from Sunset Magazine

The Cave Men

by Ellis Parker Butler

It happened I was down there in Carter County where the subterranean wonder known as Seven Echoes Cave is located, boarding with old Jed Measure at Seven Echoes Farm when the Bishop's Pulpit in that part called the Gothic Cathedral caved over on top of Jed and ended his mortal career in one tenth of a second. That happened sometime in the afternoon and, when supper had been ready and waiting half an hour, Abundant, his daughter, came to me where I was sitting in the rocking chair on the front porch and asked me if I would go over to the cave and call Jed. I took an electric torch and went over to the cave and found Jed as dead as a door nail.

For about a month Jed had been talking about the crack that had appeared behind the Bishop's Pulpit and threatening to get cement and timber and shore up the Pulpit and cement it up solid, so I guessed that when he began to work at it the whole thing had skidded down, including about twenty tons of the ceiling and wall. A piece of pink stalactite had hit him and he was no more.

That was bad. It left his daughter Abundant a fatherless orphan and destroyed the Bishop's Pulpit, one of the showiest features of Seven Echoes Cave, but it did something else that was, perhaps, worse. It ruined Seven Echoes Cave entirely.

I discovered this even before I knew Jed was quite dead. When I saw him on the floor of the cave motionless I tried to get him to show signs of life and shouted "Jed! Jed!" at him, and no echo came back. Always, when a person stood there and even so much as whispered a word the echo would come back. If you said "Hello!" it would answer "Hello!" and "Hello!" until the last echo came back from far down the cave, a soft gentle "'lo!" And now there was no echo; not a sign of one. Those tons of rock falling had changed the acoustics entirely; they had not only killed Jed but they had killed the whole seven echoes. Abundant was not only an orphan but a pauper orphan, too.

Even while I was kneeling by poor old Jed there I made up my mind what I would do. I would stand by Abundant. I don't say it wasn't pity but I will say it was a good part love and liking. I was so sorry for the poor girl, singing away happily, maybe, in the kitchen up at the house while I was there on my knees by her dead father! My heart ached for her, and I guess nothing else would ever have given me nerve enough to think of offering to help her.

I'll say, straight out and frank, that if you took every man in every sort of show business and stood them in a row according to merit I would be at the tail end. I'm about the worst drawing card of the lot, and I know it. My line is sleight-of-hand but I'm no good at it and never was. I admit that. When I took it up I thought I was going to be a second Houdini, but in a couple of years, after I had been just about hissed off the stage of the cheapest two-a-day houses, I saw how I stacked up and I listed my name for engagements with clubs and for children's birthday parties. I got a mighty poor living out of it, and that was about all. No club ever had me back a second time, and I don't know that I blamed them much.

I was pretty well discouraged and down when I had the little accident over on Long Island and drew in my breath by mistake when I was doing my fire-eating act at a kids' party, and scorched my lungs bad. I was six weeks in the hospital and then the doctor said I needed some months in high air, with no worry and good food, or I might turn out to be a regular lunger and be done for. That was when I thought of good old Jed Measure who had been a friend of my father and knew me when I was a kid. I got up nerve enough to write to him.

Old Jed was a fine old scout. He had been in the show business in one shape or another all his life and many a time I had heard him tell father what he meant to do when he got along in years and saved up enough money to retire.

"Barras," he used to say to father, "there's just one business for a retired showman to retire to and spend his old age in ease and comfort, and that is the cave business."

It sounded reasonable, too. The cave business is a good, steady business without any worry attached. If a man owns a nice, showy cave -- not too big but well located on some main automobile route -- he only needs a few signs along the road and he is sure of a steady income. You don't have to carry fire insurance on a cave, or pay out a big payroll. A man may have to wash down the stalagmites and stalactites once in a while to keep them shining, and he has to take time to show visitors through the cave, but that is about all his trouble and expense. The rest is clear profit.

