from Appleton's Magazine

I Gae Doon the Doone Dune

by Ellis Parker Butler

I believe it was Epiphany morning, or somewhere about that period, with Lorna locked into the terrible Doone Glen by the great snow that had never ceased for nights, and all the earth topmost hedges covered, the kitchen thawing my goose-grease (being subject, I suppose, to croup at night), and wondering how she fared, my sweet Lorna, at the hands of Carver Doone and those other rascally Doones, now that the snow prevented me entering their valley, for had I attempted it I should have been engulfed and lost in the snow, as I am always getting lost in these great sentences of mine (for I am indeed but a simple fellow, despite my six feet seven and enormous strength), and I mourning that I could not take Lorna a mince pie and a few eggs, when Lizzie ran into the kitchen to me.

"You great fool, John Ridd," she said, being always a pert little creature and too much given to bookish reading, as I thought and do still think; "you great fool, John," she said, "what a pity you never read, John!"

Now I would fain have boxed her ears, it not being the custom for honest farmer-men to read books in the Exmoor country in the year 1690, but she made care not to approach too nigh.

"Now, John," she said, knowing whereof I was thinking, "think of poor Lorna, with never a pie, perhaps, nor an egg, and I almost frozen in bed last night; and Annie like an icicle. Now, will you listen to climates ten times worse than this, John?" Then she told me all she had read regarding the Arctic regions, as they call some places a long way to the north, where the great bear lies across the heavens, and no sun is up for whole months at a time, and yet where people will go exploring, out of pure contradiction and love of being frozen -- that there they always had such winters as we were having now. But what most caught my attention (simple as I may be) was that the people there (although the snow was fifty feet deep, and all their breath fell behind them frozen, like logs of wood) managed to get along and make their journeys, by a little cleverness, for they contrived a way to glide like a flake atop of the snow, with a sort of boat on each foot. And this was the first I had ever heard of such a thing, but Lizzie told me how these foot boats were made, as well as she could remember it; very strong and very light, of ribs with skin across them, five feet long and one foot wide, and turned up at each end as a canoe is.

Never had an honest farmer of Exmoor, whose business is sheep, thought upon such things as these snowshoes, but upon that hint from Lizzie (for I am but a simple fellow) and with old John Fry to aid me, I set upon building for myself and John Fry each a pair of strong, light snowshoes. Seven feet long and one foot wide I counted to be great enough for old John Fry, he being but an ordinary man, but I would not trust my great body upon any such, and soon made myself a pair, framed with ash and ribbed of withy, with half tanned calfskin stretched across, and an inner sole to support the feet, twelve feet long and of a width of two feet.

"Merzy o' God!" cried old John, when he saw these snowshoes complete and I at last told him what I meant to do with them; "watt a vule thee must be then, Jan, and myzell no better. Go zober, lad, go zober!"

In vain did I explain to him how the Arctic men glide like a flake atop of the snow, and tried to give him some part of the enthusiasm with which I was filled.

"It baint to raison, Jan," he declared with a wry face; "but it baint for me to argify. If thee wants to goo, goo then. Jan Vry wants none o' thiccy znowshoon."

"Hold thy tongue, John Fry," I said. "Go I will, and go you must, for my poor Lorna may be being murdered, and I must take her a mince pie and a dozen good eggs, so gird your snowshoes on thy feet and we will be off."

Thereupon I rubbed my legs well with neatsfoot oil, and attached the snowshoes to my feet, and took in one hand my staff, and in the other the mince pie that Annie had made, and that I had kept since Twelfth-day for Lorna, and under my arm a great loaf of brown bread, hollowed out and filled with a dozen eggs. But as for John Fry, he carried but his staff and his blunderbuss, for never would he have ventured near Doone Glen without that latter, well loaded with nails, screws, and bits of broken crockery, rammed down atop of a good fat charge of powder. But now that I had the snowshoes on my feet I found great trouble, as one must whose toes turn in, be it ever so little, for whichever foot I put down first I found the other snowshoe standing atop of it, like one ladder laid across another, so that in whatever direction I stepped I fell over in that direction, and indeed often I found John Fry and me with all our four snowshoes standing one on the other and ourselves toppling hither and yon into various parts of the barnyard.

