|

|

from Liberty

Chips

by Ellis Parker Butler

The quaint taxicab, which I was the only one Chips had been able to get because of the general exodus from Wedmore College, drew up before Harley House, and Chips and Cassie Carr heard the honk of the horn and came down carrying their suitcases. They were the last of the girls, all the others having already gone to the station.

"Heavens!" exclaimed Cassie as she saw the topless and rusty old Ford. "Look what the cat dragged in!"

Eddie Smar, the chauffeur, leaped out of the car and came running up the walk to take their suitcases. He pulled off his cap in an excess of politeness that showed how grease-stained his hands were.

"Say, I'm sorry I had to get you with this old wreck, Miss," he said. "I wouldn't have if we'd had anything else left in the garage. Everybody wanting to go away on this one train -- making four-five trips with some of the cars. I don't generally go out with a car myself. Honest, I'm sorry! Well -- I won't make no charge for taking you down. The next time --"

"What are you talking about?" asked Chips, her whole body stiffening and her head going up. "You know I didn't telephone until the last minute. You know it's pure accommodation for you to leave your garage and come for us at all. Certainly you don't have to act like a worm, do you?"

She stressed the personal pronoun as if there was someone who did have to act like a worm, and Cassie exclaimed "Chips!" in something like horror. Eddie Smar grinned.

"Well, you young ladies up here at the college make such a kick if everything ain't just so," he said. "All I meant --"

"We have just about three minutes to make that train," Chips said coldly, and she opened the rusty door herself and got into the car. Eddie put the suitcases in front and Cassie got in beside Chips. She put her chubby little hand on Chips' long thin one and gave it a slight pressure.

"What's that for?" asked Chips.

Cassie drew her hand away and looked shocked. It had been a hand pressure of sympathy and understanding, saying that she knew well -- and forgave, perhaps -- the feelings that had led Chips to resent Eddie Smar's profuse apology for the car he had had to bring.

Eddie did not know, of course, that they were now full-fledged graduates of Wedmore with their diplomas safe in their trunks. Eddie thought, doubtless, that they were juniors and would be back in the fall, and he had been servile about the car, Cassie guessed, because he was looking forward to their taxi trade later on.

At the station, which they reached just after the train pulled in, Chips thrust a dollar into Eddie Smar's hand. She grasped her suitcase and crossed the platform with Cassie following her. Many of the girls had already crowded aboard, and Chips, hurrying, crowded close behind a traveling salesman fellow who struggled with two huge sample cases at the car step. Her knee hit one of the cases and the man turned his head.

"I'm sorry. Beg your pardon!" he said, and Chips gave him an irritated glance.

"What for?" she demanded. "I bumped into you. Will you please get on the car and stop talking?"

"Why, Chips!" Cassie gasped. "Why, Chips!"

"Oh, be still!" Chips exclaimed. "We'll never get a seat -- see them crowding in at the other end."

But seats they did get. At the junction they changed to the through train and there seats awaited them in the chair car, reserved well in advance. Here the perspiring porter carried their suitcases aboard, showing them their chairs, and hurrying out again to aid his other passengers aboard. The car moved with heavy ease along the better track. Chips cast her hat on to the rack above her head and lay back luxuriously, and Cassie stood up to wave her hand and smile at the other Wedmore girls who were in the car. Now they were indeed en route for home, and Wedmore was of the past. Chips closed her eyes.

She opened them again almost immediately and the glance she threw at the back of the seat ahead of her was almost a scowl. Of the woman in the chair she could see nothing but the top of the hat and some sort of pompom affair that stuck straight up, but the pompom and the voice were enough to tell what the woman was -- one of the "always complainers," one of the "never satisfieds." She was scolding the apologetic colored porter, her voice a whine and a rasp.

"Yes'm. Ah's sorry, but this is the seat you engaged; this is the seat your ticket calls for," the porter was saying in the most extremely fawning voice. "Ah'd let you have another seat in a minute, lady, only this car is jam full."

