from American Magazine

The Man With the Glass Front

by Ellis Parker Butler

The impetuosity of Tom Golding was something like record-breaking. He was a flash thinker and a quick actor -- too quick, for nature had not cut him out for that sort of man. There are men, you know, whose impetuosity is their success, but Tom wasn't that kind of man. If you looked at his long, thin, serious face when he was asleep, you would say: "There is a man who will think twice before he acts." If you saw his long limbs and big feet you would decide that they belonged to the most circumspect man in the State. In repose, Tom looked like a case of natural born laziness, but his looks were a misfit. Of all the excitable, impetuous, reckless men he was the utmost superlative.

His father had accumulated a good bit of money for a merchant in a town the size of Gilmanville, and he left it to Tom, together with the queensware store. It was a fine start for a young man, and as soon as Tom was his own master he set right in to do wonders. He would bang out of bed at five o'clock in the morning, slapping his two big feet on the carpet like slabs of wet tan bark, and make a dash at the wash-stand and a jab or two at his hair, and turn himself toward the chair where his clothes hung, without taking time to turn his feet, and the first thing he knew his long legs would be twisted around each other and he would crash down like a noble but bony pine tree. He had his furniture full of dents from falling against it, and when he bathed he had to use turpentine to take the varnish off his shins.

His eye always had the glitter of haste, and as he went down stairs he would miss about one step in every three and jar down onto the next so hard that his teeth would rattle. Sometimes he missed the top step and fell all the way down.

He would hurry at his breakfast like a man who had just one minute in which to catch a train. Old Aunt Polly, who cooked for him, once gave him a hard boiled egg and he ate it shell and all.

After breakfast he would dash for the store, swaying like a camel and swinging his arms as if he was reaching forward to grasp the air and pull himself ahead by it. People walking on the same side of the street stood aside until he got by. He usually reached his store by six and started right in, banging against the locked door, feel in all his pockets for the key and have to go back home for it. He usually got inside his store about eleven o'clock. Once in the store he had to hurry to make up for lost time, and he darted here and there like a human humming bird, and you could trace his course by the sound of the glass and china things he knocked off the counters and shelves. He broke more each day than his profits amounted to, but that would not have mattered if he hadn't began investing in things.

Gilmanville was a great place for schemes then -- and is yet -- and all the originators and promoters went to Tom for help. It made some of them mad that he accepted their plans before they had a chance to fully explain them. He would invest in six or eight failures in his reckless way, and then he would as recklessly turn down the chance to get into something really good.

He went at courtship in the same style. He happened to think, one evening, that it was time he was married, and he dashed over to Susan Barkalow's and began to propose to her before she had time to say she was glad to see him, but Sue wasn't the hasty sort.

Six times that evening he tried to propose, but each time Sue gently cut it short. Each time he ended by remarking something about how warm it was for so early in the spring. He felt like a man in the dark who sits down on a chair that isn't there. After each attempt he was jarred, but wiser. By the time Sue began yawning and looking at the clock, Tom had considerable wisdom.

Sue was a fine girl and a believer in married life, but she wasn't going to be yanked to bliss off-hand, if she could help it. She felt that marriage was a good, solid, three-act drama, but that there should be a one-act curtain raiser of courtship before the big show began. To swap similes, she was like a man buying a horse -- she wanted to look over his points and see him trot a little before she closed the bargain.

The result of her inspection was that her heart was satisfied but her mind was dubious. She saw catastrophe ahead if Tom did not calm down. His impetuosity did not please her. When she saw him dashing about town she felt that he was too much like a decapitated chicken, and she foresaw that his aimless flopping would end in disaster.

This made her hesitate, but she saw a good mind in Tom, and that his long legs and thin trunk held possibilities of dignity if he could control his impetuosity and not scoot and spurt so much.

When she had fully made up her mind she did up her hair above it in her prettiest style, and sat on the plush sofa in such a way that there was room for two on it, and when Tom had proposed she shook her head.

