|

|

from Woman's Home Companion

The Chromatic Ghosts of Thomas

by Ellis Parker ButlerOur cat Thomas was very sensitive. I never knew such a sensitive cat as Thomas was. The slightest harsh word seemed to hurt his feelings and put him into a fit of the dumps. And if anybody scolded him he would sob once or twice, then burst into tears. My wife and I tried to be gentle and kind to Thomas, but when a cat has such abnormally sensitive feelings as that, one is almost every minute doing something inadvertently to wound them, and Thomas seemed to be everlastingly looking for something to take to heart. It got so that he wandered about the house from one week's end to another, with a downcast, mournful expression, and it began to get on our nerves.

Time and again I made up my mind to speak to my wife about it, and then I would remember how kind and loving and faithful Thomas had been when he was a kitten, and I would try to soothe my nerves by playing on my violin; but whether it was the material of which the violin strings were made, or something else, this would hurt Thomas' feelings, too, and he would sit and look at me, oh, so sadly! until I would have to weep also, and then my wife would come in, and seeing both her darlings in tears, would fall to crying. We were very, very unhappy, and all because Thomas was so ridiculously sensitive.

I stood it until one day when he had been more than usually moody. He had taken offense at some fancied slight early in the morning, and all day he had sat with a frown on his brow, not saying a word to me, nor answering me when I spoke to him, I said nothing until evening, and then, being sure that Thomas had fallen asleep on our best silk damask chair, I spoke to my wife about it. I told her plainly that I was becoming a nervous wreck on account of that cat's feelings. I said that either I would move out and leave the house to Thomas, or that Thomas must move out and leave the house to me; that his moods were too moody, and that his permanent melancholy was beginning to tinge my writing, and that if I lost any more of the blithe joyousness that was my principal hold on the public, I would lose my popularity, and no one would want my writings, and we should all starve.

I can see now that I was a little too vehement. My mind was very much wrought up over the matter, and I may have spoken louder than I had intended. At any rate, Thomas suddenly jumped from the chair and walked dejectedly from the room. At the door he stopped and gave me one reproachful glance, and then we heard him push open the screen door and go out onto the kitchen porch.

My wife and I sat for a minute in silence. The awful significance of what I had done came upon me. Never before had I outspokenly told my feelings regarding Thomas in his hearing.

"Edward," said my wife, "I fear you have mortally offended Thomas."

I pretended I was indifferent about what Thomas thought of what I had said, but at heart I was worried and ashamed. I knew I had said more than I had intended. In the heat of my words I had gone further than I should otherwise have gone. However. I doggedly set my mouth into firm lines, and scowled.

"Edward," said my wife anxiously, a few minutes later, "Thomas is very quiet out there. Don't you -- don't you think you had better go and coax him in? Hadn't you -- hadn't you better go to the door and say a kind word to him? You know how sensitive he is, and --"

She did not say the awful words, but we both understood what she meant. Thomas was in the exact condition of melancholy in which suicide suggests itself to the hypochondriac mind. I moved uneasily in my chair. I hated to beg the cat's pardon, for I felt that I was right in the quality of what I had said, even if I had made the quantity too large. I hesitated, and then I rose.

At that moment my wife screamed, and I -- strong man though I be -- jumped nervously, for our straining ears caught the sound of a heavy body splashing into our rain barrel. For one terror-stricken moment Mary and I stood looking at each other aghast; the next moment I was dashing from the room. Wildly, impetuously, I ran to the rain barrel. Our worst fears had been realized. Thomas had committed suicide!

My garden rake was standing near, and with it I hastily raked all that remained of poor, misguided Thomas out of the rain barrel, and laid his dank body on the back porch. Poor Thomas!

