from Sunset Magazine

Starboard Ahoy!

by Ellis Parker Butler

When I responded to the loud knocking at the door and opened it I saw that Mr. Higby, my neighbor, was wildly excited, being quite red in the face. "There's not a minute to lose," he shouted, "that fool girl of mine -- that daughter of mine -- has eloped with some young idiot and, if I don't catch her before she marries the young whelp, she'll -- why, she'll be married."

He was talking so rapidly he was almost out of breath by this time but managed to continue, "My wife tells me you've got a car; do you know how to drive it?"

Though it was late in the afternoon I was still scantily clad in pajamas and dressing gown, for just before the loud knocking started I had taken portfolio 7S from the shelf, meaning to compare the entry I had made in my card system with the picture of the galleon Santa Isobel in that portfolio, fearing I had not been quite accurate in the number of portholes I had entered on the card devoted to that galleon.

"I'm afraid," I said pleasantly, in reply to his question, "that your wife is misinformed. The automobile to which she doubtless refers is not mine but the property of my sister, Cynthia, who is at present attending the Seventh Annual Convention of the Southwestern Theosophical Convention at Ultra Mare.

"However, won't you step in for a moment? I think there is a bottle of loganberry juice on ice, or, no! No, I believe I have forgotten to order ice. There is a card that I should have put in the window to attract the attention of the ice man."

"I don't care a hang about your ice," Mr. Higby shouted, "nor about your loganberry juice, nor about your sister. What I asked was whether you could drive that car."

"Ah!" I said pleasantly. "Evidently I misunderstood you. I thought you asked if I was the owner of the automobile. I think I may say that I have driven the automobile with quite a modicum of success. So, at least, my sister informed me after our trials, and she is not one to speak without due consideration. I do not, you understand, claim to be an expert with the automobile, but we returned with merely minor injuries to the superficial portions of the vehicle --"

"Great cats, you!" Mr. Higby cried. "You can drive the car, can you? That's all I want to know. Get it out and get your duds on and get going. There's not a minute to lose, I tell you."

"Dear me!" I exclaimed. "This is indeed serious. I have noticed your daughter and she seems a remarkably nice young person and not at all one who should be permitted to marry a -- as you phrase it -- whelp. If you will take a seat in the parlor and glance at a magazine you'll find there, I will be with you presently. I merely wish," I said, smiling at him, "to dress properly, putting on some trousers and other articles -- I don't suppose I would have time for a bath?"

"No!" Mr. Higby fairly shouted. "Don't I tell you the fool girl has run off with this fellow in our car? And taken our chauffeur along? Get a move on you, can't you? You're the only chance we've got to catch up with the two young idiots. Hurry!"

"I will! I will, indeed!" I assured him. "I shall just run up and put away the matter I was working on and be with you in no time at all."

"Don't put anything away. Hustle, you!" he urged me.

"It will not take me an instant, I said. "I am only sorry," I told him, as I paused at the door, "that our little chase of the runaways is not to be made by water. The automatically propelled land vehicle has never engaged my attention seriously, seeming to lack the romantic qualities of the wind-wafted vessels of the briny deep, of which I have made a most exhaustive study. Most exhaustive!

"As a matter of fact," I added, "I think I have one of the most complete collections of prints of wind-wafted craft in existence, together with what I consider a fairly complete library of the works of the best sea authorities, including Conrad, Melville, Lieutenant Dana, McFee, Captain Dingle and others, from which I have compiled a card catalogue of all the ropes, sails, masts and other portions of ships, including galleons, galleases, pinnaces, schooners, yawls, square-riggers and other craft, with their uses, so that I am familiar with them all."

"Get a move on, can't you?" demanded Mr. Higby in a most violent voice. "What do I care --"

"Certainly," I assured him. "I mean to make the utmost haste possible. I shall just take one moment more. I feel that I should set myself right in one matter. I would not have you think that I have spent so much time and labor in the study of sea-going wind-wafted vessels from mere idleness of mind. Quite the contrary, sir. As I often tell my sister Cynthia, my object has been quite shamelessly utilitarian. I mean to write a book -- several books. Romances."