"Tom," she said, "I can't! I am afraid!"

"Now, Sue --" he began like a torrent, but she stopped him.

"Well, then," he asked, "why can't you?"

"Because," she said slowly, "you would make me unhappy. You are thoughtless and hasty. You do things on the spur of the moment. Some day some little thing would anger you and you would do something terrible -- or silly."

"Susan," he cried, "I swear by --"

"No," she said, again stopping him. "I know what I'm talking about. I love you and I like you. You have a good mind, but it is too hasty. It has no chance to work. You, of all men, should be slow and careful."

Amazement sobered his face, and she liked it better so.

"I am only a woman," she continued, "but I can see some things. Is your business prosperous?"

"No," he admitted. "It ain't. It's bad. Folks are trading at Green & Dawson's."

"Because they have the kind of goods people want," she said. "I suppose you buy goods the way you walk -- too hastily. You jump at things. You have invested a great deal of money in the River Park Improvement Company, haven't you?"

"Yes," he agreed, reluctantly. "I did put in quite a bit."

"Pa said so," said Sue. "He said you bit without even looking at the bait. You always do, Tom."

He knew the indictment was true. He leaned on his hands and looked gloomy. She put her hand on his arm.

"Don't be glum," she said. "You can't help it. It is only habit. Remember that you have all the time that there is in which to do things. Hold yourself back. Be slow and cautious. Act as if you were a new laid egg and were afraid of breaking yourself. Then, in time, you will be strong instead of silly, and sure instead of foolish."

For a moment he was hurt, but he saw that she meant it for the best and he took her hand. She let him.

"And if I do, Sue?" he asked.

"If you do --" she said, smiling. "If you do; if you can be slow and cautious and deliberate for a year, I will marry you."

"Then I will be slow and cautious and deliberate," he declared gladly. "But I always thought the hustler won out in this world. It will be hard to change. If I could always have you near to remind me --"

"You can't," she said.

"No," he agreed. "I'll have to do as you said -- think I am a new laid egg, or an icicle, or a pane of glass."

He began the next morning, but he forgot before he had eaten his breakfast, and it was not until he was eating his supper that he remembered. He had had an unusually spasmodic and enthusiastic day.

"Jingo!" he said. "If I had been a pane of glass, I would have been broken forty times. My bill for glazing

would have been tremendous."

would have been tremendous."

He dropped his fork and sat gazing at his plate with an amused smile that broadened as he thought.

"Why not?" he said at length. "Why not? It's a good idea."

He put on his hat and rushed down to the store. He felt rather silly, and once inside he locked the door. From the bins under the counter at the rear of the store he drew a pane of the thinnest and clearest window glass he carried in stock. He laid this on the counter, and with the glasscutter he carefully cut out a piece the size and shape of a shirt bosom. In each of the upper corners he drilled a small hole, and through these he ran a piece of picture wire. Then he went back of the tall row of shelves and removed his coat and vest. He untied his tie and took off his collar. Then he unbuttoned the bosom of his shirt -- it was a negligee -- and slipped the wire over his head.

When he went out of his store he walked with the careful tread of an aged man. He stepped slowly and softly and he did not swing his arms. When he approached a fellow pedestrian he conscientiously stood aside, and when he met Wilcox, instead of rushing up to him and shaking his hand madly, as was his usual way, he bowed slowly and carefully -- from the waist. He was transformed from an impetuous Tom into a slow and careful Thomas.

The next morning he sat so upright and moved so gingerly at breakfast that good old Aunt Polly asked him:

"Mister Tom, ain't yo' feelin' well? Has yo' got a boil -- somewheres?"

"No, Aunty," he answered. "I'm all right. I haven't a --" He caught his words. "I should say," he amended, "I have only a little pane," and he smiled in acknowledgment of his own pun.