However (albeit I am but a simple fellow) I guessed rightly enough that the bare ground of the barnyard was no place to wear snowshoes, which are meant to glide like a flake atop of the snow. Now I was sorely put to it to know how to get atop the snow, for I had cleared good paths all about the house and barns, with tunnels in places, and the sides of the paths were like great walls of snow, and how to climb these walls with fifteen feet of pigeon-toed snowshoes on my feet and a staff and a mince pie, and a dozen raw eggs in my hands, gave me worry, until I thought of going to the upper floor of the barn, which was not much more than on a level with the snow, and I should never have thought of this (being but a simple fellow) had I not happened to think of it.

Therefore I went up into the barn, with John Fry snugly tucked under my arm (for he seemed strangely reluctant to set out upon this journey), and when I threw open the hay door the great spread of snow lay below us ready to be glided over like a flake.

I thereupon bade John Fry to step out and glide, but he hung back until I gave him a gentle push in the back of the neck with my staff, whereupon he descended to the snow like a bird. I say like a bird, for whether it was because I pushed his head first (being but a simple fellow), or whether it was that the snowshoes, being the lightest part of him, naturally arose to the top, he went flying, with his great snowshoes beating the air like the wings of a bird, and fell head first into the great depth of snow, so that I thought I had seen the last of good John Fry. But in this I was mistaken, for when the whole of him was gone but the snowshoes and they reached the surface of the snow, they stopped there, being so built as not to sink into it, but stayed atop of it like a cork atop of the water. With this I was delighted, for it proved indeed that there was something in Lizzie's idea of snowshoes.

As I looked John Fry began to kick, as a man will when he is head down in a snow bank, and I observed that each kick was like to a step forward, carrying him in the direction of Doone Glen, albeit upside down and slowly, all of him being beneath the snow but the snowshoes. Whereupon I was mightily pleased, for he was, when right side up, an endless chatterer, and so long as I must take him with me I preferred him upside down.

Now, I am but a simple fellow, but I conceived that the position taken by John Fry was not the proper one in which to glide like a flake atop of the snow, and I resolved to take a different position, and upright, with the snowshoes at the bottom, and thinking of Lorna the while, I stepped from the hay door.

I see now that I should not have been standing on the fore rigging of my right snowshoe when I made that step, for I made the descent in the form of one fourth of a circle, my head leading the way, and the snowshoes bringing up the rear, and in this manner I continued down into the snow until my snowshoes lay flat atop of the snow.

Now, there may be many things to do in such case, but I am but a simple fellow, and my mouth was full of snow, and as none of the many things came to my mind, except to kick, I kicked. At first I kicked with a sort of wild tumultuousness, merely to accomplish the act of kicking and to relieve my soul, but I soon saw that I was moving through the snow, and I regulated my legs to an even, systematic kick that carried me well forward at each kick, and therein I was wiser than John Fry, who was kicking in a catch-as-catch-can manner or, as I may say, trying to get in as many kicks per minute as possible, which is poor policy in a long-distance race. And in this I was borne out by the fact, for I soon heard the muffled sound of a voice cursing as only John Fry can curse, and I knew he was traveling in the same direction, albeit on a course a little to the southeast, and by kicking a little harder with the left leg and backing water with the right I soon came upon him.

"John Fry?" I said, as I reached him.

"Raight 'ere, oopzaide doon, and raight glad t'zee ye, lad, tho' I baint able t'zee ye at all," he said. "Fash me, 'tis zo hard trarvelin' oopzaide doon I was in doubt 'twas the raight way t' trarvel wuth znowshoon. Do thee trarvel oopzaide doon, lad?"