"And do I have to sit facing this partition all the way --"

"Ah can turn your chair facing the other way --"

"And ride backwards? I can't ride backwards! I should think this railroad --"

"Yes'm. Ah's sorry," the porter repeated humbly. "I sure would fix you up better was there any way I could, lady. If you just excuse me now, I got to --"

Chips snapped her hand into a fist and hit the upholstered arm of her chair angrily. Blatting excuses! Lying down to be walked upon! Being worms! Asking pardon for living! Oh! From anger, from irritation, or from some other reason tears came into her eyes. She shook them away with a jerk of her head.

"If you don't like my back, you can look out of the window," she said over her shoulder, and Cassie laughed.

"Chips, you're terrible!" Cassie said and added, "Do what you please with your back; I'm going to take a nap." And she did.

Chips stared out of the window. She was dark, almost Spanish in her pigmentation, and her eyes seemed black ordinarily, with a reddish flame when she was agitated. There were two little up-and-down creases that showed between her eyebrows when they came down in a frown, and her face was apt to show a trace of sullenness when things were not going to suit her, a sultriness that burst into flashes of something very much like anger. This had come from her father, evidently, although he was no longer living to permit a comparison. Her mother was blonde enough, and gentle; "meek and long-suffering" was how Chips thought of her.

In spite of all this, Chips had been a favorite all through college. Even her quickness to resent and to say her mind -- which had made them say she always had a chip on her shoulder, thus leading to the name they had given her -- had made her stand out as a character where so many were monotonously nothing much but nice girls. She spoke her mind when she felt it was time for someone to speak up, and usually she spoke it with rather more energy than was necessary. What saved her was that her outbursts left her unaffectedly sweet tempered and not sulky. Her resentments accumulated and exploded and were followed by normal weather.

Just now she was a Leyden jar charged to the exploding point. For one thing her mother had not been able to come to the graduation; she had written that she was feeling so poorly she did not dare make the trip, and that the inn was demanding every moment of her time, June being the beginning of the motoring season. Chips, frowning, did not believe any of this; she laid her mother's absence to crass kindly poverty, actual lack of money to make the journey, the strain of keeping Chips in college four years from the income of the inn having been all Mrs. Moreton could manage. The graduation had meant extra expense, as it always does.

"And now that I've got my diploma, what am I going to do with it?" Chips asked herself scornfully.

But that her mother had meekly and eagerly denied herself everything to keep Chips in college was not what was annoying Chips most. Professor Salesby must not be forgotten. Or, rather, Professor Salesby must now be forgotten.

Professor Salesby was the youngest of the Wedmore faculty. He was a later Wedmore personality than even Chips, having been given the Eng. Lit. Chair at the beginning of Chips' junior year, but he had immediately become aware of Chips. For one thing she was one of the few girls who took his lectures with sufficient interest to think it worthwhile to arise and expostulate, and her keen comments were worth his attention. By the end of the second junior semester the girls were saying that Sonny-boy Salesby had quite a case on Chips, and during Chips' senior year everybody saw it.

They were not so far apart in years; it was not like the silly crushes goat-bearded old never-marrys sometimes get on coy young undergrads. In worldly wisdom Chips seemed even older than the gentle blond Sonny-boy, and she had twice his vim. She liked him. Her mind was as good as his and she enjoyed talking with him and seeing his mild surprise when she rather got the best of him in some argument. He was a little slow and rather too serious, but he had all the lovable qualities of a nice boy. It came to the time when his hand trembled when Chips smiled, and she was quite sure that she would go home after graduation with an engagement ring on her finger.

Sonny-boy may have thought so, too. The last formal event of the last day was the Class Dinner, followed by the sings on the steps, and after that was all over Sonny-boy came to Chips and they walked to the Frenshaw fountain and sat on the marble bench there.

"This won't seem like the same place without you, Chips dear," Sonny-boy said. "It is going to be hard for me to come back and not find you here."

"Yes; we've been good friends, haven't we?" Chips said. "It has meant a lot to me, knowing you so well."

"More than friends," Sonny-boy said. "Chips, there were times when I hoped -- you remember our Crashaw -- that you might be 'that not impossible she, that shall command my heart and me.'"