"Look here!" exclaimed Mr. Higby rudely. "Those kids are running off to get married, I tell you! Every minute we lose they gain on us."

"Yes, in a moment," I said. "What I was about to say --"

Mr. Higby threw himself down on the sofa and groaned.

"What I was about to say," I said, moving a short distance into the parlor, "was that the returns from the works I have thus far written, including my 'Comparison of the Philosophies of Kant and Hegel' and my 'Brief Study of the Philosophy of Schopenhauer in Its Relation to the Mental Life of the Twentieth Century,' while well spoken of by the authorities, have not been great financial successes. Far from it, sir! It has seemed to me, for that reason, and because I have always felt within me the bubblings of a romantic nature, that my true work perhaps lay in the direction of romances of the sea.

By this I mean tales of a piratical nature, wherein would be included love motives --"

"She's the only daughter I've got," said Mr. Higby. "And she's gone -- gone! And this confounded idiot stands here blabbing at me!"

"I merely wished to make clear to you what I meant when I said it was a pity the young lady had not eloped by sea," I said with a little resentment.

"Well, that's clear now!" said Mr.

Higby, getting up and walking up and down. "Don't tell it all over again. Go and get your pants on. Get a move on you. I understand all about everything. It's all right; I don't object to it. But I beg you, I plead with you, I pray you -- hustle, can't you?"

"Yes, indeed," I said, and I went upstairs. In quite a reasonable time I was down again, fully clad. By this time dusk was upon us and Mr. Higby was on our front porch. As I went out he was pulling at his hair and cursing rather violently, although two ladies were also present. These I saw to be Mrs. Higby, who is a stoutish person, and Miss Pinderton. Miss Pinderton I had seen in the Higby garden with Mr. Higby's daughter, and I presently learned that I had been right in my conjecture that she was the tutor of the daughter in question. She was of the intellectual type, tall and of a serious mindedness of which I could not but approve.

"Do you really think I need go?" she was asking Mrs. Higby.

"Go? Of course, I think you must go!" declared Mrs. Higby. "I have no influence with that child, as you well know. To you she does pay some slight attention now and then. Certainly you must go, Pinny."

"I am never happy in an automobile," said Miss Pinderton.

"This is far, far from a joy ride, I assure you," Mrs. Higby told her. "It is not a pleasure excursion for any of us."

"And I have seen Mr. Duffington drive the automobile," said Miss Pinderton. "I'll go, if you insist, but this is going to be a miserable time for me -- most miserable."

"You'll go. Stop your talking," ordered Mr. Higby. "Get that car out, you."

Although this was no manner in which to speak to one who was really doing him a great favor, I realized that Mr. Higby was perhaps overwrought and said nothing. I went to our small garage and opened the doors and clambered into the automobile and in a remarkably short time had the interior mechanism palpitating in the proper manner, so that the automobile moved forward and out of the garage. At the exact spot where the excited Mr. Higby was standing I brought the automobile to a perfect stop.

"Eureka!" I exclaimed. "I attained a full-stop just where desired that time," but Mr. Higby was already hurrying his wife and Miss Pinderton into the automobile and was too busy to congratulate me.

"Get going! Get going!" he urged, and indicated that I was to turn to the right when I had achieved the street. Mrs. Higby immediately leaned forward with her arms on the back of my seat and began telling me the details of the birth, upbringing, idiosyncrasies and habits of her daughter Dorothy. "Get going! Get going!" Mr. Higby continued to urge, but my natural politeness could not allow me to ignore the good woman utterly. What she was telling me seemed to her of the utmost importance and I could see she was leading up to the matter of the elopement itself which was -- after all -- a basic element of the trip we were undertaking.

