| ||

| ||

from Seng Book

Playing the Game

by Ellis Parker ButlerEveryone has read -- or heard of -- "Pigs Is Pigs," a humorous story of years ago that went through many large editions. The book made its author, Ellis Parker Butler, instantly famous, and he maintains his prestige through the frequent appearance of articles and stories in big magazines, like "Cosmopolitan." Mr. Butler writes of serious, helpful things in a light and readable way, and in the article which follows tells you how to live, something, indeed, that's always worth reading. -- The Editor.

I am now fifty-six years old, getting gray and bald, and young ladies on the street no longer turn and stare after me because of my youth and beauty, but I am still alive. It gives me pleasure to announce this because, as far as I have been able to figure out up to this time, being alive is one of the best things a man can be. It is all well enough, I dare say, to be a sweet memory and part of the underpinning of a tombstone and the gentleman the widow speaks of with regret up to the time she marries the new one, but as long as food has such a good taste and a man can have plenty of smoking tobacco I prefer to be alive.

I may be prejudiced about this, but the way it looks to me is that there is no need to be in a great hurry to be dead. It is nothing to get in a rush about, like catching the Twentieth Century Express or getting to the bathroom before Mary, because there is going to be plenty of time in which to be dead, no matter what happens. The period following my decease is not going to need any time table; it is going to be from then on and, judging by the time some fellows have been dead -- King Tut, for example -- the "on" is going to be quite some length of time. Even if a man manages to stretch out his life as long as Adam's and live nine hundred and thirty years he need not worry -- he'll be dead long enough anyway. Adam may have fretted because he was afraid he was living up all the time there was, but he need not have worried -- he has now been dead just exactly five thousand years and it looks as if he would be dead quite a while longer.

I have now loafed along through life quite comfortably until I have reached the point where too many of my friends and acquaintances are where Adam is and where King Tut was until they took a crowbar and pried him loose. I am still a young man -- at least if you reckon by Adam's nine hundred and thirty years, or Methuseleh's nine hundred and sixty-nine -- but too many of my set have quit on me and gone below ground. I don't like it. The trouble is not enough playing is being done. The missing are almost entirely those who did not play or who did not know how to play in the right way. If a man is going to live and be happy -- and the unhappy ones cave in earliest -- he must work, sleep and play.

There is no need to say anything about work; everybody works these days, including father. I'll bet a box of cigars that there never was a time or place in the world where people are so crazy to work as right here in America today. We all work and, although some of us hate to admit it, we all like to work. Some of us couldn't be driven from our work by anything less than an earthquake.

And some of us sleep. If you ever went through a bed factory you would think nobody ever did anything but sleep, excepting only the bed manufacturers and that they were all working overtime. I'll bet another box of cigars -- but not such good ones -- that if the steel rails for wood beds were placed end to end they would reach from Insomniaville to Snoretown and lap over three hundred and four miles. I have this on good authority. Building sleep apparatus is one of the big industries of the United States.

To sleep well it is necessary to have the sort of bed that makes sleep possible and not the sort I had at the boarding house I infested in New York thirty years ago. It was a folding bed that had been in the boarding house business thirty years before I arrived, but it had been bought second-hand by the boarding house lady after it had had thirty years of private life in a poor but honest home. It did not push up from the foot like the old-style folding beds into the likeness of a wardrobe or highboy. This one was an older style than that. It pushed up to resemble a seven foot bookcase with a sateen curtain concealing the books that were not there.

"I think," said the boarding house lady when she showed me the room, "you will find this a comfortable bed."

"It looks comfortable," I said, and it did, and perhaps it was, but no one who ever slept in it was.

The drop-shelf, which was about five feet wide, was manipulated by two of the mainsprings of the late lamented town clock. They had been wound up tight and placed in tin cans which were open at one end to receive tag ends of bed sheets and bite them. These were placed at the top inside the upright or book-shelf part of the sleep destroyer, and from each spring pinion or doodad, as we specialists call them, a brass chain ran to the top, or outer, edge of the lowering-down or bed part of the patent dream preventer. The ends of these chains that were not attached to the main springs of the deceased town clock were fastened to the iron frame of the lowering-down part of the bed with especially made iron bolts. The "especially made" feature of these bolts was that they were made two inches long so that, after they were passed upward through the iron frame and chain link and the nut was screwed on, there was still one inch of tail end of bolt sticking up in the air. At the lower end of the bed the lady or gentleman using the bed placed his or her foot so that this end-of-bolt came between the big toe of the right foot and the toe next to it; at the upper end of the bed the bolt end engaged the top of the head, sandpapering it and removing dandruff while one tried to sleep. I do not remember having seen just this arrangement of bolts on any other bed and it seems to me useful because once the toes are wrapped around the lower bolt it is impossible to slip up or down in bed. Slipping down in bed might not matter much, but with the head pressed against the upper bolt any upward slip might open the cranium, thus exposing the brains to the night air and causing them to catch cold and sneeze. I would draw a diagram showing an accident of this sort, with "A" representing my big toe, "L" representing the lower bolt-end, "U" representing the upper bolt-end, and "O" -- or zero -- representing my brains, but I haven't the heart to cause so much needless suffering.