"Well, even that I should be the 'not impossible' is not impossible," Chips said with a nervous little laugh, and she hoped then that Sonny-boy would take her hand, but he did not. He leaned forward, instead, with his elbows on his knees as if he must say what he had to say to the gravel at his feet.

With his first words she knew it was not going to be an out-and-out proposal, but she could have borne with that if he had made it a mere plea for waiting. She was willing to wait. Heaven knew that young professors had to get their toes dug in before they shouldered wives! But he did not say, "Look here, Chips. I want to marry you, but we'll have to wait a while." That would have been fine. Nor did he even say, "See here, Chips. I love you, and all that sort of thing, but I'm not a marrying man." That would have been raw, but she could have forgiven that, too.

It was, Chips too unjustly told herself, a whine. There was a lot about his mother -- as if plenty of other young men did not have mothers to take care of -- and it was dreary stuff to listen to after the excitement of Graduation Day, the jollity of the Class Dinner, and the touching emotions of the last Step Sing of the whole class together.

"If he would just kiss me it would be something," Chips thought. "That would be something to remember, anyway." But it was evident he did not mean to do that, and in the very middle of his words she remembered that she had not ordered a taxi for the next day as she had promised Cassie she would. "Well, I can't just up and kiss you," Chips thought, and while he talked on, explaining that for the next hundred years or so he would probably be a slave chained to the wheel of education and be forced to live a life without love, Chips wondered if it was too late to order a taxi now.

For years and years, Sonny-boy told the gravel walk, he would not dare think of love. ("Well, that's reason Number One; I don't care to hear the other ninety-nine," Chips thought.) Duty must come first. ("My stars! What do you want me to do? Weep?" Chips asked him silently.) If, however, by any chance, the time did come -- ("Be reasonable! Be reasonable! A girl has to get some sleep!" Chips begged wordlessly.)

Even so, Chips was ready then to say, "At any rate, we part good friends," and she might have added, "and I'll always be a sister to you," with a laugh that would take away any sting. But Sonny-boy had to talk on, and it was when he came to his peroration that Chips' head went up and her fine nostrils expanded in a way that even Sonny-boy might have known meant danger, if he had seen.

"And so, Chips dear," he said, "I want to beg your pardon humbly for having -- well, taken up your time. For having let you see how much I did think of you. I shouldn't have done it. I was at fault and I do beg your pardon, humbly and contritely. You have been so strong, so maidenly, so sweet and good. I am ashamed of myself and the way I have acted. I have lacked the proper control of myself and I dare not even ask you to forgive me. Yes, I have been despicable and --"

Right there Chips jumped up from the bench.

"Why, you -- you worm!" she cried. "You miserable worm!"

Sonny-boy looked up then in amazement, but she was running toward Harley House, sometimes on the gravel walk and sometimes cutting across on the grass. She was crying with anger, and, perhaps, with something else, and she repeated again and again, "The worm! The insulting worm!"

Sonny-boy Salesby looked after her in a bewilderment of surprise.

Her words and her action had been most unexpected.

"Worm?" he said to himself. "Worm?"

He had thought he was doing something strong and manly, renouncing nobly something he desired, and making amends in a sublime way, and she called him a miserable worm and flew off in a passion!

When Chips found he was not following her, she slowed her pace to a walk. She was pantingly angry. She felt that she had never been so insulted in her life; he had called himself despicable for loving her when he should have cried out that it was the glory of his life -- if he meant anything at all -- and he had crawled in the dust like a worm. Much honor in being loved and thrown away by a worm!

Cassie, fortunately, was sound asleep in her own room next door when Chips came slamming in, and did not have to be talked to, and Chips got into bed, and, surprisingly, fell asleep instantly. It had been a strenuous day.

Cassie's parents had left on the evening train since Cassie had agreed to make one of those stop-off visits at Chips' home. Cassie's plans were vague. She thought she might try to get a job somewhere in the fall, something that had something to do with books, but there was a Jimmy Bland who might have a lot to do with her plans -- or might not -- and a week or two spent with Chips would be delightful. It would be pleasanter to break their long association with a lingering week or two of idleness together.