Long before he retired Jed had pretty well selected the cave he meant to buy. He has looked at a couple of hundred caves in one part of the country and another and he thought the Carter County cave field was the best. There were eighteen or twenty caves in Carter County, and that advertised the county and made folks want to go there, and one of the neatest pieces of cave property in the lot was this Seven Echoes Cave. It was the only cave Jed knew that would echo back at you seven times, each echo distinct and clear. So, when he had saved up enough money Jed bought the cave and took Abundant down there and went into the cave business, meaning to spend the rest of his life in it, as he did, poor fellow.

When Jed got my letter saying I was hard-up and sick and all he did just what you might expect any old showman to do -- he telegraphed me money to take me to Carter County and said he wanted me to stay as long as I liked. He said there was work enough round the farm -- easy work -- to pay my board and lodging, and when I got off the train, all skin and bones and bent over like an old man and holding my chest back against the cough with my hand, he made me feel like a long lost child. For a week or two I couldn't do anything but sit in the rocker on the front porch and let Abundant bring me broth or a beaten-up egg and fix the rug round my knees, but in a week or two more I was able to move round and feed the chickens and pretend I was doing work. By the time a month was up I was able to work in the garden a little and attend to the cows and fences when Jed was busy taking parties through the cave. I guess I loved Abundant from the first minute I saw her, but what right had I to think of a girl like that when nobody knew how my lungs would turn out and I hadn't a cent and she was the daughter of Jed Measure, cave owner and all? I almost wept when I thought how sweet and gentle and lovely she was and I such a busted wreck with nothing to look forward to.

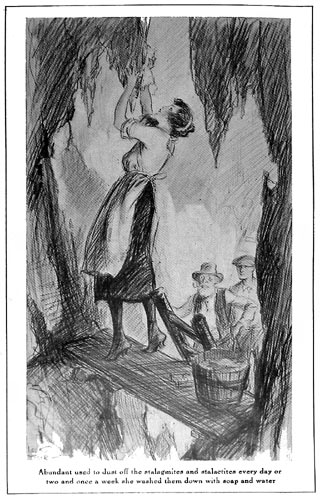

Jed was mighty proud of his cave. He had put in new steps where you go down from the Fairy Drawing-room to the Giant's Cathedral and again where you go up from the Giant's Cathedral to the Palace of the Gods, and he kept the cave as neat as a pin. Abundant used to dust off the stalagmites and stalactites every day or two and once a week she washed them down with soap and water.

"It isn't as big as Hermit Cave or Submarine Lake Cave," Jed used to say, "but I will say I've got the transparentest and prettiest stalactites in Carter County. The Hermit Cave stalactites are muddy-like. And, when all is said and done, where is there a cave with seven echoes?"

The seven echoes -- and this is the truth -- were the making of Jed's cave. He had a Bishop's Pulpit and a Pipe Organ and all the other trimmings a good cave has to have but every other cave in Carter County had the same, and it couldn't be disputed that Jed's cave was back off the main road quite a distance. People came to Jed's cave to hear the echoes and it was no use pretending anything else. With the echoes gone Jed's cave was nothing but a tenth rate cave and not worth bothering about in a county that was full of caves.

When I had worked poor old Jed out from under the stalactites and had shouldered his lifeless form I carried him to the house, but I did not have the heart to tell Abundant about the dead echoes. I just couldn't do it while she was in her first burst of sorrow. I padlocked the cave door and put a sign at the gate of the farm, "Closed because of death in family," and did what I could about the funeral and all.

After it was all over I talked with Abundant. I asked her what she thought she would do now. It was pitiful to see her trying to be brave and cheerful. She said she thought she would just let things go along as usual. Probably, she said, she would have to get an extra hand to work on the farm and a woman to be a sort of a chaperone, but she said she couldn't do anything but stay on the place and run the cave and the farm and live on the income.

How could I tell her how bad things were? The farm had never earned a cent and never would; Jed had told me that. The farm was nothing but local color. One of the first rules of the Carter County Cave-owners' Association was that every cave-owner must be a farmer or appear to be a farmer. The trade liked it. The cave-seeing trade was high class and liked to think of Carter County as plain farm country owned by plain farmers, sweet and unspoiled and unsophisticated, with nothing of the Coney Island thing about it. The minute Carter County began to be Coney Islandish the big car people would pass it by. That was plain common sense; many a cave has been ruined by the owner putting in a soft-drink stand or ice cream tables. The best cave-seeing trade likes the rustic line, with maybe the woman of the place coming out in a gingham apron and sunbonnet to offer a glass of buttermilk. Then the cave-seeing trade feels it has sort of discovered the cave. When it gets to look like a regular side-show place a cave gets passed up.