Mary came and stood beside me, and I threw my arms around her, and together we looked down at that dripping, lifeless form. When her first strong paroxysms of grief were over I took her hand, and then, as we looked, Thomas quivered, staggered to his feet, and tottered into the kitchen. You may be sure that Mary and I were joyful. We got a huckaback towel and rubbed him dry. We dosed him with hot catnip. We stroked him gently, and tickled him under the chin, where a cat loves best to be tickled. He revived quickly, and, strange to say, he seemed to bear me no resentment. In fact, he seemed to be a new cat. He had no recollection of what had passed between us, nor of his awful act. He was happy and blithe, as he had been when we first made his acquaintance, and he purred and smiled at us good-naturedly. We left him asleep by the kitchen fire, and Mary and I went into the parlor to talk the matter over.

We decided we would be very good to Thomas in the future, for his suicide had been a lesson to us, and we knew that Thomas had only eight lives more. No cat has more than nine lives at the best, and we agreed that we must do all we could to cherish those eight remaining lives. We sat in the parlor planning pleasant little surprises and gifts for Thomas, and evolving new ways of making him contented and happy, for we felt that our little home must be dull for a cat of Thomas' parts, with no children to amuse him, and we saw that we had been wrong to blame him for his melancholy. We should have made his life pleasanter and brighter, and should have tried to draw him out of himself more. So interested did we become that we were surprised to hear the clock strike midnight, for time goes so quickly when one is conspiring good deeds.

As the last stroke of twelve sounded Thomas bounded into the parlor. His eyes were glaring wildly. His limbs were trembling. Every hair on his body was standing erect. He backed between my feet, and stared with horror at what seemed to us to be but the vacant air. He alternated between pitiful mewing and frantic spitting and clawing at the air before him. I supposed that he had awakened suddenly out of a bad dream, but when I bade him go to his usual bed in the kitchen he plead so piteously to be allowed to sleep in our bedroom that Mary begged me to remember how near we had come to losing him. and I agreed to let him come with us.

The permission seemed to give him pleasure, but all the way up the stairs he kept close to my feet, now and then looking back with evident terror, and while I was disrobing he did not move an inch away from me.

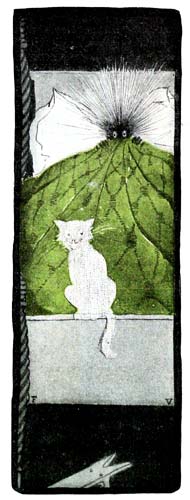

When I turned off the gas and moved toward my bed. I stopped short in amazement. In the black darkness of the room I could distinguish Thomas by his two huge, terror-stricken eyes, but that was not what made me pause and tremble. Perched on the foot of my bed was a thin, phosphorescent form. It was a pale blue, transparent cat, and its face was contorted into a diabolical grin. Through it I could see the frightened face of my wife. In every feature the ghost cat was identical with Thomas. It was, indeed, the ghost of Thomas' first life returned to haunt him. I do not -- or did not then -- believe very much in ghosts. I have always been willing to admit that there were ghosts, but that a man of any stamina should be afraid of them seemed to me the utmost folly, and I took a hairbrush and tried to brush the blue cat ghost off the footboard of my bed, but the ghost cat would not vanish; the brush passed through it as it would have passed through a moonbeam. I blew at the ghost, and it flickered, as a flame flickers in a draft, but it remained where it had been. If anything, it glowed with a brighter blue.

Thomas had jumped upon the bed and was cowering in my wife's arms. My own hair and my mustache were standing erect, and the hairs of my mustache tickled my nose and made me sneeze repeatedly. I sneezed right through the cat ghost each time, and this bent him into odd curves, twisting his infernal grin into horrible caricatures of Thomas' sweet face.

I tried every antidote for ghosts of which I had ever read, but without the least success; and finally I lighted the gas again, which dissipated the cat ghost so far as Mary and I were concerned. I thought I could see a thin blue haze above the footboard, just where the cat ghost had been.

To Thomas, however, the blue ghost remained perfectly visible, as we knew by the manner in which he trembled all night as he lay between Mary and me. I was very thankful that he was a cat instead of a pig. for his hair remained permanently erect, and if he had been a pig his bristles would have stuck out like those on a hairbrush, and would have made sleep impossible for us.

