| ||

| ||

from Pictorial Review

Mr. Middlemay's Alibi

by Ellis Parker Butler"Very well, then," said the police magistrate sternly, "I will hold this case over until tomorrow, and if this man can prove an alibi he had better do it and do it well, for it looks decidedly serious for him."

"Thank you, your honor," said Mr. Hillier. "Now, as to the matter of bail --"

"No bail!" said the magistrate shortly.

"But if your honor pleases!" said Mr. Hillier politely. "I am sure your honor does not wish an honest man to be condemned merely because he cannot get his witnesses into court. My client has abundant witnesses to prove an alibi. He can prove he was nowhere near the spot where this crime was committed yesterday afternoon. He can bring witnesses that he is a man of good character, and he can bring witnesses to prove a complete alibi, but he is in the unfortunate position of not knowing the name of a single one of his alibi witnesses. If you lock him up until tomorrow he will be almost surely convicted and I assure your honor that would be a most serious miscarriage of justice. I ask most respectfully but most seriously that you permit my client to give bail."

The magistrate looked at the young lawyer as if seeking to fathom that young man's inner thoughts.

"I do not seem to remember your face," he said. "I presume you are a member of the bar of this county?"

"Yes, your honor," said Mr. Hillier. "If you will permit me to be somewhat facetious, I will say I am one of the last job lot of lawyers admitted. As a matter of fact, I am making corporation law my work, and I would not attempt to defend a case of this sort if it were not such a simple case. If you wish to learn more of my character I can refer you to Judge Wilmerton and to Judge Hover."

"They know you pretty well?" asked the magistrate, folding his hands.

"Yes, your honor. Judge Wilmerton is my uncle and Judge Hover is my mother's cousin. I assure you, your honor, that there is no reason why my client should not be released under bail. I am a neighbor of his. I live next door to him, and I have come to town with him, from Westcote, nearly every business morning for several years. I can personally vouch for the fact that he is a respectable suburbanite, with a wife and family. He is employed by a man I know very well."

"That is rather different than I had supposed," said the magistrate. "How did he get into this trouble?"

"If your honor pleases," said Mr. Hillier, "he did not get into it. My client has nothing to do with any trouble. It is simply and purely a case of mistaken identity. He was arrested through some likeness he must bear to the man really guilty. If you will allow us to subpoena the witnesses we need, and will permit Mr. Middlemay to go personally to identify the witnesses, we can prove an alibi for every minute of the day, from two until five in the afternoon."

The magistrate looked at Mr. Hillier with less sternness. He rather liked the young man's face.

"I will parole the prisoner in your custody, Mr. Hillier, until this case is called tomorrow. Can you be ready at eleven tomorrow morning?"

"Can we?" Mr. Hillier asked Mr. Middlemay.

"I -- I guess so," said Mr. Middlemay, in a hoarse whisper.

"My client thinks he can," said Mr. Hillier. "Thank you, your honor. Come along, Middlemay."

Together they left the courtroom. The young lawyer's bright, clean-cut face showed no worriment, but Mr. Middlemay's face would have done as a model for a sculptor wishing to make a statue of "Anger Enveloped in the Garments of Despair." Mr. Middlemay had spent the night in jail and he did not like jails. It was the first time he had ever seen the inside of one, and while he might in time have come to like jails if given a chance, he hated it. A jail, however hygienic and modern, does not at first seem pleasant to a man accustomed to sleeping in a clean bed in a room with Oriental rugs scattered profusely about the floor and pale pink striped paper on the walls.

"If I ever get out of this," said Mr. Middlemay angrily, as Mr. Hillier led the way out of the police court, "I'll tell Sally what I think about it. I told her yesterday morning, but she said I could do it as well as --"

"Do you want to telephone her?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"Telephone her?" asked Mr. Middlemay crossly. "What do I want to telephone her for? I telephoned her last night, didn't I? That was one lie -- telling her I had to stay in town on business. What do I want to telephone her for again? More lies?"

"I think she'll have to know," said Mr. Hillier. "It is really no disgrace to be locked up overnight on a false charge, Middlemay. Now, in proving your alibi she should be your first witness. You can see that."

Mr. Middlemay groaned.