For that reason the Carter County cave owners all kept up the simple rustic stuff and had a few cows and chickens round and wore blue jeans, but there was no money in the farms. Abundant Measure's farm was one of the worst of the lot, too.

There was another thing. Jed hadn't been able to pay cash down for the full value of his farm. He had given a mortgage in part payment and had let the interest payments get behind and the man that owned the mortgage was a fellow named Rance Titherweight. He had a bad eye. I did not like him at all, and I did not like the way he looked at Abundant when he came round. He was a big, fat man, almost fifty if not fully that, and I was afraid of what he might propose now that Jed was gone and he had Abundant more or less in his fat paws, so to speak.

In our talk Abundant told me about the mortgage and all, but it did not seem to worry her. She said Jed had expected to take in enough from cave-seers that season to pay up all the interest and something on the principal, and that he would have done it before but that he had spent so much repairing the house and out-buildings.

For two or three days after the funeral I walked round that farm like a lost soul trying to think of something I could do for Abundant, and Rance Titherweight bothered me a lot. He came to the farm every day, driving up in his glossy car and telling Abundant she must not worry and holding her hand longer than necessary when he came and when he went, the fat snake! I could see she hated to have him touch her hand. After he was gone she would rush to the kitchen and scrub her hands as if he had left slime on them. It couldn't go on long as it was. I kept the key to the cave in my pocket but it stood to reason that a cave couldn't be kept closed very long on account of a death in the family, but if I opened the cave every one would know the echo was dead, and that would be the end of Abundant. Either she would have to marry that fat lizard of a Rance Titherweight or let him foreclose the mortgage and turn her adrift in the world without a cent or any experience with the world or any way to make a living.

I took my torch and unlocked the cave and went in and sat down near where poor Jed had passed away. I tried the echoes but they were only too dead. While I was sitting there wishing I was a millionaire or a second Herrmann the Great a name suddenly came into my mind. It came so unexpectedly and clearly that for a second or two I thought some one had shouted it -- "Bare-lip Bill." It seemed to settle every trouble Abundant had. I went back to the house and told Abundant I must go up to New York for a couple of days to see my lawyer or something and that I would bring back a farmhand for her, and she let me go.

I did not have as much trouble getting Bill to come to Carter County as I had feared. It was summer and nothing doing in his line or any other vaudeville line and he jumped at the chance.

"Sam," he said, "it suits me! It surely suits Bill Saggerty. You could not have come at a better time, old pal, because I've been wondering where I could go to be among the cows and the pigs and the chickens. I've got the greatest idea for a new stunt."

Enthusiastic, you understand. You know how a two-a-day man is when he thinks he has caught hold of a great idea. Sam figured that if he went to the agents with a stage set showing the dear old farm yard with its cows and chickens and dickybirds and ducks he would be dated up for about ten consecutive years in about ten minutes. He was a ventriloquist, you understand, and a good one, that being how he got the name of "Bare-lip", being able to throw his voice without moving a muscle of his face, thus doing away with his moustache. And a good one, too. I mean Bill and not his moustache.

"Sam," he said to me, "the public is dead tired of the old stunt. It is sick of the ventriloquist sitting with Little Jimbo on one knee and Little Dumbo on the other knee. My idea --"

His idea was to have a dummy dairymaid and dummy cows and chickens and ducks scattered round the stage, and he would come on with a hoe and whiskers and the cows would moo and the dairymaid talk and the chickens cackle. Then, maybe, he would slap the cow on the side and she would talk back to him, and the chickens and pigs and ducks and dairymaid would all join in -- regular ventriloquist back-talk stuff -- and the act end with the wooden pig singing a song or something.