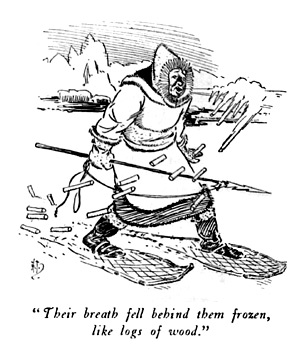

"I do, John Fry," I said, for it was not proper that I should let him, who was but an underling, know I was not traveling as I wished. "And with the wind in this quarter we will make the Doone Glen before the thaw, John Fry."

"Merzy o' God, Jan," he cried, "ye'll no gae doon th' Doone dune oopzaide doon, wull ye? Vamous job this 'ere! Veel laike a ztern-w'eel zteamboat, lad, if siccy thing invented yet, but ut baint, zo don't knaw whut I veel laike. Not t' zay ztern-w'eel zteamboats trarvel oopzaide doon, Jan."

"Save your breath, John Fry," I said sharply, "and take hold of my staff, and I will take the lead."

With that we were under way again, and made good speed, though, in truth, to anyone looking down from above it would have been a curious sight to see my great snowshoes kicking along over the surface of the snow with John Fry's smaller ones flopping along behind them, twenty strokes to the minute. Nor would I cast ridicule upon John Fry, for often during that journey I envied him his smaller stature, when we came to shallow places in the snow and my head dragged along the ground or grazed the tops of stumps. There was one great stretch where my head bumped bottom at every kick, as if I were hopping along on my head, while John Fry, being of lesser draught, sailed with an even keel above all.

We were thus proceeding with good speed, myself a staff-length in advance, but with John Fry beginning to show weariness in his legs, when my face came briskly in contact with some hard, rough object, taking the skin off my nose. By rubbing my face against it I judged it to be a sizable tree, and I deemed it well to mount it and take an observation, and I wrapped my legs about it, with an intent to thus shin up it. Now, I had never in my life shinned up a tree upside down, and it cannot be done without the use of hands, as I soon discovered, but when I tried to unwrap my legs from around it I found I could not, the toes of my snowshoes being locked together. Then I was fain to believe I must remain there until spring, with my staff in one hand and the mince pie in the other, and the loaf of fresh eggs under my arm, and I was thankful indeed I had brought the mince pie and the eggs. For I saw, clearly enough, although I may be but a simple fellow, that when the eggs and pie were gone I would have my hands free, and could then climb the tree, but that, had I not brought the eggs and pie I should have starved before I had eaten them and freed my hands.

I was hanging thus, and just lowering the pie to the neighborhood of my mouth, when John Fry kicked up alongside, and I explained the precarious position in which I found myself.

"Doon't 'e be a vule, Jan Ridd," he said (words for which I trounced him well when all these dangers were over). "Wutt be 'bout, lad? God's zake, want break thee teeth? Doon't 'e bite siccy pie; hand ut me, Jan! "

And I did as he told me, for I knew well that eggs and pies meet to be taken upon such adventures must be, indeed, strong, durable ones, and not such as men should venture their teeth upon. I handed him the eggs and the pie and my staff and shinned up the tree as well as might be, with small adventure except the getting of my snowshoes tangled in the branches of the tree, and then, reaching down, I pulled John Fry up and tossed him lightly into another tree that stood near. And now a wonderful sight met our eyes, for we were upon the very crest of the hill overlooking Doone Glen and all that valley was one white cup of snow, and afar off in it I saw the little mound of snow that I knew must be my Lorna's cot, and beyond that the other Doone cottages. So I told John Fry what I meant to do, which was no other thing than to make one jump down the hill, or precipice, into the Doone Glen, and he also. But he looked at me mournfully from the tree where he was hanging rather loosely by the feet.