"And I'll never hear the end of it," he said. "She said yesterday morning, when I was telling her in words of one syllable what I thought of any woman that would give a man a job like that, that I made as much fuss about it as if she had asked me to break into a penitentiary and rescue a life prisoner. 'You make as much fuss,' she said, 'as if I was asking you to commit a crime and be jailed for it. And all I want is --'"

"I'd tell her," said Mr. Hillier. "Some one will hear of it and tell her, anyway, and it will seem much worse if it comes to her that way. We'll stop at the first pay station and telephone her, and that will be all right. I want her in court tomorrow at eleven."

"Well, there's no need of telling her what I'm supposed to be in jail for, is there?" asked Mr. Middlemay, reluctantly. "I don't want her to have convulsions. If she heard wrong over the telephone, and got an idea that I had --"

"I will telephone her," said Mr. Hillier, and he did. After he had explained Mr. Middlemay's predicament, and had told Mrs. Middlemay that her husband might be so busy he would be unable to get home that night, he hung up the receiver and turned to Mr. Middlemay.

"Well, what did she say?" asked Mr. Middlemay, anxiously.

"Do you want to know?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"Of course I want to know," replied Mr. Middlemay.

"Her remark," said Mr. Hillier, "was somewhat cryptic. Perhaps you can understand it. She said 'That is what I might have expected of a man who brought home a ball of carpet yarn when I sent him for number sixty white, silk finish crochet cotton.'"

"Great Caesar!" exclaimed Mr. Middlemay. "I left that cap somewhere, after all!"

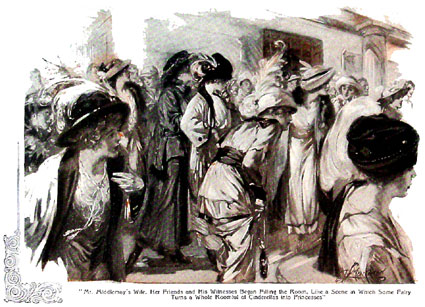

At eleven o'clock the next morning police magistrate Fetter's court-room was more crowded than usual, although by that hour most of the cases for the day were apt to have been disposed of and the room well cleared. The room began filling about half-past ten when Mrs. Middlemay entered. She was a tall, rather severe woman of the sort capable of taking care of themselves, but as this was her first experience in a police court, or any other court, she had brought a few friends from Westcote to support her in case the ordeal should be too great. While not dressed in the exact manner required for attendance at an afternoon social function, Mrs. Middlemay and her friends were considerably more plumed and silked than Magistrate Fetter's courtroom's usual habitues favored. In fact, a few hours earlier the room seemed to have held most of the forlorn rags and tatters of the great city, and the change as these disappeared and Mr. Middlemay's wife, her friends and his witnesses began filling the room, was like a scene in which some fairy turns a whole roomful of Cinderellas into princesses.

With Mrs. Middlemay were Mrs. Billinghurst, Mrs. Freeman, Mrs. Rotch, Miss Perkins, Mrs. Schultz and Miss Dougherty. Mrs. Middlemay quite properly wore a dark veil and carried a white handkerchief against the necessity of dabbing at her eyes, should the necessity arise. They quite filled one of the spectators' benches, and Judge Fetter adjusted his black gown's folds with care as they took their seats, although but little of his gown could be seen by the ladies.

"Good-looking lot of ladies," he said to his clerk. "Probably slumming the courts. Wish they could have been here to hear that assault and battery case."

He felt he had handled the assault and battery case rather well, and it was the sort of case court slummers liked to go home and tell about. It had a moral that stuck up like a sore thumb.

"Have we got anything interesting?" he asked the clerk, but even as he asked he stopped and stared at the doorway.

"What's all this?" he asked. "Did you hear anything about a musical comedy going to rehearse here, Flannery? Or is there a female convention on today?"

Mr. Flannery looked toward the door. He ran his hand over his perfectly bald head, as if to smooth the hair that was not there. Girls were coming in at the door now -- young girls and some middle-aged girls -- and as they crowded in they looked like a horde of girls. In reality there were not many, only ten or twelve, or possibly twenty. With them were several stately and well-dressed men, severely upright in carriage and serious of face.

"I tell you what it is," said Flannery knowingly, "I think it's one of them excursions where they bring the school to town to see the wheels go round. Them men look like professors to me."

"Have Mike ask one of the men," said the magistrate, and when Flannery had asked Mike and Mike had asked the most serious looking of the men, Mike told Mr, Flannery and Mr. Flannery told Judge Fetter.

"Those are that Mr. Middlemay's witnesses," said Mr. Flannery.