"It will be a riot, Sam," Bill said, but no matter about that. Here was his chance to get down on a real farm and study the voice of the pig and the cow at first hand, and catch the manner of the real rustic, and be paid for it! He came back with me on the first train.

"But, mind you, Bill," I warned him, "nobody is to know you are a ventriloquist -- not Abundant or anybody. You're plain farm-hand."

When we reached the farm we found that Abundant had picked up her chaperone. She was a Mrs. Droby from the village, and a pleasant old lady enough. We all got introduced to each other and then I took Bill out to show him the farm and the cave. He loved it.

He was good, too. Once through the cave was enough to teach him every feature of interest -- "You now see on your left, ladies and gentlemen, the Giant's Jewel Box. Observe the rubies and diamonds, all true crystals, formed by Nature just where they lay. To your right --" and so on. Then we tried out

the seven echoes. "Hello!" I shouted, and Bill echoed it back to me seven times, just as good and a little bit better than the original echoes had ever echoed it. As an echoer Bill was a wonder and no mistake.

the seven echoes. "Hello!" I shouted, and Bill echoed it back to me seven times, just as good and a little bit better than the original echoes had ever echoed it. As an echoer Bill was a wonder and no mistake.

"Fine!" I said, "you'll do."

"You bet I'll do!" he said. "I've got to do. And, oh! ain't she the loveliest thing man ever saw?"

"Who?" I asked.

"That Miss Abundant," he said, and I told him there would be none of that.

"You're a farm hand and lecturer on the wonders of the cave," I said, "and you've got to know your place and keep it."

"Oh, sure!" he said. "I know that, Sam. I was just gassing. Don't get sore at a joke."

"I don't stand any jokes about Abundant," I said, and we let it go at that.

The summer moved along pleasantly enough. Bill kept the key of the cave and nobody was allowed in it without Bill in attendance, and nobody ever guessed the echo was dead, least of all Abundant. Two things worried me, however. One was that fat turtle of a Rance Titherweight, who kept pestering Abundant, and the other was the knowledge that in the fall Bill Saggerty would be going back to New York to put on his act.

About the middle of August I slipped up to New York again, claiming I had to see my doctor, and hunted round to find another ventriloquist to take Bill's place when he left, and I found an old man named Simeon Dearborn who was willing. He said he would come on the first of September, which was the day I understood Bill had set for leaving. When I reached our station in Carter County I picked up my grip and walked out to the farm. I cut across lots and went in the back way and as I neared the house I saw Abundant on the side porch, her hands clasped on her breast and her eyes raised to a tree there. My, but she was a pretty picture! But that was not what stopped me short. A little bird -- a sparrow, I guess -- was hopping round on a branch of the tree, and every time it hopped it cocked its head on one side and looked at Abundant and said "Sweetheart! Sweetheart!" which is something a sparrow don't say. I wasn't fooled. I looked round the end of the kitchen and there was Bill Saggerty with a moon-calf look on his face.

"Enough! None of that!" I whispered, and I motioned him out to the barn to talk it out and have an understanding.

"Well, what?" he asked me, defiant-like. "I can't help what the little birds say, can I? If they think she is so sweet and lovely they just have to peep up and say so, how can I help that, Sam?"

"You'll help it," I said sternly. "Abundant isn't for the likes of me or you. She's a real girl. You get your pay this evening and you leave Carter County, Bill. That's the ultimatum with the bark on it."

"Why, no, Sam," he said. "No, it ain't. Because I don't go. Because I stay right here. My act ain't ready yet and I don't care if it never is ready. I may settle down here for good and all, with a farm and a cave and a wife -- a wife, Sam -- amongst the cows and the chickens and the little dickybirds that say what they mighty well please without any blue-gilled back-number sleight-of-hand man butting in. You get the idea?"

"So that's how it is, is it?" I asked, getting red in the face.

"Just like that," a chicken answered, sneering-like, from where it was pecking seed on the barn floor. "Just like that, ain't it, Bill?"

"Seems so, chicken," Bill answered.

"Oh, well, if you've got all the livestock talking for you!" I said scornfully, and I turned away. "Only," I said, "I've hired a man to take your place down here, and you'll kindly hand me the cave key and go up and pack your trunk."