I hoped that the ghost cat would depart with the rising of the sun, but although to Mary and me it was quite invisible, the actions of Thomas told us as plainly as possible that the ghost of himself was still haunting him. All that morning Thomas walked sideways, spitting and scratching at the thin air where we knew the ghost cat must be walking beside him, and occasionally he would make wild dashes around the room, or seek to climb the smooth side of the hall, or hide his head under a hassock. As the day wore on he became exhausted, and he finally fell into a troubled sleep. He slept several hours, until about nine o'clock in the evening, and then he awoke with a blood-curdling scream, and dashed madly up the stairs.

My wife and I darted after him, but we were too late to save the rash creature from the consequences of his folly. As we panted into the attic we saw him dash madly through a pane of glass in the window under the eaves, and a moment later we heard him strike on the brick walk below. Poor, poor Thomas! Once more he had been driven to that last resort of unfortunates, and had killed himself. I threw my arms around Mary, and when her first strong paroxysms of grief were over I took her hand and together we wended our way downstairs and opened the door.

There was a dogged look as Thomas entered the hall -- a look of hopeless, spiritless woe that was only broken when he sprang, striking out viciously, at the ghost, now to one side and now to the other.

I thought it best then to speak to Thomas as one man should speak to another. I told him that he was not playing the part of a man; that he should bear up and be brave; that men had been haunted by ghosts before, and had lived to be happy, and that he should try to conquer his hatred and fear of the blue ghost, and bear with it; but Thomas only crept closer to Mary's skirts, and refused to be comforted or to have his fears allayed.

That night a second ghost of Thomas took its place on my footboard beside the first. There was no question then that Thomas had lost the second of his nine lives, and that he had but seven left, and before I got into bed I gave him a good lecture on the necessity of taking good care of the few precious lives he had left. But his attention was not on what I was saying; and that can hardly be wondered at, for the second ghost on my bed was as like the first as one pin is like another, and both were as like Thomas as could be, but the second ghost was, instead of being blue, a rich, vivid red.

The two ghosts prowled back and forth, walking through each other, and if I had not been possessed by a shuddering chill I should have been highly amused, for when the two ghosts walked through each other, and the red and blue combined, they formed a rich purple. I might with honesty say that I had never seen a blue cat ghost before, nor even a red cat ghost, but I can take my oath that neither I nor my wife nor Thomas had ever seen a purple cat ghost. It was trying for me and for Mary, but think what it must have been for Thomas, considering that these were ghosts of himself.

I will not extend this story needlessly. Any one who wishes to read the complete details will find them in the report I wrote for the Society for Psychical Research. I cannot, I fear, make the story as amusing as it would be if it were a work of fiction. It would be amusing, no doubt, were I to go on to say that each night a new ghost of Thomas was added to the line of ghost cats that prowled about on the footboard of my bed, until nine ghosts of various hues were gathered there. Mr. John Kendrick Bangs would doubtless have sacrificed the truth in order to create just such a comical situation, for he is a humorist, and if a few vari-colored cat ghosts had happened to roost on his bed, he would have seen something funny in them, and would have exaggerated the facts in order to have a little fun with the subject; but I have a reputation as a family man and as secretary of the Bowne Park Improvement Association to maintain, and I cannot bring myself to pander to your love of amusement by any such mendacity. I must stick to the facts.

Of course I cannot deny that poor, dear Thomas committed suicide every day for nine consecutive days; for that is the truth. In spite of all our efforts to prevent him, he managed each day to accomplish his fell purpose.

I cannot deny that on the third day he ate an abnormally large portion of rat poison, driven to desperation by the care that kills cats, nor that when, after Mary's first strong paroxysms of grief were over, Thomas staggered up our stairs with only six lives remaining in him, there was a new ghost on the footboard to greet him. Neither can I deny that when, on the fourth day, melancholy seized him, and he jumped into the oven of our gas stove, when the heat there was as great as is obtainable from our suburban gas, and perished miserably, my Mary was seized with a paroxysm of grief, for we loved Thomas, and it pained us to see him get into the dying habit.