"I think I understand you," I said presently. "What you mean is that your daughter is of a naturally impulsive disposition --"

"I mean what I said," said Mrs. Higby. "That girl, from the day she was born --"

Mr. Higby here turned in his seat and, putting one hand against the back of Mrs. Higby's head, placed the palm of the other hand against her mouth, holding her thus in what must have been an uncomfortable position.

"Now, for great cat's sake!" he cried, "Get going!" and I did give my attention to the levers of the automobile. I felt a thrill of triumph as we turned into the street without damaging either the automobile or any of the fences on either side. Mr. Higby here released his wife's head and she continued with her description of the events leading up to the elopement, with explanatory notes making clear the reasons of her alliance with Mr. Higby and brief autobiographical details of her early life. To this she added from time to time short character studies of living and dead members of Mr. Higby's family. I turned to point out one particularly glaring false conclusion she was drawing -- that because Mr. Higby's father dyed his whiskers Miss Dorothy frequently danced all night at parties given by her young friends -- when Mr. Higby uttered a shout and desired to know if I would not watch where I was driving.

Fortunately there was no ditch or gully at that point and the automobile merely ran up a gentle slope. No serious damage was done to the automobile other than the elimination, so to speak, of one of the headlights. As the evening was now well upon us I lighted the remaining headlight and backed the automobile to the road again, and Mr. Higby made Miss Pinderton take the seat at my side.

"Now, for great cat's sake, Pinny," he said, "keep your eyes peeled, for this man is the craziest driver I ever saw. Get going, you!"

While I did feel like objecting to being addressed in that manner, I said nothing, for I knew that it might only lead to an argument and I was aware that time, as the realtors say, was an essence of this contract. What I mean is that I knew that haste was highly advisable. While Mrs. Higby had not been able to express herself as fully as she might have desired, I had gathered that she had found a letter addressed to Miss Dorothy by the young man with whom she had meant to elope, the letter setting the Wildwood Tea House as a rendezvous where they would meet and await the coming of the cleric who was to unite them, as well as some young persons who would serve as witnesses.

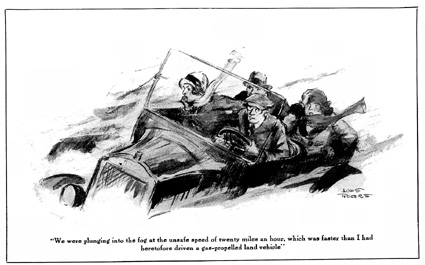

Through the deepening night we made excellent progress, for I find I drive an automobile much better when I can not see the distant impediments to our progress approaching me, and Miss Pinderton offered no distraction whatever, merely uttering little screams now and then as I negotiated especially trying curves or ran slightly off the road on one side or the other. Aside from this she merely held fast to the automobile with both hands, staring straight ahead in a somewhat tense manner. From the back seat Mr. Higby advised me, from time to time, to hit it up -- meaning increase our speed, if possible -- and I caused the automobile to travel rapidly, at moments reaching the speed of twenty miles an hour, which was considerably more rapidly than I had theretofore driven a gas-propelled land vehicle.

We were thus hastening along in the wake of the elopers when I encountered a phenomenon not uncommon in this neighborhood, but one that caused me considerable misgiving. I refer to a drift of fog across our pathway. The fog was coming from the right and was of no great volume, merely making dim the depressed length of road we were then covering, but it was accompanied by a considerable breeze from seaward, and this threatened nothing good as we proceeded. Indeed, my fears were justified, for when we had topped the next hill and were proceeding downward we ran into more and thicker fog, carried by a genuine wind.

"I do not fancy this," I said to Miss Pinderton. "It will increase the hazards of the trip to no mean extent," but she did not reply.

"Keep moving! Keep moving!" Mr. Higby called from the rear seat. "A little fog ain't going to bite you."

Keep moving I did, but with no little fear of ultimate consequences. Indeed, the road, as far as eyesight was concerned, was entirely eliminated one yard ahead of us, and it was only by watching for the whiter edges of it that I was able to know whether I was upon it or away from it. Above this bath of fog we could hear the wind continually increasing, and on the higher hills we, for a moment or two, passed out of the fog entirely, only to plunge downward into it again at the unsafe speed of eight or nine miles per hour.