The shock that came to Chips was to find the inn closed. The sign on the door was "Temporarily Closed" and the door was locked, but a finger on the bell brought Martha Ann from the kitchen or some other rearward haunt.

"What's the matter? Is mother sick?" were Chips' first words.

"Miss Myra, your ma she jus' couldn't stand on her feets no longer," the fat cook said. "She jus' didn't seem able to get up this mornin' no way."

"How long has that been on the door? Take it down! Cassie, I'm sorry; I'll have to pitch in here. We can't have the inn close; it's our only income. I'll have to take charge of things."

"If you mean you are telling me I can chase myself away," Cassie said, "you can forget it, Chips. I'll love to help run an inn."

"Suit yourself; I'll love to have you stay. Martha Ann, is there food to serve if anyone wants dinner? Ice enough? Then make out a list; I've got to see mother. Come up, Cassie."

The mother choked back a sob when Chips threw herself on the bed to hug and kiss her.

She wasn't sick, she said, just tired. She hadn't seemed able to keep going; she had seemed to give out yesterday.

"My graduation day! Of course! You would drive yourself until then if it killed you, mother. You would see me through. I've taken down the 'closed' sign. Cassie and I will try to keep things toddling along until you're up."

"I just seemed to have to give up yesterday. I have tried so hard to please everyone, Myra, and some of them are so hard to please. This man --"

"What man?"

"I don't know who he was -- an automobile party of four. He complained the moment they were seated -- the chairs were too low -- and Milly brought cushions. Then the flowers had a vile odor. Then the food was not right. I apologized and apologized; and then the bill was outrageous for such food. I was humble, Myra -- we can't afford to drive customers away -- but he went out saying there was one thing he mighty well knew, he would never come here again. And then I just broke down."

"The hound!" Chips said angrily.

"It had been such a hard day," Chips' mother apologized. "I had thought about you so much."

"Now, stop! Stop!" Chips cried. "Cassie, she's begging my pardon for not being able to stay on her feet when she's knocked over! Mother, dear, please remember you are not my worm."

Milly, it seemed, had taken advantage of the inn's threatened hiatus to visit her family at Walbridge, and Cassie gaily donned an apron.

"I oughtn't to be such an awful dub at it," she told Chips. "I've seen enough tables waited on," and she accepted it as a lark. Chips was serious enough. Three small parties came for late tea and there were but six patrons for the chicken dinner which was the inn's specialty. Chips was in the kitchen when Cassie brought out a plate of chicken she had just taken in.

"He says it is tough," she told Chips. What do you do when the chicken is tough, and it is all the chicken there is?"

"It probably is tough," Chips said, "being ordered by phone instead of being personally selected. Was he mean about it?"

"Coldly haughty, rather," laughed Cassie. "'My girl, I cannot eat this, it is tough.' That sort."

"We'll try him with some other pieces," Chips said. "Martha Ann, which are tenderest?"

"Miss Myra, there ain't no tender to it; these chickens was born tough and got tougher right along."

"Put some on a plate," Chips ordered. "I'll take it in, Cassie." And she did. She carried it to the table where the complaining patron sat and put the plate before him. "I'm sorry," she said. "All the chicken is tough. The proprietor is ill and the cook did not have time to personally select tender chickens. Hereafter all food served here will be satisfactory, but as this is not, there will be no charge made for it."

"Well, really!" the man exclaimed. "But, I say --" And then he laughed. "All right," he said, "and I won't forget it. Thank you."

From him Chips went to the other diners with the same information.

"I did think the chicken was a little tough," one woman remarked. All, however, except the man who had complained, insisted on paying for their dinners, and the tips they gave Cassie were unusually liberal. They were, enough to pay for the complainer's free dinner with some over.

"You see, Chips," Cassie laughed, "it pays to be meek."

"Pays?" Chips burst forth. "Pays? It does not pay! It don't pay my soul, Cassie. I'm not going to grovel through life, lying down to be walked on, begging everybody's pardon, and being one of the world's worms. Tell Martha Ann to come here."