"Give him the key; what do you care?" grunted a pig, and Bill tossed me the key. I caught it on the fly and went on up to the house. Abundant was still there, looking at the little bird, and when she saw me she started and blushed.

"Why, Sam!" she said. "I didn't expect you!"

"I walked," I said.

Bill did not go. When I thought it over I saw he was right in one way, he had never said he meant to go before the first of September and I had no right to send him away; that was Abundant's business. Old Simeon showed up on the first of September and I gave him the key to the cave and explained the points of interest and tried him out on the echo. He did well enough. He was an old-styler and had a moustache to hide his lips but he echoed as well as need be and I was glad to see that professional jealousy made him sort of offish to Bill. They didn't mix.

"I thought Mr. Saggerty was going," Simeon said to me.

"Well, he said he was," I answered.

"Then he had better go," Simeon said dryly. "If he don't he will give this whole business away. Miss Abundant is liable to come on him any time. Just now he is out there making the ducks and the geese tell each other what they think of you and of Rance Titherweight, and what a lovely person Miss Abundant is."

"Drat him!" I said. "He's in love; that's what is the matter with him."

You can imagine I was surprised when Bill came to me, not half an hour later and held out his hand.

"Good-by, Sam," he said. "I'm going. It is all off. I'm on my way. I asked her to marry me. Well, such is life!"

"No!" I exclaimed. "You don't mean you had nerve enough to ask her to tie up to a thing like you!"

"She thought the way you do, I guess," Bill said with a sick grin. "She was sorry and all that, but it couldn't be. It's Rance Titherweight, Bill -- no doubt of that."

"No!" I exclaimed again. "Not that fat slug! Did she say so right out?"

"More or less," Bill admitted. "I put it up to her and she would not deny it.

"Well, you just wait here," I said, "and don't you move until I come back. I'll settle this Rance Titherweight business. I know a thing or two about Rance Titherweight -- "

I was off in a rush and I found Abundant without any trouble. I asked her if she could spare a couple of minutes and we went out on the side porch and I made her take a seat. I hesitated awhile, trying to get things straight in my mind, so I could say them in the proper way.

"It's like this, Miss Abundant," I said finally, "I've been cheating you. I've been fooling you and playing a trick on you. I'm ashamed of it and I confess it but I did think I was doing the right thing, and that is my excuse."

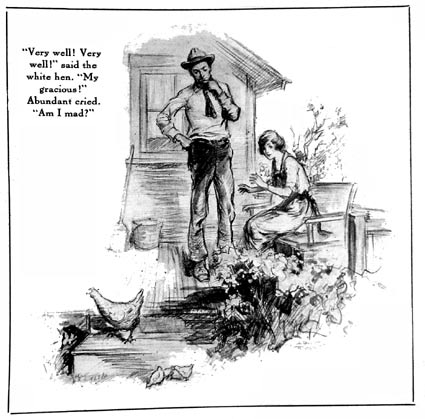

Just then a chicken came along, pecking at the grass out in front of us. It was a white chicken, a hen, and along behind it came half a dozen chicks, a late season hatching of them. The hen started to come up on the porch.

"Shoo!" said Abundant.

"Very well! Very well!" said the white hen. "Don't get excited."

"My gracious!" Abundant cried. "Am I mad?" and she looked up at the tree where the little bird had said "Sweetheart!" the day I came back from New York.

"Don't worry," I said, sarcastically. "That's Bill. I'm going to tell you everything: And, first of all, I want to tell you that Bill is not half as bad as you may think he is."

"I don't," said Abundant. "I don't think he is bad at all."

"All right, then," I said. "First I want to confess that when that Bishop's Pulpit fell and killed your father it spoiled the seven echoes in your cave. It killed all seven of them; not an echo was left. And you know what that meant to the cave. It ruined it."

She simply stared at me.

"Yes," I said, "I know what you are thinking. The cave has kept right on echoing. That's right enough, but I'm to blame for that. I was a coward and held back the truth from you, and I went up to New York and hired Bill for you, and Bill is a ventriloquist."

"He is a --?" she asked.