Nor shall I deny that he died by his own act on the fifth day, when he allowed our heavy front door to slam shut on his neck, extinguishing himself and causing my wife strong paroxysms of grief. And it would not be the truth if I did not say that on the sixth day Thomas, to the paroxysmal grief of my wife, chewed up and swallowed a lamp chimney, and died a wicked death. I trust, too, that my wife is as tender hearted as any other woman, but I cannot deny that when, on the seventh day, we found Thomas hanged by the neck in our lovely three-dollar-ninety-eight-marked-down-from-five-dollar rope portieres, and dead. Mary's paroxysms of grief were less strong than Thomas had, perhaps, come to expect on such occasions. I claim that no woman can be expected, by any reasonable cat, to keep up a high standard of paroxysms of grief day after day without falling off a little in energy from time to time.

But Thomas was not a reasonable cat, and what he thought was Mary's indifference so affected him that on the eighth day he gnawed the rubber coating off an electric-light wire, and perished miserably. My wife hardly paroxysmed at all. But it was another matter when, on the ninth day, poor, dear Thomas snuffed out his last life by crawling under the sofa pillows of our almost Oriental cozy corner, and there suffocated. Then we knew poor Thomas was indeed lost to us. While six or four lives are left there is still, as the proverb says, hope; but when the ninth life of a cat is gone, it is a dead cat. Our sweet, suffering Thomas had left us, and I cannot deny that when Mary had recovered somewhat from her paroxysms of grief we hoped we had seen the last of Thomas. These things I cannot deny; but at no time was our bedroom full of multi-colored ghost cats, walking through each other and perching all around the room. We had no such vision of a woe-begone Thomas mournfully moving about the house followed by his eight ghosts of himself in a long, prismatic row.

What really happened was this: On the third night a third cat ghost of Thomas appeared, of a rich yellow color, and perched on my footboard, but the red and blue ghosts of the night before had permanently merged into one ghost of a rich purple. I do not try to account for this. I merely state it as a fact, and say that any one who knows anything about color knows that red and blue combined make purple. On the fourth night the purple ghost and the yellow ghost were joined by a new blue ghost, of a rather stronger shade than the first blue ghost had been; but when a red ghost appeared on the fifth night we found that the yellow and blue ghosts had combined to form one green one, and then this red ghost and the green ghost amalgamated into one brown one.

Thus it continued, a new yellow cat ghost materializing on the sixth night, only to mingle with a new red one on the seventh night, making a lovely orange-colored one; while on the eighth night a most peculiar cat ghost appeared that was what might be called a tortoise-shell cat ghost of all hues. We went to our room on the ninth night with considerable anxiety, not knowing what the last ghost of Thomas would be like; but we found that all the ghosts had combined to form one single ghost of spotless purity -- a white iridescent ghost with a white iridescent grin that faded away into the air and disappeared entirely.

Perhaps truth is stranger than fiction. Perhaps you may consider this blending of the ghosts stranger than the congregating of nine prismatic cat ghosts would have been. I can only say it is more logical.

For several days after Thomas for the last time left us so abruptly -- cut down for the ninth time in his prime -- my wife and I discussed the matter, but we could make nothing of it, and it was at her suggestion that I wrote out the whole story and laid it before the Society for Psychical Research. The conclusion that the society reached was that in this the laws of ghosts was happily illustrated; for if every cat was allowed to send nine distinct ghosts into the ghost realm the population there would soon be too cattv.

It was also pointed out that if each ghost of poor, dear Thomas had been white, each would have been complete in itself, but that by being colored they could only reach perfection and harmony by combining to form one white ghost. The society also asked us to let it know if we were haunted by Thomas in his new and white form; but we have had nothing to report. Occasionally we awake at night to hear a soft patter of feet, or a weird rattle of plaster in the walls, or unearthly squeakings, but while I am persuaded that these are due to the death of Thomas, I do not believe they are ghostly manifestations. I know they are rats.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 1:22:24am USA Central