The black cook presented herself. She came doubtfully, not knowing what to expect.

"Miss Myra," she began apologetically, "Ah jus' couldn't do no better with them chickens --"

"Oh, stop it!" Chips cried. "I know you couldn't, and you don't have to get down on your knees and weep about it. Martha Ann, I think mother is all in. I think she's going to be sick, and if she isn't going to be sick, I am going to make her stay in bed and rest for a while. I am going to run this inn myself. I just want you to know it, and if you don't want to work for me you can quit right now!"

"Why, Miss Myra," the cook said, "Ah don' want to quit; Ah wants to stay and cook."

"Then you may stay," Chips said. "But listen to this -- you are a good cook; you are the best Southern-style cook I ever knew. This inn is going to have two specialties -- beaten bread for tea, and chicken dinners. You know what else, but only what you can do best. And everything has to be perfect. Perfect, you understand? No tough chicken; nothing that is not the best that anyone can get anywhere."

"Yes'm. Ah can have it that way," Martha Ann agreed. "That's how Ah likes to have it."

"And while you stay here, Cassie," Chips said, "I'm going to put you in charge of the dining room, if you'd like it."

"I'd love it," said Cassie.

"There's no telling how it will work out," Chips said, "but I'm afraid mother is through. I'll have to run the inn from now on. We can see in a week or two what comes of it, and if you like it and want to keep on, you will be my partner -- half and half, fifty-fifty."

"I wouldn't think of such a thing," Cassie said. "Not unless you let me come in respectably, Chips. If you will make an inventory I know father will give me the money to buy a half interest, and that's the only way I'll take half of the business."

"Maybe," said Chips, "when you know what sort of an inn this is going to be you won't want a half interest."

"What sort is it going to be, Chips?"

"It is going to be a self-respecting American inn," Chips said. "I'm not going to grovel for any man, woman or child or dollar on earth! I'm going to give good food, good drink, and good service for good money and hold my head up. I know how Martha Ann can cook, and I am not going to stand any kicking from chronic kickers, or crawl on my stomach to lick their shoes. And if they don't like it," she added inelegantly, "they can lump it. This is going to be one place where nobody has to grovel. And I mean you, too, Martha Ann."

"No'm," said Martha Ann. "Ah won't grovel 'less you says so."

The next day Chips had a painter take down and repaint the sign that had swung from the porch since her father died. The sign had borne the words, "The Friendly Inn, Teas and Southern Chicken Dinners," and in place of this Chips had the sign read "The Sauce Box, Teas and Southern Chicken Dinners." There was room beside the door for lettering, and there Chips had the painter put, "Our food and service are good. We permit no complaints."

"That's the sauce box part of it," she told Cassie. "It is time more people in America served good food and self-respect instead of bad food and cringes. Instead of good food and cringes, for that matter. It makes me so mad to see free and independent Americans behaving like frightened canary birds or whipped slaves. I'm not going to kowtow to any fat old overfed women or once-a-week automobile bounders. If they don't like the way I run this inn, they can go elsewhere for their tough chops and whining."

"But that 'We permit no complaints,' Chips," Cassie said. "You don't have to be quite so outspoken, do you?

"Don't I? This is the Sauce Box, I tell you." Chips laughed, "And they're going to know it."

She herself lettered the placards for the interior of the inn, and she made the letters large enough to be seen by a man who could read only the top row of an oculist's chart. One of them stated, "10% is an ample tip; less than 10% is petty."

"That's crude," Cassie ventured.

"No, it's not," Chips declared. "It's what we think and we're going to say what we think here. As long as I have Martha Ann in the kitchen and you in the dining room my soul is serene. I know I'm giving the best and I'll say what I please in the way I want to say it. I'm going to let people know that when they come here they come here for food and not for servility. Wait till you see the next one, Cassie!"

The next one was to be hung in the dining room. It said, "Our food and our service please us; if they do not please you there are other inns."

"I think that is a little forceful, Chips," Cassie objected when Chips showed her the rough draft. "Don't you think it is a little strong? Isn't it inviting them to stay away? 'Other inns?' Would you tell them there are other inns?"