"Hit it up, you! Hit it up, can't you?" Mr. Higby continually exhorted me. "This is not a funeral."

"It may be, if I do not drive carefully," I told him, but I did not in my heart believe what I said, for Miss Pinderton was now of the greatest aid to me, screaming whenever we reached an edge of the road and thus warning me in due time to turn to right or left. We thus proceeded no mean distance, when I became a little doubtful regarding the road we were traveling. I do not, I may say, drive an automobile as unemotionally as some. My technique, for some reason I can not understand, induces not a little alternation of haste and repression or, in other words, pause and progress. This, which I may call the norm in my driving, had now suffered from the addition of other unusual agitations, such as result when the wheels of an automobile encounter impedimenta of the sort often met just beyond a sign reading "Road Under Repair; Passable, But At Driver's Risk."

"This road," I said to Miss Pinderton, "must be under repair."

"Ye -- ye -- yes!" she replied.

"No it ain't!" declared Mr. Higby. "I was over it yesterday, and it ain't! It's good all the way to Wildwood Tea House. You've got off on a side road, that's what you've done."

"Yes," I admitted. "I think you are probably right. I think --"

"Lookout! Oh, be careful! A bridge!" Miss Pinderton here ejaculated, and I would have stopped the automobile instantly but I imagine I put my foot on the accelerating apparatus instead of on the one that would have brought the car to an instant halt. The automobile leaped forward, rumbling across a most trivially constructed bridge, hung in the fog an almost appreciable instant, and then thumped down upon some solid surface as I found the brake. At the same moment I saw a heavy wooden wall, not high but strong, in front of me, against which the headlight shone, and the bridge arose and hit the rear of the automobile and then clattered noisily and fell into water with a loud splash. Simultaneously two guns were fired close at hand and the fore end of the automobile hit the wooden fence and the headlight extinguished itself.

"I declare!" I exclaimed.

And, indeed, I had reason to do so. A most peculiar phenomenon was taking place. The automobile was rising at the rear and falling at the forepart, and then rising at the forepart and falling at the rear, quite as if it had been instantly fitted with rockers from a large rocking chair, and this it continued to do in a most unstable and distracting manner. At the same time I heard all round us various creakings and clatterings, but -- above all -- I heard the splash and gurgle of water.

Miss Pinderton, as soon as the automobile began to sway violently, had thrown her arms round me, clasping me close.

"Oh, where are we? Where are we?" she moaned in the most agonized voice I have ever heard.

It was now, with this noble fellow creature thus unnerved and throwing herself on me for protection, that my finest qualities came to the fore. Perhaps the pressure of her arms round my neck aroused me as the lion is aroused when its mate is wounded or in danger, for I appeared to see and understand our situation with the greatest clarity despite the fog.

"Do not be afraid, Pinny," I said, patting that portion of her anatomy that was nearest my hand. "I am here to protect you. This, I venture to say, is a situation with which I can cope, for -- if I am not mistaken -- we are on a ship or some similar sea-going vessel."

At this the poor creature became hysterical, bursting into high keyed and immoderate laughter.

"There now! There now!" I comforted her, but she still remained hysterical.

As you may well imagine, this sudden irruption of the automobile on to the ship -- if it was a ship -- with the advent of the swaying motion and the firing of the two shots so close at hand had thrown Mrs. Higby into consternation and had quite nonplussed her husband, particularly as the bridge or gangplank had whacked the backs of their heads in striking the back of the automobile, and Mr. Higby was now out of the automobile and cursing in the most ungentlemanly manner, while Mrs. Higby uttered one scream after another.

My first thought was that we had boarded, although unintentionally, some craft engaged in the smuggling of bootleg liquors, such as whisky or gin, and that the shots had been fired by the low scoundrels so engaged, they doubtless thinking we were officers engaged in suppressing their illegitimate traffic.