"Great Caesar!" said Judge Fetter. "The man must have spent his afternoon at a tango tea. Call the next case, Flannery."

The next case was Mr. Middlemay's case, and as the clerk called his name, summoning him to appear at the bar of justice, Mr. Middlemay, properly in the custody of Mr. Hillier, entered the courtroom. He stopped to speak to his wife, shook hands with all the ladies from Westcote, and entered the prisoners' box.

"Now, then," said the magistrate. "Who is the first witness in this case? You, Officer Maloney?"

"I do!" said Officer Maloney, when asked if he proposed to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, and lowering his hand he seated himself in the witness box. He laid his hands on his knees and smiled at the courtroom in general.

"Now, Maloney," said the magistrate, "tell us what you know about this case."

Officer Maloney told. He was evidently pleased with himself because of his good fortune in arresting Mr. Middlemay, and he dwelt on the details. The magistrate had to cut him short several times, but there was no doubt that he had arrested Mr. Middlemay when that person was running down the street at a rapid gait.

Mr. Carney followed Officer Maloney. He told of the crime and of following the criminal until he entered a department store. He was sure he could identify Mr. Middlemay as the criminal. He'd swear to it, anyway. Yes, the crime was committed at two-thirty o'clock. Just about two-thirty, maybe a few minutes earlier or a few minutes later. Then, what? Why, then he saw the prisoner hide in the shed. It was dark in the shed but he could see the prisoner's legs all the time. He didn't dare go for a policeman because he was afraid the prisoner would get away while he was gone. He waited and about three-thirty o'clock the prisoner walked out of the shed with his back toward him, and he, Carney, followed him at a distance. He didn't see a policeman until after the prisoner had entered the department store. He saw a policeman just as the prisoner entered the store, and he didn't know whether to follow the prisoner or stop and speak to the policeman, but he stopped and told the policeman.

The policeman immediately spoke to three plain-clothes men who were on the corner, and they heard the description of the prisoner and stationed themselves at the doors of the department store and waited. Carney was with the officer in uniform. Yes, with Officer Maloney. At five o'clock the prisoner dashed out of the department store and started to run toward the Avenue, but Officer Maloney caught him.

"Are you sure this is the man?" asked the magistrate.

Carney had arisen from the witness box. He sank into it again.

"Yes, sir," he said. "I'm as sure of that as I can be of anything. I took good notice of his clothes and his build and all that."

"Do you think there were other witnesses to the crime?" asked the magistrate.

"Oh, sure!" said Carney. "Taking place that way in the court of an apartment house? There must have been."

The magistrate told Carney that was all, and Carney left the box.

"Well, Mr. Hillier," he said, "have you prepared your alibi?"

"I have, your honor," said Mr. Hillier, "but I ask you not to take up your valuable time with this case. I call the testimony flimsy."

"It is enough to hold the prisoner for the action of the Grand Jury," said the magistrate. "If the Grand Jury thinks it is too flimsy to warrant a trial, the case will be dismissed. You seem to have enough witnesses."

Mr. Hillier smiled.

"I had to have them all," he said. "Shall I proceed?"

"Do so," said the magistrate.

"Mr. Middlemay!" said Mr. Hillier, and Mr. Middlemay, accompanied by a big policeman, left the prisoners' box and entered the witness box. He was duly sworn and seated himself.

"Now, Mr. Middlemay," said his lawyer, "you have heard the witnesses who have just testified here, have you not?"

"Yes, sir," said Mr. Middlemay.

"Were you in the court behind the Rosarol Apartments from two-thirty until three-thirty day before yesterday afternoon -- that is Tuesday afternoon?"

"No, sir," said Mr. Middlemay.

"Were you ever in the court behind the Rosarol Apartments?"

"No, sir."

"Do you know where the Rosarol Apartments are?"

"No, sir."

"You are a business man? Doing business in New York city, on Twenty-sixth Street?"

"Yes, sir. I work there. I'm bookkeeper for Hornby & Blatz, lace skirts."

"And you live at 443 Elm Street, Westcote, Long Island?"

"Yes, sir."

"Married man?"

"Yes, sir."

"Is your wife in the courtroom?"

"Yes, sir. She's the third lady from the end on the first seat on this side of the room."

"And do you see any of your neighbors here?"

"Yes, sir. The ladies with my wife are all neighbors."

