an injustice if she appealed to the law. It was when she had reached the point of feeling that the untangling of this knotted skein of right and wrong was beyond the skill of her mind, that she carried the miserable affair to her mother. In her heart, if she could have admitted it, she knew she sought only the angry mother-protection -- the advice to come home to the mother-arms. She wanted only the blind mother-grasp of any one salient wrong; the irrational deciding word that she herself dared not choose through reason.

She wanted to lay the whole case before her mother, as before a just judge, giving Edward the benefit of every doubt, knowing that her mother would give her the benefit of every doubt. She had no question of the final decision.

The result had been the direct opposite of what she had expected. For two hours Anne had talked, tracing each thread of the matter through all its intertwinings and omitting nothing, while her mother listened with drawn face and nervous hands, and when the judgment had come it had come with sudden tears and with no regard to the premises.

"The Dishonour of It!"

"Anne! Anne!" her mother had moaned; "surely you do not think of that! A divorce -- and none of us has ever been divorced! Oh, you can't be thinking of that -- the disgrace of it, the dishonour of it! You cannot mean that!"

"But, mother! It is not a disgrace now. For just cause, if my cause is just, I need feel no dishonour. It is not so rare an event that the world stands open-mouthed. It is not a question of that. It is a question of whether I am justified -- whether I am at fault."

"The dishonour of it! The dishonour of it!" her mother mourned. She seemed incapable of anything but the merest repetition, copiously watered with tears. "No Willington, no Wolcott, has ever had to suffer that disgrace. Surely, surely, you cannot be thinking of that, Anne!"

"It is no dishonour!" Anne exclaimed at last. "I should feel none. It is for me to feel it, if anyone, is it not?"

They had both wept, as mother and daughter will, and Anne's mother tried to dry her own eyes now. She really tried to be brave about it, to see Anne's visioning, but she did not quite succeed. Indeed, she did not succeed at all, either in drying her eyes or in finding Anne's point of view. She was too old, and had cherished the old family pride of freedom from the divorce court too long, to be able to convince herself or be convinced. When at last she had succumbed to Anne's tears she left Anne with none of the feeling of a strong impulse the younger woman had hoped to find.

The Appeal to Caesar

"I am sure Aunt Ellen would think I was doing right," Anne had said, when the tearful surrender had been made.

"Aunt Ellen knows the world better than I," Anne's mother had admitted. "Go to her. Tell her, Anne. Tell her everything. If she is of your mind, I will resign myself to the disgrace. Ellen will know what is best."

Aunt Ellen was "aunt" to no one but Anne and her other nieces and her one nephew. To the rest of the world, which included thousands of industrious newspaper readers, she was Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne -- the Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne whose mere passing in her sumptuous car was an event comparable with the spectacle of the fall of the Campanile or Dewey on Dewey Day. The newspapers, or more exactly, the society reporters of the newspapers, loving superlatives, still wrote of her as "the society leader," but this was no longer true. Its convenience was greater than its truth, for it was easier to continue to speak of one "leader of society" than to attempt to feature the many lesser aspirants for the position Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne had voluntarily relinquished. In the social semi-anarchy that had followed the laying-down of her sceptre there had been a scramble, but none of the younger matrons had been able to take it up. "Society" indeed seemed to have been held together by Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne's mastery alone, and threatened now to disintegrate into "sets." Many, wearied by the vagaries of the younger sets, hoped Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne would resume her sway, But of this she had no intention.

Her Secret of Power

The truth seemed to be that, after the grand ball that was understood to be the old lady's ceremony of abdication, society entered upon a new era, and not a better one. Some restraining motive seemed lost. It was not that society was more immoral, but less moral. Even that seemed to he putting it too strongly. Just as there was in Washington -- I have Emerson's words for this -- something greater than the man's deeds, there had been in Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne's leadership something greater than the manifest qualities she displayed. Of scores of brilliant women -- some far more brilliant than Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne had ever been -- who aspired to her vacated throne, there were many who combined all the visible and tangible qualities of the lost leader, and yet none was accepted, or seemed likely to be accepted, as Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne had been, unquestioningly. The fact was that none seemed to possess, us an underlying strength, a certain quality that had been recognized in Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne by even the least observing. Just what this quality was remained a mystery. It was felt but was difficult to define. In the last analysis it seemed to be a marvelous power of judgment combined with an incorruptible sense of justice.