"Keep close to the automobile, Higby," I shouted, "and draw your pocket knife or whatever weapon you have on you. This is probably a rum ship."

I was already clambering out of the automobile, meaning to secure my electric torch, which was in the tool chest of the vehicle when there came six more shots in quick succession, with flashes of fire.

"Confound it!" Mr. Higby exclaimed. "I thought I saw one of the devils and let him have it, but it was this mast here. Look out, Duffington -- I ain't got a cartridge left in my gun."

"Crouch down," I whispered, "and be ready to oppose a rush. We must sell our lives dearly to protect the women."

We crouched and remained so a considerable time, Miss Pinderton still laughing hysterically and Mrs. Higby screaming at the top of her voice, but no one attacked us. It was then the swaying of the ship on the waves toppled Mr. Higby.

"Look here, you," he said. "I got a hunch. Feel of this rear tire -- it's as flat as a pen wiper. Those were not shots, they were these tires blowing out. You didn't see flashes, did you?"

"I did not happen to be looking in this direction," I told him, "my attention being focused on the fog immediately in front of the automobile. However, our situation is no less critical in any event. There are three possibilities. One is that a solitary watchman may have been left to guard the liquid contraband aboard this vessel, in which case he may have fired at us and then retreated into the obscurity. In that case he may even now be awaiting his opportunity to pop us off one by one, for I understand human life is held of little value by these rascals. The second possibility is that the entire crew of rascals is aboard, in which case they are undoubtedly doing what any sane malefactors would do, namely, putting to sea with all speed. The third possibility is that the ship has been temporarily abandoned, in which case it is to be feared that the bridge or gangplank was the ship's only attachment to the land and that we are now adrift and at the mercy of the deep. In that case my knowledge of ships will stand us in good stead and I will presently take over the navigation of it -- or her, as mariners customarily say."

With this I did the most sensible thing, arising to my full height and shouting in a loud voice.

"Ahoy! Ahoy!" I shouted, using the customary marine salutation. "Bootleggers, attention! We are not revenue officers or prohibition enforcers. We wish you no ill and our presence aboard is unintentional."

There was no answer to this, and Mr. Higby, who saw the wisdom of thus assuring the rascals that we meant them no harm, now shouted.

"Hey there!" he cried. "We surrender. We give up."

There was no answer to this, either. We called again but received no reply.

"In my opinion," I said, "the ship is deserted, and if anything our situation is even more serious. The attending circumstances are all such as indicate a serious marine catastrophe unless we make use of every effort to avert one. We are on a drifting ship in a dense fog with a severe on-shore wind and an unknown coast on our lee or landward quarter, and we have an inadequate crew and no charts. Under the circumstances I feel it my duty to take charge of the vessel."

"Well, for great cat's sake, do it, then," said Mr. Higby testily, "and don't stand here talking like a school teacher. I don't know anything about boats. If you can do anything, go ahead and do it, you."

"As long as I am in command, Higby," I said sternly, "you will address me as 'sir,' if you please. Go now and quiet your wife. Miss Pinderton, please!"

Miss Pinderton was still hysterical, but her laughter was lower now and seemed to be choking her somewhat, being mixed with exclamations such as "Oh, dear!" and "I shall die of this!"

I went to her side of the automobile and opened the door.

"If we all do our utmost," I said, "there need be no talk of dying. We must, however, all do that utmost. Kindly get out of the car, for I shall probably have to ask you to take the post of lookout at the bow of the ship."

"Yes, yes, Mr. Duffington," she said, trying to calm herself, and she clambered from the automobile while I secured the flashlight from the tool box.

"Now, my hearties," I said, "there is work to do. My plan is, briefly, this. The ship must be got under control. My studies of ships have shown me that, although it may seem a paradox, a ship may be made to sail almost directly in the teeth of a gale, the process being called close-hauling her, the sails being pulled to one side, so to speak, while the rudder is turned one way or the other, although I forget at the moment which way. It is necessary, however, in beginning this operation, that the ship have a steerage, so to speak, or forward movement, in order that the rudder may be affected by the waters passing from fore to aft under the vessel. I find it necessary, for that reason, first of all to raise or -- as the mariners say -- hoist the sails."