"If necessary, your honor," said Mr. Hillier, "I will later call on the ladies to testify to Mr. Middlemay's good character. Mr. Middlemay, do you see Mr. Hornby, for whom you work, in the courtroom?"

"Yes, sir, I do. He's the thin gentleman, third seat from the back, on the other side of the room."

"If necessary, your honor, Mr. Hornby will testify to Mr. Middlemay's character later on. Now, Mr. Middlemay, I want you to tell me -- and his honor -- just what you did day before yesterday, where you went, and all about it. Go on, Mr. Middlemay."

"Well, your honor," said Mr. Middlemay, turning toward Judge Fetter, "you see, I have a pair of twins at home -- twin girls -- and they are four years old --"

He glanced toward his wife and she nodded her head. "That's right -- four years old," said Mr. Middlemay, "and last week my wife came to town and bought them a couple of coats and hats and I thought they were fixed for the Winter. But you never can tell, Judge. So Tuesday morning my wife said to me, 'Augustus' -- my name is Augustus -- 'Augustus, I wish you would stop at the department store and get the twins a couple of tam-o'-shanter caps." I said 'Martha' -- her name is Martha -- 'Martha, there are a lot of department stores in New York, which shall I stop at?' 'Any one,' she said, 'they'll all have children's tam-o'-shanters. And be sure to get white ones -- white woolly ones.' 'I understand,' I said, 'sort of angora. The fuzzy kind.' 'Yes,' she said. So I came to town, just as I always do, and I went to the office and worked all morning. Mr. Hornby knows I did."

"Very well," said the magistrate. "Proceed, Mr. Middlemay."

"Then I went to lunch," said Mr. Middlemay. "I went at twelve o'clock, and I ate at the Dairy Lunch. I had corned beef hash and a --"

"Never mind what you had," said the magistrate. "Proceed."

"Yes, your honor," said Mr. Middlemay. "And I left at half-past twelve. I can prove that, because I looked at my watch, and the waitress is in court. Her name --" said Mr. Middlemay, "is Miss Rosa Mitchell."

"Will Miss Mitchell please stand up?" said Mr. Hillier, and a rosy-cheeked girl near the center of the courtroom arose.

"Is that the girl?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"Yes, sir," said Mr. Middlemay. "So I looked at my watch and I saw I had half an hour before one o'clock so I thought I would drop into the department store and buy the tams. So I walked down the street --"

"Did you meet any one you knew?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"Yes, sir, I met Mr. Dobley of our office halfway between the lunch room and the department store," said Mr. Middlemay. "He is in the back of the room."

"Will you please stand up, Mr. Dobley?" asked Mr. Hillier, and Mr. Dobley, a thin young man, arose. "Thank you," said Mr. Hillier. "Go on, Mr. Middlemay."

"So I went into the department store -- the Golden Eagle, it was -- and I walked about twelve feet down the aisle," said Mr. Middlemay, and I met a floorwalker. So I asked him where the children's tam-o'-shanters were and --"

"One moment," said Mr. Hillier. "Do you see the gentleman in court?"

"Yes, sir," said Mr. Middlemay, "he is the tall man with spectacles, behind my wife."

"Proceed."

"I asked him where the tam-o'-shanters were," said Mr. Middlemay, "and he said 'Millinery Department -- third floor -- take the elevator.' So I rook it."

"And do you see the elevator man in court?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"Yes, sir," said Mr. Middlemay. "He's the man in uniform over in that corner."

"Very well," said Mr. Hillier. "Continue."

"So I went up to the Millinery Department on the third floor," said Mr. Middlemay, "and I asked the floorwalker --"

"Is he in court?"

"Yes, he's the man sitting --"

"Very well, go on."

"I asked him where children's tam-o'-shanters were," said Mr. Middlemay, "and he said 'Second aisle over, middle of the store,' and I went there. There were two young ladies there, talking about a dance they had been to, and I waited --"

"Do you see the two young ladies in court?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"Yes, sir, they are right there," said Mr. Middlemay, pointing. "They are --"

"No matter. Proceed, please."

"So I waited, and when they were through talking," said Mr. Middlemay, "I asked them to show me children's tam-o'-shanters."

"Very well," said Mr. Hillier. "And what next?"

"They asked me how old the child was," said Mr. Middlemay, "and when I said four years they said they did not have any. They said the four-year-old tam-o'-shanters were in the Infants' Wear Department, fifth floor; take the elevators on the other side of the building. So I took the elevator on the other side of the building --"

"Do you see that elevator man in court?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"Yes, sir," said Mr. Middlemay. "There he is. So when I got to the fifth floor I asked the floorwalker --"

"You see him in court?"