The method of using this bed for sleeping purposes I found to be the following: Having entered my hall bedroom and disrobed myself -- that means taking off my clothes -- I put them in a graceful loop over the arm of the gas-fixture. I then backed up against the closed folding-bed and opened my dresser drawer and took out a clean nightgown or -- as we say in Flushing -- slumber-shirt. This I donned, leaving nothing exposed but my head, neck, hands, wrists and beautiful alabaster legs and number nine feet. I then reached up and grasped the brass grasper at the top of the letting-down part of the folding bed and pulled outward and downward.

Immediately there ensued a noise similar to that when the six captives of the robber baron enter the dungeon clanking their chains, but the bed did not sing

"We are captives; captives we;

Captives in captivity;

Soon we will be mere remains

Rotting in our rusty chains."The rattling of chains was there, but not the song and dance; the only song the bed sang as its lowering-down portion slowly descended toward the floor was "Scree-ee-ee-eek!" I honestly confess that as that lowering-down part of the bed screeked and chain-rattled down I felt like the warder of the castle of Gotzpflanz when he lowered the drawbridge for the first time in five hundred years, the besieged having been without axle grease, machine oil or graphite for four hundred and ninety-nine of the five hundred years. When I lowered that bed the screech was so loud that gooseflesh came out on the surface of men seven blocks away and remained so permanent that they had to shave if off next morning with a razor. I called the bed my drawbridge to the land of dreams, because I was a poet in those days, and always working at the job, but after using that bed a few nights I quit, being a poet and became a pessimist.

As the lowering-down part of the bed came down the two angle-tin legs unfolded themselves from the cunning little interstices in which they had been cleverly hidden amongst the remnants of corrosive sublimate and deceased bedbugs during the day, and stuck out, thus being ready to touch the floor when the lowering-down process was complete. I then removed one of the trunk straps that held the bedding in place and swore gently at the one that would not come unbuckled. I next patted the pillow in place and turned out the gas.

I had had frequent warnings before leaving my old home in the West against the dangers of the great city, one being taking bad money and the other getting into a large walnut folding bed with knobs on it and having the lowering-down part of the bed close up during the night with me in it. It seemed that if the tension of those beds was set too taut -- say for a fat man and his wife -- and a slender lad like myself got into the bed it was liable to hiccough during the night and close up like a jack-knife, thus ending my promising career.

You can understand that after my father had warned me and I had said farewell to him and was in New York going to bed for the first time in a folding bed, I made sure that the folding-down part of the bed would not fold up and ruin me after I had got into it. I tried it by hefting up on the folding-down part of the bed and found it was perfectly safe against anything of that sort; I could not lift the folding-down part of the bed with both hands. So I got into bed.

Immediately the two angle-tin legs buckled into a knock-knee shape and the standing-up or bookcase part of the folding bed fell over on top of me, shutting me in like an oyster in a shell. From then on I slept on the top of the dresser, first putting the pincushion on the floor. But I never did sleep well on top of the dresser; my sleep there was intermittent and filled with hair brushes and celluloid combs.

That is why I say that to sleep well it is necessary to have a bed that makes sleep possible, or one that goes so far as to invite it. For a long life eight hours of honest unconscious sleep per night -- or say a total of fifty-six hours per week -- is necessary. I say this in spite of the well-known example of Napoleon Bonaparte who could get along with one or two hours of sleep in each twenty-four. I doubt it. I think that story is probably due to be filed away with the one about William Tell shooting the apple off his son's head, which has now been sifted down to the point where historians tell us he did not shoot an apple off his son's head, that he did not know how to shoot at all, that he had no son, that William Tell himself never existed, and that his son had no head. I do not yet claim that Napoleon Bonaparte never existed, and I will admit that he may have managed to stay alive with one or two hours sleep for awhile when he was a young fellow and built like a dried herring, but I have seen pictures of Napoleon made a little later and I have the same sort of hemispherical extension vest that he wore, and I'll swear that no man built that way ever did without sleep, if he could help it. The truth about Napoleon Bonaparte and his doing without sleep is that he was born in 1768 (some say 1769) and died in 1821 and was knocked to desiccated smithereens at Waterloo when he was only forty-seven years old because he was a chronic invalid, and died when he was only fifty-three.