"Well," exclaimed Mr. Higby impatiently, "let's do it, then."

"Ah, but wait a moment, Higby," I said. "There is another thing to be ascertained first. Is this ship a square-rigger or a fore-and-after? Is she a brig or a sloop or a schooner? Are we on a large ship or a small ship. That is what we must, first of all, ascertain. If you will help Mrs. Higby out of the automobile I propose that we make a tour of the vessel now, so that I may know just what I am about."

Miss Pinderton was merely giggling now and then, having been able to that extent to control her hysteria, and I took her arm and led the way, Mr. and Mrs. Higby following close behind us. We had proceeded to the left of the automobile but a few steps when we reached a flight of stairs, and up these I led the way.

"It seems to me," I said, as I noticed the considerable height of this forward part of the vessel, "that this is probably a galleon or galleass, possibly one used by the early explorers and abandoned by them, and now used by these nefarious liquor smugglers, who are making use of every sort of craft."

Indeed, the certainty that the vessel was a galleon seemed even more evident until we had descended and had passed the automobile. Then I found that the stairs behind the main mast mounted to no such height as I understood they did in a galleon, and presently the presence of four masts and the narrow rear of the vessel satisfied me that it was a caravel, a very seaworthy craft in one of which Columbus made his voyage.

"This is extremely fortunate," I said, "for no more satisfactory vessel for rough weather can be imagined. We will now hoist a few of the sails."

I then pointed out to Mrs. Higby the steering apparatus and explained the meaning of "starboard" -- commonly pronounced "stabbard" by mariners -- and "labbard" or larboard, which is the other side of the ship, for I meant to place the steering of the ship in her care, calling out to her "Starboard, ahoy!" or "Larboard, ahoy!" as I wished the ship pointed one direction or the other.

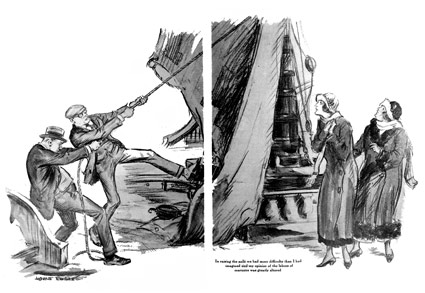

In raising the sails we had far more difficulty than I had imagined and my opinion of the labors of mariners was greatly altered. The fog interfered with a proper view of the ropes, which are, I believe, in nautical language, called hawsers or buntlines, and a number of tables and chairs on the deck were considerably damaged when the sails were finally lofted. Mrs. Higby now took charge of the steering apparatus and I stationed Mr. Higby by the masts in the middle of the caravel, instructing him to untie all hawsers and buntlines and lie flat on the deck if I shouted that a squall was upon us, and with Miss Pinderton I went to the upstairs of the bow of the vessel, to observe our course. The hoisting of the sails seemed to cause the caravel to sway far more than before, and the waves splashed violently against her, even sending spray to where we were.

"I hope the spray does not annoy you," I said to Miss Pinderton. "I fear it does." I then shouted to Mrs. Higby, "Ahoy, steerslady! A little more stabbardish, if you please!" my intention being to veer off somewhat and lessen the splash, but the effect seemed inconsiderable. "Ahoy, steerslady! Kindly labbard the helm somewhat more than it was before I asked you to stabbard it," I now called, and Mrs. Higby replied, "Yes, sir!"

Miss Pinderton seemed to me to be shivering with cold, the fog being excessively damp, and I moved closer to her in order to shield her from the fog-laden wind, and put one arm across her shoulder to steady her chair against the quite violent swaying and tossing of the caravel. "Mr. Duffington," she said, when her shivering had lessened, "I think you are just wonderful. The way you have managed all this --"

"Not at all, Miss Pinderton," I said. "Indeed, had it not been the thought of your incomparable self that urged me, there is no telling what I might have done."