"Yes, sir. And he pointed to the Infants' Wear Department, and I went there and spoke to the young lady in charge --"

"And you see her in court?"

"Yes, sir, and I asked her to let me see four-year-old children's tam-o'-shanters, and she said 'We only have up to three years old here. You'll find them in the Girls' Wear Department, fourth floor. Take the elevator in the rear of the --'"

"And you see that elevator man in court?"

"Yes, sir. And when I got to the fourth floor, I asked the floorwalker --"

"And you see him in court?"

"Yes, sir. And he sent me to the Girls' Wear Department, and I spoke to a middle-aged lady and --"

"You see her in court?"

"That's her, there," said Mr. Middlemay, wiping his face nervously. "And I asked her for four-year-old caps, and she showed me hats. She showed me stocking caps, too. She showed me dozens of them, Judge, but no tam-o'-shanters. So I said 'These are nice, but I wanted tam-o'-shanters.' So she threw down the cap she had in her hand and she said, 'Why didn't you say so? All the tam-o'-shanters are in the Sporting Goods Department, on the sixth floor.' So I --"

"And you see that elevator man in court?"

"Yes, sir. And I --"

"And you see that floorwalker in court?"

"Yes, sir. So I spoke to --"

"And you see that saleslady in court?"

"She wasn't a saleslady," said Mr. Middlemay. "He was a salesman. He was selling a hockey stick to a boy --"

"And is that boy in court?"

"No," said Mr. Middlemay sadly. "I don't know where he is. Maybe he is playing hockey somewhere. If I had time --"

"No matter," said Mr. Hillier. "And then what happened? Is the salesman in court?"

"Yes, sir," said Mr. Middlemay. "So I asked him if he had children's tam-o'-shanters, and he said he had. He said 'Three aisles to the left, and keep straight ahead.' So I did. And the young lady --"

"She is in court? Yes? Proceed, Mr. Middlemay."

"She had a lot of tam-o'-shanters," said Mr. Middle-may, "but --"

"But what?" asked the judge.

"They were all women's sizes. They used to have children's sizes, your honor, but the cold weather had made a run on them and they were all sold out. But she said I wouldn't have any trouble in finding them," said Mr. Middlemay. "She said she had seen a table full of four-year-old sizes in the Millinery Department that very morning. She told me they were in the exact middle of the department so I went down and I asked --"

"Is that young lady in court?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"I asked three," said Mr. Middlemay. "They're all in court. And they all said they had never had children's tam-o'-shanters in that department. They said it must be the middle of the ground floor, because that was where special bargains were, so I went down."

"And those three young ladies are in court? And the elevator man is in court? And --"

"Yes," said Mr. Middlemay, "and the three other floorwalkers I asked are here. But there were no tam-o'-shanters there. There were silver-plated hair-brushes."

"Then what did you do?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"I went out of the side door," said Mr. Middlemay. "I see the doorman in court. And I went across to the Green Star Store and --"

"Do you see any one in court from the Green Star Store?" asked Mr. Hillier, and as he spoke, the door opened and eighteen or twenty young ladies and five men of various ages entered.

"They are just coming in," said Mr. Middlemay. "They are the floorwalkers and the salespeople from the Infants' Wear Department and the Millinery Department and the Girls' Wear Department and the Sporting Goods Department. And they all thought some other department had four-year-old tam-o'-shanters, but they did not. No, sir! So I went across the street to the Universal."

"And --" said Mr. Hillier.

"I don't see any one from there here," said Mr. Middlemay.

They will be here in a minute or two, your honor," said Mr. Hillier to the magistrate. "Go on, Mr. Middlemay."

"I went to all the departments in that store," said Mr. Middlemay, "that they told me to go to. I went to the Infants' Wear and the Girls' Wear and the Millinery and the Sporting Goods, and nobody had four-year-old tam-o'-shanters, at all. They seemed to know what they were, and had dim recollections of them. You could see their faces brighten when I mentioned them, your honor, and they were all very pleasant and helpful and sent me directly to where the tam-o'-shanters were, only they were not there when I got there. So --"

Mr. Middlemay was interrupted by the entrance of another bevy of young ladies and men.

"You now see the persons who saw you in the Universal, do you not?" asked Mr. Hillier.