"If 'e zay so, Jan," he said sadly, "why, joomp I must, but my laigs be 'boot kicked off, lad. Baint used to siccy zwimmin' in znow, laike, oopzaide doon; I be plain farmmersman, oosed to trarvelin' raightzaide oop. Doubt 'twull kill me, lad!"

"Silence, John Fry," I cried. "Be sure it would kill you were you to jump without your snowshoes, but to light on them will break your fall."

"Zo far, lad," he said mournfully, "I be no hand laightin' headzaide oop. Larst taime I laighted znowshoon up. If 'e doon'ty care, Jan, I wull zwim in th' znow. 'Tis no siccy bad fun zwimmin' oopzaide doon. Man gets laikin' ut aifter a bit. I zort o' got th' habit, lad. I wull zwim doon."

"No, John Fry," I said firmly, and so that he could not misunderstand my meaning, "you will jump down!"

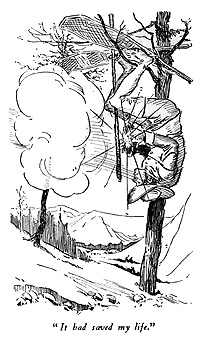

At this he got himself into such an unreasonable passion as I never saw and, from where he hung in the tree opposite me, he threw the mince pie at me with all his might, and might have killed me, had it not, as it came whirling with its fluted edges revolving like a buzz saw, struck a tree limb. As it was, the pie cut the tree limb short off and sawed a slot in the tree trunk back of me, where it stuck. And then I did a thing that I might long have regretted (though, as you shall see, it proved my salvation), for I grasped the pie and was about to throw it at John Fry, killing him, when it slipped in my hand, and while I held it against my breast, getting a firmer hand grasp upon it, John Fry raised his blunderbuss and fired full at me. For an instant I could not imagine what had happened, but the rattling of nails, screws, and broken pottery against the pie told me it had saved my life. Nor was any harm done the pie, save a few slight dents and scratches in the upper crust. It remained as edible as before. Nay, more so.

Although I now had this formidable weapon in my hands John Fry still had the twelve fresh eggs, and I knew (albeit I am but a simple fellow) that eggs such as a man would take upon such a jaunt must be formidable weapons not to say petrified, but, perchance, what we call nest-eggs or china door knobs. I therefore reached over with the toe of my right snowshoe and wiped John Fry out of his tree, and he went head first into the snow, as I had intended, like a cork into a bottle.

I now bethought me that I must be on my way, and that, in his present state of mind, John Fry would not be a proper companion. Yet, not wanting him to stray, I reached down and removed one of his snowshoes, whereat he kicked angrily, but it did him no good, for with but one shoe he but revolved in circles. And in doing this I had another thought, which was of the mince pie, for I dreaded to make the leap with anything so dangerous in my hands, lest I destroy myself, and yet I dared not cast it down the hill, lest it disappear in the snow, and I appear before my dear Lorna pieless. I therefore bound the pie firmly upon John Fry's snowshoe and cast it down the hill, and it alighted upon a bank of snow, and lay there as calm as a summer's eve.

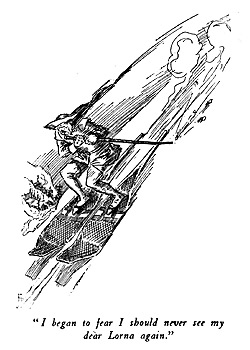

Now, when I had done this, I untangled my snowshoes from the tree, and balanced myself upon a dead limb, and made a mighty leap out over the edge of the hill. Then the air vibrated through the withy pieces and the calfskin strips of my snowshoes like a violin as I fell, and at times I was one end up, and at times another, and at times I seemed to be both or neither, and I could only hope I might light snowshoes first, which, by good fortune, I did.