"No, I wouldn't," Chips agreed, and she tore up the objectionable draft. She wrote instead, "If you don't like our food or our service you can get out and stay out."

"But that's awful!" Cassie exclaimed. "That's almost insulting!"

"It's meant to be -- to chronic kickers and those who want fawning. That's where the Sauce Box comes in," Chips said, and the placard went up as she had changed it. She had other placards, but not too many, and her first patron read them with a grin. He was a lone automobilist, a well fed, red-faced man, and before he got out of his car he honked his horn half a dozen times.

"That's the stuff, sister!" he said to Chips. "You tell 'em! And don't you take any of their back talk, either. I'll say it's a sauce box! Now, listen. Hurry my dinner up a little, will you? I'm in sort of a rush."

"We don't hurry," Chips said. "Dinner will take one hour."

"Then I guess I'll go and wash up," said the man with another grin. "You are the independent one, ain't you?"

So Chips lettered another placard: "This is not a quick-lunch counter. Our dinner takes one hour at least. We do not hurry."

In a week the Sauce Box and its sauciness were being talked about, usually with a laugh of appreciation and almost always with an added, "But they certainly do give you good food," and a "You ought to try it sometime."

Martha Ann made a small cake she called a "posie," shaped like a flower, and most delicious, and these, with the beaten bread, drew tea customers just as they had under Chips' mother's regime. The local women cared nothing about the Sauce Box's sauciness; they came and held their bridge parties at the Sauce Box. The fame of Martha Ann's chicken dinners spread, as word of good eating invariably does, and in order that passing automobile parties might not be disappointed Chips had a transparent and easily read illuminated sign set on the lawn so that she could change the wording by turning a switch from inside the house. "Dinner ready" was one of the things it said, but a turn of the switch could make it say, "Dinner ready; seats for four," or for one or for three or however many she had room for at the moment. And another turn of the switch made it read, "Dining room full. You'll have to wait." Before the end of July the firm of Chips and Cassie was able to have the exterior of the house painted and to put gay awnings at the windows.

Business rose to capacity and the veranda at the side was filled with tables, and Chips hunted up an adequate helper for Martha Ann. People, evidently, did not demand servility with their food. They were satisfied with cheerfulness. Now and then there was some slight trouble. A man who was somewhat intoxicated declared he had no napkin and he was just drunk enough to think it would be fun to make a fuss about it. He sent his waitress to find Chips, demanding an apology, and Chips made him stand up and search his pockets.

"Finish your dinner," she said when he drew out his handkerchief and the napkin crushed together, "but I don't want you to come here again."

Early in July the Sauce Box was doing so well and running so smoothly that Cassie decided to take two weeks to visit her home, which she had not seen since graduating from Wedmore. Chips' mother was recuperating splendidly and fretting to take charge of the inn again. Chips gave Milly temporary charge of the dining room and a few evenings later Milly came to her in the little box of an office at the rear of the hallway where she could keep an eye on the front door.

"There is a man at table six wants to see you, Miss Myra," she told Chips.

"Is it a complaint?" Chips asked, her head going up as she put down her pencil. "It is not six; no dinners are served until six."

"I don't think it is a complaint," Milly said. "He just said he wanted to see you."

Chips took up her pencil again.

"I am too busy to see anyone," she said. "Tell him politely that if anything is unsatisfactory we do not insist that he shall eat here. If it is anything else you can let me know."

"Yes, Miss Myra," Milly said, and went, but in a few moments she was back.

"Well?" Chips asked without looking up.

"The man at table six," Milly said, "says to ask you why you called him a worm?"

For an instant color flooded Chips' face. She dropped the pencil -- it fell from her fingers -- but she picked it up again. She had been checking over the afternoon's tickets and now she made a check mark on the one on top of the pile.

"Tell the gentleman, Milly," she said coldly, "that we serve nothing but our regular two-dollar chicken dinners after six P. M. Tell him we have no a la carte service. Tell him that if he wants anything not on the regular dinner card, whether food, drink, or answers to questions, there are other inns that will -- I'll tell him myself!"