"I do," said Mr. Middlemay.

"One moment!" said the magistrate. "You began shopping at half-past twelve? And when did you leave the Universal?"

"Just in time to catch my train for Westcote, your honor," said Mr. Middlemay. "I had to run for it, and while I was running I was grabbed from behind --"

"I see!" said the magistrate, and he turned to Mr. Hillier. "I think you may let all these people you have brought here as witnesses go," he said. "They are doubtless needed at the business places where they work, to direct helpless individuals where to find tam-o'-shanters."

"We are quite willing to put them on the witness stand, your honor," said Mr. Hillier.

"I don't think that will be necessary," said the magistrate. "In fact," he continued, "none of them is necessary to prove an alibi for your client. In proving an alibi of this sort just two witnesses are needed -- the lady who asked the gentleman to step into a department store to make a purchase, and -- the article purchased. The mere fact that the man who was asked to make the purchase did make it accounts for at least a full afternoon spent innocently. You may all go," he said to the waiting department store people, "or -- wait! Kindly pay attention to the answer to the question I am about to ask." He turned to Mr. Middlemay. "Where," he asked sternly, "did you at length find the white angora tam-o'-shanters for the four-year-old girl twins?"

"In the Boys' Hat Department," said Mr. Middlemay.

"Have you a witness to that effect?" asked the magistrate.

"No, sir," said Mr. Middlemay. "The young lady I bought the tam from was sick this morning."

"I think no witness is necessary," said the magistrate judicially. "Common sense should make it clear that if you found four-year-old girls' tam-o'-shanters anywhere in a department store it would be in the Boys' Hat Department. I consider your alibi complete. You are discharged."

"Thank you," said Mr. Middlemay, and he arose and started from the witness box.

"One minute!" said the magistrate. "I suppose you have the tam-o'-shanters to place in evidence?"

"I -- I --" stammered Mr. Middlemay. "I don't know."

"What's that?" asked the magistrate sternly. "What do you say?"

"I say I don't know," said Mr. Middlemay nervously. "The police took the package away from me."

"But you had the two white angora four-year-old girls' tam-o'-shanters, didn't you?" asked the magistrate.

"No, sir!" said Mr. Middlemay. "I only had one. They only had one in the Boys' Hat Department. I told the girl one wouldn't do, but she said --"

"What did she say?"

"She said I could get another in the basement. She said she had seen some in the basement that morning. So I took the one she had, and I thought I'd go back the next day and get --"

"Augustus Middlemay!" exclaimed Mrs. Middlemay, arising from her seat. "Augustus, do you mean to say you spent a full half day, and were arrested, and brought into court, and made me come all the way from Westcote, and made all this trouble, and then got a tam for only one of the twins? Do you mean to say that?"

Ye -- yes, Sally! said Mr. Middlemay.

"What did you pay for it? Not over fifty cents, I hope!"

"Ninety-eight," said Mr. Middlemay faintly.

"Well!" said Mrs. Middlemay. "Well! And you are one of the men who think the women do not know enough to vote! One tam for two girls! Augustus, as soon as you get out of here you take that tam back and exchange it for three yards of white silesia and a card of black hooks and eyes! Understand?"

Mr. Middlemay whispered hurriedly to Mr. Hillier, and Mr. Hillier spoke to the magistrate.

"If it please your honor," said Mr. Hillier, "my client would like to withdraw his alibi. He will plead guilty to the charge originally brought against him, and ask for the lightest sentence your honor can impose. Justice should be tempered by Mercy, your honor, and I beg to call your attention to the fact that my client has spent one-half day in department stores trying to buy goods and a full day looking up these witnesses. He has had a day and a half of it, your honor, and if you set him at liberty he will be obliged to undergo the most frightful torture a man can experience, exchanging goods for others. My client is unfit to be trusted with shopping errands."

For a few minutes the magistrate sat in thought, looking at Mr. Middlemay and tapping his fingers together.

"Denied!" he said at last. "In my opinion your client is not unfit for shopping errands. I have shopped in department stores myself. I rule that your client had less difficulty than is usual, that his alibi was proved and that it is at least his duty to see whether there are tam-o'-shanters in the basement of the Universal. And," he added, to Mr. Middlemay, "if you find any there, let me know. For a week, three of the city detectives have been busy trying to find a white angora, four-year-old tam-o'-shanter for my little daughter. Court stands adjourned."

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 7:18:01am USA Central