Yet was my journey no nearer an end, for no sooner had I struck the elastic surface of the snow with my flexible snowshoes than I was up and away again, in spite of myself, like an arrow from a bow, sailing through the air, nor can I tell aught of what I did until I alighted in a tree, and then, by looking around, I saw I was upon the hill on the opposite side of Doone Glen than that from which I had started, having traveled as does a rubber ball that one throws to the floor at a goodly angle. So there was nothing for me to do but jump once more.

Now no better luck followed me this time, for I again alighted upon my snowshoes, and again soared away, back to my original hill, but I am not one to be easily discouraged (albeit, or perhaps because, I am but a simple fellow), and I continued to jump down those Doone hills and bounce up again, hardly alighting until I was under way again, and hardly under way until I had again alighted. For I hoped some time to alight upon my head, that being of a solid, unbouncing quality, but as time went on I began to fear I should never see my dear Lorna again, or at least not until the sun had melted the snow, or my snowshoes wore out, and great tears came into my eyes to think of her, in her cottage, believing me, perhaps, unfaithful to our love, while I, for days and weeks, bounced from hill to vale and from vale to hill again. Nor was the least of my fears that Carver Doone might spy me out and shoot me on the wing.

But the second day, about the tenth hour of the forenoon, when I had jumped for the three hundred and tenth time from my original hill (making six hundred and nineteen jumps in all), and was on my way down, I saw a sight that filled my heart with uttermost fear and distress, for directly below me, and where I was bound to alight, lay the mince pie I had cast there the day before. Now I knew not what I should say to Lorna if I was obliged to go to her without some article of food with which to open the conversation, and yet I saw no way to avert landing on that pie. And yet it all proved for the best.

For I did alight upon the pie, and although the impact was such that my feet were so benumbed that I could not stand upon them for many minutes, there was a consistency, or constitution, about that pie that was far from resilient, and I did not bounce into the air. And as for my fears regarding the destruction of the pie, they were quite groundless. It was bent, but it was not broke.

Having set myself aright, and being in good spirits, I made boldly across the valley, being now afraid of nobody, and when Lorna and Gwenny heard my knock at their door, they threw it open, and fell weeping upon me, or so I supposed, for the tears stood in their eyes, and their eyes were red. But I soon learned that they were barricaded against Carver Doone, and were forced to get heat from an old wreck of a cook stove, out of a hole of which, where a stove lid was missing, the smoke could not but pour. But when I drew my mince pie from my jacket and handed it to Lorna, she first gave a glad cry, and then stood on tiptoe to give me a kiss, and then ran and laid the pie in the place of the missing stove lid.

"Your dear old John," she cried, clapping her little hands; "see! it is a perfect fit!"

"An' noo lakly t' brak," said Gwenny.

And now, having comforted Lorna, and arranged with her for her flight from the Doone Glen, I donned my snowshoes and took a neat header into the snow, and after waving her a fond farewell with the toe of my right shoe, I kicked out of the valley by the Doone Gate, for I had no fear of any Doone now. Indeed, several spied my snowshoes flapping along atop of the snow, and one had a shot at them, but apart from breaking a calfskin strand or two he did no damage.

For a week I was busy building a sledge whereon to carry my Lorna away, and it was not until the eighth day (for I am but a simple fellow) when I wished to ask John Fry for a nail or two, that I thought of him and snowshoed back to where I had left him on top of the hill. As I approached I was filled with great fear, for the snowshoe that I had left kicking vigorously was now silent and still, and I climbed my tree with great forebodings of disaster, but when I shouted his name aloud he answered.

"I be doon 'ere, Jan," he said, in what seemed to me a weak voice, and I reached down and seized the snowshoe and gave it a vigorous pull. It came up with unexpected easiness, so that I almost fell off the tree, but when I looked to see John Fry I saw but his leg, and still heard him calling from below, and I laid the leg across a crotch of the tree and dived for him.

"Baint no good znowshoein' wuth one znowshoe, lad," he said, when I had recovered him. "Doon'ty try ut. I kicked and I kicked 'tull I rackon I be near 'ome but I doon't but kick old laig off."