As she sat in her high-backed, winged chair, with Anne seeking words to begin again the long recital of her complex troubles, the old lady had none of the Darby-and-Joan quality of Anne's mother. She was a rather severe, worldly old woman, like a Queen Elizabeth aged and Americanized. No one would question that she was of the world, worldly -- proud of her sceptre-swaying past, proud of her present, and proud of all the Wolcotts and Van Dynes that ever had lived or ever should live. She was even proud of the fact that Anne should come weeping to her feet as to the only person capable of advising her in her overwhelming crisis.

"Well, who is the man?" asked the old lady suddenly.

The question was not cynical. It was a shortcut; a direct road to the heart of the matter, learned by years of contact with life, and one she had used many times before. It pleased her to see Anne lift her head quickly, as if in response to a rapier thrust into the heart of things, as a conjurer is pleased, after many years, to see his sleight-of-hand still cause mystification. But the glance of horror Anne offered in exchange was too real for trifling.

"It is always a man, at your age," said her aunt. "Who is it?"

"Edward," said Anne, reassured by the absence of any cynical smile; "I think I shall leave him."

"But These Husband Affairs!"

"As bad as that?" said her aunt. "I hoped it was only some other man. Other men affairs are so much easier to arrange. I always know how to advise where there are other men; I suppose we old scandal-mongers become expert. But these husband affairs! Well?"

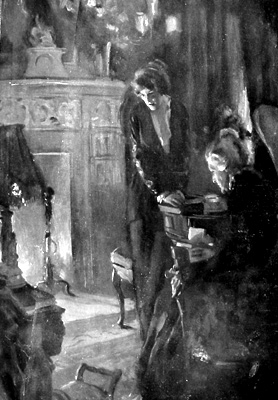

The girl began calmly enough. As she had told her mother, so she told her aunt, going into the matter dispassionately, laying evidence against evidence; but despite herself, before she had spoken long she began walking the room. From time to time her aunt shook her head sorrowfully. Once she cried out -- "Stop, Anne! Wait!" and the girl paused, one hand on the back of a chair, until her aunt bade her continue. When she had finished and had sunk into a chair, exhausted, she burst into tears, and her aunt, despite the art of the peerless Marie, looked quite as old as her years justified. For many minutes the older woman sat staring -- not at the fire -- but at the medallion of Cupid and Psyche cut in the pediment of the great marble mantel. She was silent so long that Anne raised her head, fearing, with a quick rush of anger, her aunt had fallen asleep. But she had not.

Over and over, in her mind, the old lady was turning the tale Anne had told, seeking the salient point and not finding it. Bit by bit, and part by part, and as a whole, she was testing it by some inward standard of her own, only to find the tests fail, as if Anne had brought a colour to be tested by the hues of the spectrum, and the similar colour eluded and could not be found.

The Social Dictator

To Anne the time seemed interminable. Less trying would be the hours while she waited for the verdict, if, at last, her aunt should judge a divorce advisable, and the affair went to the courts. Of that verdict, with the laws as they were, she had little question. Of her aunt's she could foreguess nothing whatever from the motionless features.

"I can get a divorce," Anne said at length, unable to bear the silence. "There are several states where that can be done."

"Yes," said Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne; but her voice sounded far-away. "Yes. You can get a divorce. No doubt of it. No doubt of it."

"Well, shall I?" asked Anne.

"That is it!" said her aunt. "That is what I am trying to decide. Whether you should or should not."

"Should not?" exclaimed Anne. "Is there any reason why I should not. Is there any reason?

"There are no children, if that is what you mean," said her aunt.

"Oh, children!" exclaimed Anne more impatiently. "And if there were? That can all be arranged nowadays. I mean, isn't it the best thing I can do? Isn't it the only thing? It is my own life I have to live."