I usually get to bed about one o'clock in the morning and am awakened about eight the same morning, making seven hours of sleep, but I also take a nap of an hour or so just after lunch, making my eight hours of sleep. This is a very regular schedule with me and I expect to keep it up for about forty more years; I expect to last forty more years because I sleep about eight hours a day. Personally I prefer the seven hours at night and the hour after lunch because the afternoon siesta aids the digestion and thus prevents Apollo from getting jealous of my shape. Unfortunately not all men in our country can sleep awhile after lunch, and I honestly believe it cuts down our efficiency when we cannot. We are always brightest and keenest for work just after breakfast in the morning, if we are well; the morning hours are when any man does his best work, and having a nap at noon gives the day two mornings.

And the other eight hours of a sensible man's day should be given to play -- genuine play and not play so-called. I mean real play, of the sort a boy goes in for. I mean play that includes games, and real play games.

Golf, for example, is a game and it is a mighty good one, but knocking the little white pill around the course because it necessitates so and so many miles of walking, and only because it gives the player that many miles of leg exercise, is not play. It is a form of work. If a doctor tells you "What you need is exercise; go out and play an hour of golf every day" your golf is not play; it is good honest work and ought to be done in the eight hours you devote to work and not in the eight you should give to sleep or the eight you should give to play. I used to play golf; I played golf for many years; I played golf before most of you ever held a club in your hands. I was a rotten bad golfer, one of the worst the world has yet permitted to live, but I enjoyed playing golf and so it was a game -- a play game. After eighteen or ninety-six years -- it began to seem like ninety-six toward the end of the period -- I did not care for golf any more. My score got worse and worse. I was so punk that I hated to go out on the course and exhibit my golf to my friends. I began to be one of those golfers who golf because it is supposed to be the proper thing to do, because everyone else is doing it. Golf -- and this is the honest word -- got to be the hardest and most annoying work I did. So I chucked it!

In something of the same way I have seen men go out on the course with a customer from Pennsylfornia or Calisylvania and spend whole afternoons working at golf for business's sake. You and I know that is not play -- it is business. Under such circumstances golf is not a game; it is a business operation exactly as going from Chicago to New York to close a contract is not a pleasure excursion, but a piece of work.

When a man begins playing a game with the primary purpose of keeping or regaining his health, of keeping or getting business, and when he plays a game at which he is so poor that he gets no fun out of it, that game is no longer play, but is work of the most annoying and irritating sort. Apples are good eating, and wax apples are good ornaments, but when a man eats a wax apple and tries to make himself think it is food he is fooling himself. Or is he?

I think probably I will take up throwing mudballs at a barn. I have the barn and its driveway is mostly mud, so the expense of the game will not be much and all I'll have to do will be to get a few limber green willow wands and a couple of other bankers or clergymen or retired millionaires to join in and share the sport. I know we will enjoy it. I have played thousands of games in my life, but I can't remember one of them that for pure delight beats sticking a ball of soft mud on the end of a limber stick and throwing the wad at the side of a barn. Using this method to see how far a ball of mud can be thrown has its good points -- and if you have never tried it you will be surprised to see how far a well-formed and properly weighted ball of mud can be thrown -- but there is something about the plap of a wed mudball against the side of a barn that delights the soul as nothing else can. In my young days there was considerable pleasure in chucking a wad of well masticated paper in such a way that it would hit some part of a schoolroom with a mushy plump and stick there, but it lacked the delightful sensation of the full-arm swing needed to send a mudball off the end of a throwing-stick.

I have tried other games -- dozens of them -- where hitting a mark was important as a part of the pleasure to be secured. I have shot with a rifle and with bow and arrow, and have knocked golf balls at the green. I have cast flies at the one bubble under which a trout should be lurking. I have shot my taw at the commies in the ring. I have thrown horseshoes at the peg. I have poked pool balls at the pockets. I have shot darts at a mark with a crossbow and I have shot BB shot at a boarding-house dinner bell. I have thrown cards at an upturned derby hat by the hour and night after night. I have thrown horseshoe nails at a knot in the sidewalk. I have, in short, used every kind of target that you can think of, but for pure satisfaction and pleasing results I don't know of any target that I like better than the side of a barn. It is about the only target I can hit. If you give me a mudball on the end of a stick and put me in front of the side of a barn, but not too far from it, I can usually hit that side of the barn or come dangerously near it.

That is the way the games we play should be. When a man finds he is so poor at a game that he always loses he gets little fun out of it.