"Really," she said, "you are what Dorothy would call a 'scream,' Mr. Duffington. I never imagined there was a man like you."

"Nor I a female like you, Miss Pinderton," I said.

In this manner we conversed quite a while, growing constantly more pleasantly acquainted and ere long I was telling her that I had hoped all my life to meet some one such as she, and she confided that she had quite despaired of finding a male of my type until she saw me in my garden one day. Thus we soon found a mutual esteem and I was holding her hand after we had spoken a few words regarding the place and time most appropriate for our wedding when the swaying of the caravel lulled us both to sleep. I was awakened suddenly by a shout from Mr. Higby, and starting up with considerable guiltiness I saw the last of the fog vanishing and the land within a few feet of us on one side.

"Ahoy, steerslady!" I shouted. "Right! Right! Right!"

"Oh, cease," cried Mr. Higby. "Don't be an ass any longer than you have to be."

Miss Pinderton giggled.

"Don't mind him, Duffie," she urged me. "You and I know."

The words were enigmatic but I did not try to find their meaning then, my calm being considerably disturbed by the evidence that I had been mistaken regarding the danger in which the caravel had been. In fact, now that we could see clearly, it was evident that the staunch little craft had been firmly anchored, fore and aft, with four exceedingly heavy ropes extending from port holes in the lower portion of the vessel. We were no more than ten feet from the shore and the bridge or gangplank was still floating in the water between us and the dock, being unable to float away because of two other heavy ropes that held us to the dock.

"We must have slept quite a while," I remarked to Miss Pinderton, there seeming nothing more appropriate to say.

"We certainly did," she said, blushing. "It's full morning. Well?"

"The light of day," I said, smiling at her, "does not change my opinion of the advisability of our early union."

"Nor mine," she said, looking up at me with a fondness no man could observe with anything but happiness. "I think any woman would be safe with you, Duffie. You managed this whole thing so wonderfully. I knew the very minute you began to delay Mr. Higby at your house that you knew it was your nephew Charles with whom Dorothy had eloped, and that the affair had your approval. Charles is such a fine boy, really."

"Oh, yes -- yes!" I said hastily. "He is indeed a fine boy."

"But not as clever as you are, Duffie," she said, patting my hand. "The way you wiggled the automobile from side to side on the road, holding us back to give the young dears a chance! And pretending you did not know how to drive! But the moment you took the side road beyond the Hetmeier's place I knew you were up to some cleverness." I coughed gently.

"But even then I only thought you were going to pretend we were lost in the fog," she continued. "I never imagined you had thought of anything so amazingly clever as the caravel. To tell you the truth, Duffie, I did not think of the caravel at all. Of course I knew that Jane Sprood had bought the caravel after the motion picture company had finished with it, and that she had made a floating tea room of it, and that it was at the end of this side road, but that you would drive the automobile on to it and then make the Higbys believe we were at sea, really! You don't wonder I got quite hysterical, do you?" "No," I said. "No, I do not." "I've always said," she declared, leaning toward me, "that rough noisy men like Mr. Higby are not the safest in emergencies; the brainy men -- thinkers, Duffie -- are always best at all times."

"Ah -- ahem!" I said, not thinking of anything more appropriate to say. As a matter of fact I was wondering what my sister Cynthia would say when she returned and learned that her automobile was aboard a caravel, with two blown-out tires. I did not have to wonder what she would say when she learned I had assisted the elopement; she always did admire Dorothy Higby. In fact, I did not wonder at anything long, for Mr. Higby was now rapidly disappearing up the road and Mrs. Higby had her back to us, shouting some directions after him. A peculiar braveness took possession of me and I drew Miss Pinderton to me. I kissed her on the cheek. I think I may say she nestled then; she distinctly nestled.

"Kiss me again, Captain," she said gently. "Kiss me again, a little to starboard."