"Let me think a little longer, Anne," said Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne. "You cannot know how many times I have been called upon to settle such affairs, as this, and I have seldom made a mistake. Let an old woman have her own time. I'll find the key, I have no doubt. I have found them in cases as involved as this. You do not know what a tyrant I was, and not so long ago! If you knew how many wives have come to me, because they knew I could close every door against them if I wished -- if they went contrary to my desires. Oh, I have been a dictator in my day, Anne! And I was never squeamish. Many a time have I said 'Go, get your divorce and -- come to my ball on the seventh.' And quite as often I have said: 'Go get your divorce if you wish but -- if you do, send back the card for my reception on the twelfth.' I've been a just judge, Anne, but I have my laws, and they are as strict as the laws of the Medes and Persians, whatever they were."

Not One Life Alone

She dropped her hand to her knee and lowered her eyes to the glowing coals in the grate.

"No," she said slowly, "it is not your own life you have to live. It is never your own life alone, living as you and I must live, Anne. A savage -- some savage in the wilds, far from civilization -- might think he was living his own life, but you and I cannot think that of ourselves. Our own lives are the smallest parts of the lives we live. I have seen that so clearly that sometimes I have been reproached for my officiousness. Some even said I misused my power; that I ruled arbitrarily on things that did not concern me, casting out of what the newspapers liked to call the 'sacred circle' some least of the friends of my friends. But I was right! We do not live our own lives. Even those with whom we least often come in contact live our lives for us, as much as we live them for ourselves. And we live a part of their lives.

"It is not your own life you have to live, Anne. When you are wrong we are all wrong, as one bad drop of blood affects the whole body. We can try to ignore you; we can turn our backs on you; we can drive you to the farthest island of the sea, but even so you cannot live your own life only. That is what society is -- it is a goblet of water into which you fall, a single drop, and, once a part of the whole, you can never separate yourself or be separated. I may take a drop out of the goblet, and call it you, and cast it away, but it is never the same drop that was put in the glass. Part of yourself you must leave, and part of the rest of us you must take with you.

"But What Shall I Do?"

"Do you imagine that I have lived my own life? Hundreds have lived my life for me, and are living it for me now; and I am living a part -- and it may be a great part -- of the lives of all those I know. Do you know Miss Hulda? Whose life does she live?"

Despite her trouble Anne smiled faintly. Who did live Miss Hulda's life, indeed? The gentle old maid, welcome inmate of Anne's mother's home, surely did not live her own life. Each act of every day was shaped to fit into the lives about her without friction, until Miss Hulda's life was but the outline of parts of the lives of others.

"But this is different --" Anne began.

"It is more complex, that is all," said her aunt, "just as your trouble is more complex. And yet the solution of your trouble is not so very difficult. You have studied the complicated warp and woof; the tangled threads of your rights and your wrongs -- yes," she added quickly, as Anne was about to speak, "and Edward's rights and wrongs, as a dramatist studies a new plot to find a solution of a new complication of the old triangle puzzle, and what do you reach at last? New indecisions! We never reach the goal of satisfaction by following any path in such a maze."

"But what shall I do? What shall I do?" cried Anne. "To whom can I go?"

"What did your mother say?" asked Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne.

"Aunt Ellen! Would I have come to you if mother could have helped me? She did not understand at all. She did not try to understand. It meant nothing to her. She did not try to find the right or the wrong."

"I Saw Why They Failed"

"That is like Jane," she said. "Thought only of her old-fashioned ideals, I dare say. Hadn't a word to say except that it would be a disgrace to her, had she? Oh, I love that in Jane! Such godlike selfishness. There was never any doubt what Jane would think from the day she was ten."

"Please!" begged Anne. "Mother means the best."

"Of course she does," admitted her aunt. "I should know my own sister, I hope. So you had to come to me, poor child. Well, I am a wise old woman -- wonderfully old and wonderfully wise." She laughed. "Like some old woman in some fairy tale. Yes, I am wise," she said in good earnest. "If I had not been could I have ruled all those women -- all fighting for my place -- those many years? Would they still come to me? No indeed!"

She shook her head and smiled.