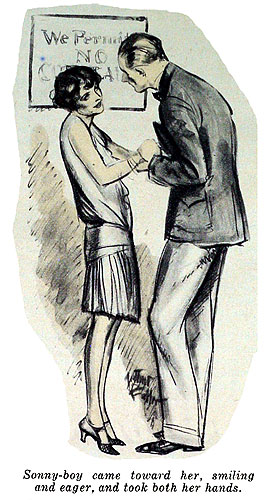

She pushed aside the tickets and pushed back her chair and pushed past Milly and went to the dining room. From the doorway she saw Sonny-boy, and when he saw her he came toward her, smiling and eager, and took both her hands.

"Well, Chips!" he cried. "Well, Chips!"

"Professor Salesby! And you found my inn!" Chips said, forgetting how distant she had meant to be.

"I found you," he laughed. "I came the first moment I could; wiggled along -- or was I an inchworm, Chips? They hump themselves, don't they? Why did you call me a worm?"

Chips drew her hands away. He had been holding them altogether too long and tightly even though Milly industriously kept her back turned.

"I called you a worm," Chips said, her chin in the air once more, "because that is just what you were. You cowered and cringed and -- and --"

"Whined?" suggested Sonny-boy.

"And whined."

"Very rare new variety, the whining worm," Sonny-boy said. "Found only in chairs of Modern English in colleges --"

"No, found everywhere!" Chips declared. "And it makes me so furious, so angry! It obsesses me, and I can't help it. It makes my blood burn to hear everyone begging, 'Please, will you forgive me for living? Please, will you forgive me for serving? Please, will you forgive me for loving?' And you literally got down in the dirt at my feet and --"

"Whined?" suggested Sonny-boy.

"Wept -- almost wept," Chips said.

"I felt like weeping," he told her. "I was a coward --"

"There! You see! You're beginning again. How can a --"

"I was only going to say I was a coward not to weep like a child if I felt like weeping like one," he interrupted. "A brave man should do what he feels like doing. What I am asking you is why you called me a worm?"

"Why, I've just told you --"

"You've told me why you thought I was a worm," Sonny-boy said. "You haven't told me why you called me one."

"Why I called you --"

"Why you jumped up and shouted it at me -- 'worm' and 'miserable worm' -- and went raging through the night like a fury."

"Professor Salesby, I don't have to answer --"

"Chips, you're just as much in love with me as I am with you, and I never guessed it. I never would have believed it if you hadn't gone storming off, shouting worms at me. You hurt me, Chips. I was sorely wounded when I dragged myself home. I didn't sleep that night. And then one day -- I'd gone home -- the truth occurred to me and I sat down and laughed and laughed and --"

The indignation of Chips was spoiled by a party of six that filed into the dining room.

"The Sauce Box, hey?" laughed the jovial fat man at the head of the party. "I'll say so! Look at that sign -- if we don't like it we can get out and stay out. That's the spirit! That's the way you talk to me, Jessie. Well, I'll bet we get a good meal here."

"We can't talk here," Chips said. "Come into my office, Sonny-boy."

Half an hour later a man named Tenker with his wife Louisa and a friend of theirs named Brownlee and Brownlee's wife went out of the door of the Sauce Box and Mr. Tenker slammed the door behind him angrily.

"That's what I call rotten," he grouched. "I'll never come here again. Look at that sign there -- not changed yet -- 'Dinner ready, seats for four' -- and when we go in there's no room, not a seat, and out we come, hungry."

"That sort of thing gives a man a pain," said Mr. Brownlee.

"Yes, but she apologized humbly enough," said Mrs. Tenker. "She begged our pardon plenty, Joe. You heard her, Emma; she said she was sorry but something had happened to make her forget to change the sign."

Even as Mrs. Tenker was speaking the illuminated sign changed to "Dining room full. You'll have to wait."

"Yeah!" said Mr. Tenker scornfully; "I saw a fellow kiss her when we went in. Where'll we try next, Sam?"

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 2:59:37am USA Central