"Ventriloquist," I said. "A voice thrower. And old Simeon is another. I thought I could keep the dead echoes from your knowledge and let Bill take the tourists through and do the echoes for them."

"But why?" she asked.

"On account of Rance Titherweight," I said, "and on account of you being alone in the world and unable to support yourself and all. I don't expect you to forgive me, but that don't matter. I thought I was doing right."

"But why should you do it for me?" she asked.

"Because," I said, right out flat, "this cave without the echo is not worth the powder to blow it up, and Rance Titherweight was making eyes at you. Suppose you married him -- he would find out the cave was worthless and he would treat you mean."

"Treat me mean?" she asked. "Don't you think he cares for me for myself, then, at all?"

I did not answer that; I did not like to. But the white hen did.

"Not a bit, the fat serpent!" the white hen seemed to say. "He don't care a darn for you."

"Excuse me a minute," I said to Abundant, "I'm going to find Bill and knock his head off. I won't have him butting in on this conversation."

Abundant put out her hand.

"No, don't!" she said. "What does it matter?"

"Very well," I said. "I'll go on with my story. I thought, if Rance married you you would be unhappy, and to marry him seemed the only thing you could do. If you did not he would foreclose the mortgage and throw you out, and then he would discover the echo was dead and he would make all kinds of trouble for you. So I had Bill come down and it all worked well. And it will continue to work well. Simeon is not as good as Bill at voice-throwing, but he makes a good enough echo. So why don't you just let things go on as they are?"

"Am I not going to?" she asked.

"Well, no!" I said. "I don't think you are, and that's the trouble. You're going to marry Rance."

"Who said that?"

"Bill did. He practically said you said so."

She did not deny it. She looked at the white hen and at the late-hatch chickens and said nothing.

"All right then," I said, taking a new grip on my courage, "I ask you not to marry that Rance fellow. He's a crook and a slimy character and you'll be unhappy every day of your life. Take Bill instead. I know Bill and I know he is better than most fellows. Give him a chance. Don't turn him down the first shake out of the box. Let him have a chance to show you what a real man he is."

Abundant looked out across the grass patch. She let her hands rest in her lap. It almost broke my heart, she was so sweet and pretty and innocent. I could hardly bear to look at her pretty mouth with her lips just parted like two rose petals. And then that fool hen had to speak up again.

"Bill has no chance," the hen said. "She don't care for Bill at all. If I were a man --"

"Drat you!" I cried, and I raised up and felt for something to throw. I had nothing but my hat, and I threw that. The hen squawked and scuttered away. "I'll go round and paste Bill one in the jaw in a minute," I said.

Up in the tree a sparrow fluttered from one twig to another.

"Sweetheart! Sweetheart!" it chirped in real words.

I looked out and down the road, too far to throw his voice to us, was Bill -- going to the station to buy a ticket, I suppose. Over in the cave lot, almost as far away, was old Simeon. I looked at Abundant again, and she was just as before, looking out across the lot, with her lips just parted. Then the old white hen came back a step or two and looked up at me doubtfully, not knowing whether I would throw another hat or not.

"Excuse me," said the white hen as meek as Moses, "I just came back to say that if I were a man and cared anything for a lady I would speak for myself."

I swear I was trembling all over! I turned to Abundant and put out my hand. "Could you?" I stammered. "Could you love me, Abundant?"

She gave a sort of sob and put both her hands in mine.

"Oh, Sam! you are such a fool!" she said, and then we laughed and everything was all right forever.

"And how was I to know you had the voice-throwing trick yourself?" I asked her some time later, when things had loosened up so that I had only one arm round her.

"As if father would figure to leave me a cave as a legacy without preparing me to keep the echo going!" she cried.

That's all. Jed had been a voice-thrower himself. There never had been any real echo in Seven Echoes Cave. It is simple enough when you know the trick; Abundant taught me in less than a week. Since she has the children to look after I show the visitors through the cave myself. We are prospering nicely and, next year when I get the last of the mortgage paid off, I'm thinking of putting in an extra echo. I won't change the name of the cave but I believe in giving full measure and running over, my own blessings, so to speak, having been Abundant.