"Anne," she said, "hand me the little book you will find in the drawer of my escritoire there. That is it. Years and years ago, child, when people began to talk to me and say I was a leader, I wrote something in this book. I knew the tragedies of so many other women -- women who had glowed as the brightest lights of the circles I was to rule, only to be thrown down and put aside -- and I could not bear the thought that I too might burn brightly for a time and then be extinguished in the same way, and for the same reason. Oh, I was an ambitious young thing! I thought and thought, and lay awake at night to think, and I studied all those who had failed, and I saw why they had failed. So I wrote in my little book."

She opened the book at the first page.

"Once," she said, "a newspaper woman, a very bright woman, came to me and asked me to write down the seven secrets of my success. She wanted to print them."

"What nonsense!" said Anne.

"That was what everyone said when they read them," said Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne. "Of course I did not tell her, but she imagined seven secrets for herself, and printed them, 'The Seven Secrets of Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne's Success'! I remember one was 'Patronize only the best gown-makers.' As if that could be a secret of success. Every woman does that, if she can afford it. No, she was quite wrong. Even in the number she was wrong. My rules were ten."

What Makes Women Great?

"Not truly!" exclaimed Anne.

"Yes. I wrote them long, long ago, and they are the secrets of my success. Other women felt that I had some advantage, but they never guessed. I was -- different. They tried to be as I was. They copied my balls, my dinners, my teas -- even my hair! And my gowns, and the perfume I used, and my way of speaking. Even my smile -- imagine smiling another person's smile, Anne. They tried to be wise; to give wise advice because I gave wise advice, but -- You know Bishop Leamington?"

"Yes," said Anne. "What of him?"

"Nothing, except that something he said pleased me. It was after one of my balls -- the Orchid Ball, before the orchids were known at all -- and everyone had complimented me and flattered me, of course, saying the ball had been another of my triumphs. Mrs. -- well, her name does not matter -- had just said 'After this anyone should know why you lead us all, dear Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne!' and the Bishop, when she had turned away, shook his head and smiled. 'They cannot see,' he said. 'They are all blind. Only a few of us know that orchids do not make men or women great. But there are a few of us,' he said, 'who know the secret. There is something in you greater than yourself.' And he was right, Anne."

A Solution of the Mystery

"I have felt it, too," said Anne. "It is something mysterious."

The old lady in the winged chair almost chuckled, so happy was the intake of breath.

"They all say 'mysterious,'" she said, much pleased. "Because they cannot understand. Because 'society' has never known anything like it -- like my little book of rules. When everyone was puzzled, I could speak with words like a blow straight from the shoulder. And I can still speak, Anne."

The girl pressed her hands to her heart. She waited her aunt's next words breathlessly.

"'Myself when young did eagerly frequent

Doctor and Saint, and heard great Argument

about it and about: but evermore

Came out by the same Door where in I went,'"

quoted her aunt laying her hand on the open page of her little book. "And so have I heard great argument many times, as you have argued, but always, when all was said and all was explained, and I appeared to be thinking of the pros and cons, I was but testing the case by my little rules, my infallible rules. You must go back to your husband, Anne."

The younger woman opened her mouth to protest, but her aunt -- now in every line of her face the great Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne -- raised her hand, and she was silent.

The Rule That Applied

"You will go back to him," said Mrs. Wolcott-Van Dyne gently, "and you will not find it so hard, for you know I know what is best. Each day you will see more clearly that I am a wise old woman and know the world. Never, since I first wrote them in my book, have I had to change one of these rules, and never have I had to regret what I have ordered because of them."

Anne bent to pick up her furs, and the movement was like an obeisance of surrender. The older woman looked at her with a glance of pride and affection. The girl was a thoroughbred; she could take punishment without wincing. Now that the judgment was rendered she would bear her head high, and if she suffered, she would suffer alone.

"It was hard, Anne; hard for me," said her aunt.

"I know," said the girl gently.

"I had to think of your mother," said her aunt.

"Of mother?"

"To nothing that you told me," said her aunt, "did any of my rules apply. You thought I heeded great argument about your trouble and about? No! None of my rules applied. But some one always does apply. Do you wish to see it -- the one that did?"

The girl bent over the page, where the slender finger pointed out one of the Ten; and as she read, the trouble left her face, and she understood:

"Honour thy Father and thy Mother, that thy days may be long in the land that the Lord thy God giveth thee."