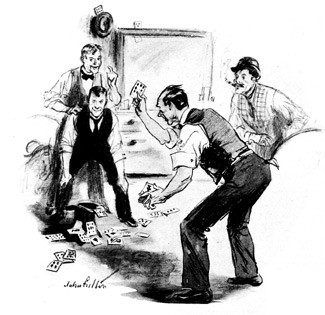

For a gentle indoor game that will not injure the weakest brain or tax the most delicate muscles I can recommend one I have mentioned -- throwing playing cards at a derby hat. This game, as far as I know, was invented especially for me at the boarding house I first infested upon coming to New York. When the card players there had won all my money -- it was $10.50 I think -- and I refused to consider card playing a game of play any longer, one of the men invented throwing cards at a hat as a game about suited to my mental capacity. In playing the game a derby hat is placed in one corner of a room, on the floor, upside down. A mark is made on the carpet about fifteen feet from the hat. The player then takes a pack of fifty-two playing cards in his left hand and, one by one, throws them at the hat, the object being to get all the cards into the part of the hat usually occupied by the head. This is a game that will not tax the brain of a tired financier or weary attorney at law beyond endurance, particularly if the player has a hired man gather up the cards after they are thrown at the hat. It will be found, after the fifty-two cards have been thrown, that some of them are behind the davenport in the next room and some in the hat. At first there will be more behind the davenport than in the hat.

In playing this game it does not matter which side of the card is held uppermost. Some of us threw the cards by holding them between the thumb and first finger and giving a sort of downward throw at the hat; others held the cards between the first and second finger and flipped the cards slightly upward. The player can try bending the cards slightly; this is permitted by the Constitution of the United States, but it never seemed to do my game much good. One of the little crowd that played this game night after night made a high record of something like forty-one or forty-two cards into the hat out of each fifty-two thrown; he could do this with fair regularity time after time and, as I never got more than eighteen cards in the hat, I finally decided that throwing cards was too much like work and I went out to Iowa and got married and moved out of the card-throwing zone.

The point I am trying to make is that every man who finds it possible and who wants to live long should play eight hours at some sort of games that he personally finds pleasant and enjoyable. When you play you should play and not indulge in what is, or has become for you, work under an alias. What the game is does not matter. You may like a game that is strenuous and invent one that consists of throwing blacksmiths' anvils over a house and catching them as they come down, and if you like it that is the game for you. Or you may like a sitting-down game like "fox and geese" or "old maid" -- that's your affair. But don't try to make yourself believe a "game" is play just because someone says it is a game, or because it is generally accepted that it is.

Work, no matter how we enjoy it, is not play. Work is work, and a very fair definition is that anything that is done for money is work. So is any play that is played for money, or to hold customers or because a doctor has told us to play it, or because we think a doctor would tell us to play it if we asked him about our health. Play is what we do when we are not asleep and from which we expect no money or direct health returns. A game is play into which some spirit of contest enters. You may play tennis and try to beat your opponent, or you may play solitaire and try to beat yourself, or you may blow wads of putty at a target with a bean-blower and try to better your own record; played for fun then games are games.

I remember when I was a young man and was employed as a bill-clerk in a wholesale grocery I took a great deal of pleasure in sitting on the high stool at my desk and cracking the big toe of my left foot. By letting my left foot hang free and then stiffening the big toe joints and then bending the toe I could make the toe crack like a cap pistol. The more I practiced this the better results I got and I felt sure that if I devoted myself to it faithfully I would eventually be able to crack my left big toe with a noise as loud as a revolver.

One day I turned around on my high stool and cracked my left big toe in an especially fascinating way, and I asked the firm's bookkeeper if he could crack his toe like that.

"No," he said with intense sarcasm; "I do not consider toe-cracking an accomplishment necessary for a bookkeeper."

A slam like that should have withered me, but it didn't. I merely refrained from mentioning toe-cracking to that bookkeeper from then on, and even now when I want a little harmless pleasure I rest my shoe on its heel and crack my left big toe a few times. The result is that the bookkeeper remained a bookkeeper during his whole career while I have become absolutely notorious in a great many ways. If I had been able to crack both my big toes as satisfactorily to myself as I could crack one of them I probably would be President of the United States now. It has added years on at the far end of my life, I am sure. And no one can dispute that, because I am not dead yet. The bookkeeper is eighty-two now, but that proves my contention; if he had taken eight hours a day for the purpose of playing pleasant games he might have been ninety or even a hundred by this time.

A man needs work and a man needs sleep, but a man needs play, too. To be happiest a man needs eight hours of play per day. Let us all, then, play as much as we can and try to get our full share of it. Let us remember the sad example of Adam, who had only one year of play and then had to go out into the cruel world and do nothing but work and sleep. As a result he was cut down at the untimely age of only nine hundred and thirty years. If he had taken a proper amount of play he might -- at the rate he was going when he started -- be alive today and be a brisk young citizen of five thousand nine hundred and thirty years and a useful member of the Mesapotamia Chamber of Commerce. Well, we have lost him and we must not mope around and repine because he is gone. Let us, rather, profit by his example and be warned. Let us try to get our fair share of play and maybe we will live to a hale and hearty old age of eight thousand or nine thousand years. I doubt if I can live quite that long, but I am going to try.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 5:38:58am USA Central