"Yo' wants to look out fo' them leetle pains," Aunt Polly advised. "Yo' pa he died f'om one in his chest. Where is that pain?"

Tom placed his hand low down on his vest.

"Here," he said. "I can feel it right here."

"Oh-huh!" she grunted. "Dat's no chest pain. Dat's mo' like appendix-citis. You don't want to git no appendix-citis, Mister Tom. Is that a bad pain?"

"No! No! Polly," he hastened to assure her. "I'm all right. If any pain could be good, this is a good pane."

He leaned forward to reach another slice of bread and his vest touched the edge of the table. He stopped short and pressed his hand quickly to his stomach and felt it tenderly. Nothing had broken and he sighed with relief.

Aunt Polly eyed him skeptically.

"Yo' be careful!" she admonished.

"You bet I will!" he agreed heartily, and he was.

His camel gait gave place to a dignified, upright progress. He avoided Murphy, the lawyer, who had a habit of emphasizing his words by tapping people on the chest. When he sat down he sank cautiously into the chair, and when he arose he did it like a man with the rheumatism.

His face, instead of rushing into meaningless smiles, gradually assumed a look of maturity tinged with slight anxiety. He seemed always thoughtful, and so he was. He was always listening to hear the tinkle of broken glass. Long before the year of probation was up he had gained a reputation for deliberate wisdom and was spoken of as "that dignified Mr. Golding." He deserved both the reputation and the name.

To no one, however, was the change so apparent as to Sue. At first she was delighted, but at the end of six months she felt that he had won some rights. When she had suggested the change she did not mean that he should be changed from a lover into a gentlemanly but frigidly aloof automaton.

He talked better and she liked him better, and he was far more worthy of her respect and love, but being a healthy young woman, she found his courting a little too coldly formal.

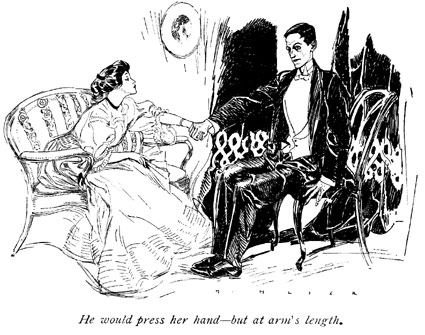

If she left room for him on the sofa, Tom sat stiffly upright on a chair. If she hinted of sleigh-rides, he did not take the hint. He was afraid to. He would take her hand -- yes, and press it -- but at arm's length.

She was provoked, and as spring neared again she permitted Will Lawfer to take her to the Y. M. C. A. lecture course. Tom suffered, but he bore his pane in silence. He did not yet dare to pour forth the love that filled his heart -- his year of probation was still incomplete.

At length the day wore around, and he awaited for evening to come with more impatience than he had imagined himself capable of. He walked to Sue's home with that stately tread she had learned to listen for. She met him rather coldly, and led the way into the parlor.

"Sue," he said, "do you know what day this is?"

"Tuesday," she answered.

"Yes, but what anniversary?"

"I am sure I do not know, Mister Golding," she said.

"A year ago, Sue," he reminded her, "you said I might hope. You said that if I could live for a year free from impetuosity you would -- would marry me."

He waited for her to speak, but she was too busy tapping the carpet with her toe.

"I have done my part," he was forced to continue. "Haven't I?"

"I suppose so," she said indifferently.

"Then," he cried, arising carefully, "you will marry me, Sue?"

"Oh!" she exclaimed, "you do want me to marry you? I didn't know. I thought -- I imagined -- You were so cold -- Lovers generally don't act like --"

Her lips trembled and she looked up at him appealingly.

He took a step forward.

There are moments when caution and deliberation are out of place. There are times when impetuosity is positively necessary. This was one of them. Tom took another step forward and reached out his arms to where she stood with downcast head.

"Dearest!" he cried, and then there was the sound of breaking glass, as if a boy had just thrown a baseball through a windowpane.