| ||

| ||

from Red Book

Cousin May

by Ellis Parker ButlerOn the morning of the sixth of August, Roger Murchison took his seat at the breakfast table and drew the pile of mail toward him, while Miggs, his faithful butler, prepared two slices of toast on the electric grill on the sideboard. This Roger Murchison was not at all the same Roger Murchison that had breakfasted at the same table a few months before. It is true that he still wore the shabby brown dressing gown and floppy slippers; but he was now a brisk, cheerful man -- a man interested in life and not afraid of the night. For several weeks Roger Murchison had been sleeping soundly. His eyes were bright, and many of the lines of care had been eliminated from his face by the increasing fullness that told of a good appetite.

"Miggs," he said cheerfully to his butler, "do you think this establishment could manage a slice of nicely browned ham this morning?"

The old butler's face glowed with delight as he turned toward his master.

"I am quite sure it can, Mr. Roger," he said; "and if I may venture to say so, it gives me great pleasure to have you ask for it."

"Thank you, Miggs," said Murchison. "I do feel like a boy again. My Graft Syndicate has been a success, has it not, Miggs?"

"I am obliged to admit that it has, sir," said Miggs. "You sleep well every night, now, sir, I am glad to say."

"And you did not think much of the idea, did you?" said Roger Murchison a bit teasingly.

"I must confess I did not, sir," said Miggs, turning the toast, "and I am not calm in my mind about the business, even now, Mr. Roger, if I may make so bold."

"You mean you fear my three grafters may lead me into trouble I do not expect?" said Mr. Murchison.

"I believe that is what I mean, sir," said Miggs respectfully. "The present association with persons of the criminal classes may not be easy to bring to an end. If you will permit me to say so, Mr. Roger, I very much dislike the idea of giving those persons more room in this house."

Roger Murchison smiled, but the smile was not entirely confident. There was much sense in what Miggs said. Not long before this, Roger Murchison had been a sufferer from insomnia in its worst form; he could sleep neither by day or by night, and felt himself doomed to madness or a suicide's fate because he could not withdraw his mind from its endless contemplation of the mystery of the Markham Vase -- known as the Vase of Apollo of Corinth. This, the ancient ritual vase of the Temple of Apollo of Corinth, pictured twenty-two of the twenty-four dancing figures, each typifying one of the twenty-four rites of the worship of the Corinthian Apollo; but a missing portion of the vase left two of the figures to conjecture, and it was by trying to imagine these two figures that Roger Murchison had brought himself to sleeplessness verging on madness, for he was a student of such subjects and an authority comparable only with Gerking of Berlin and Pinzucci of Florence.

The days, when he was busy with his investigations in his study, had not been so awful; but the sleepless nights of vain thinking were beyond bearing, and it was in his desire to drive away the thought of the vase by putting into his mind some other problem that Roger Murchison conceived the idea of hiring three persons to attempt to bunco him, hoping that by trying to prevent their success he would give his mind the new problem it needed.

Choosing quite at random three persons from the many who wrote him begging letters, Mr. Murchison -- a bachelor -- had contracted with them to try to get money from him by any fraudulent means. At first Rosa Lind -- who posed as a queen of graft, Red-line Rose, but who was only a stenographer who had failed as a stage dancer -- and her two partners, Mr. Skink and Mr. Tubbel, had been but poorly successful; but they had recently contrived to bunco Mr. Murchison out of fifty thousand, and then one hundred thousand dollars; and as he had agreed to double any amount they won, his loss was a full three hundred thousand -- a nice sum, but trifling to a man with over twenty-five millions, since he was now sleeping well and all danger of madness and death seemed gone.

The effect of their two successes on Rosa Lind and her confederates, Mr. Skink and Mr. Tubbel, had been noteworthy. While Mr. Skink and Mr. Tubbel had been eager to throw up their extraordinary task, they were now eager to continue. In Rosa Lind the difference was even more marked. While Roger Murchison had fallen deeply in love with her and she had come to admire him sincerely, her graft successes had made her eager to do still greater things in the bunco line.

It was in this eager spirit that Rosa Lind had asked Roger Murchison to set aside for her use two additional rooms on the second floor of his Fifth Avenue house, where she already had one to use as headquarters for the Graft Syndicate, and it was this request for more rooms that disturbed Miggs more than aught else. Her plea granted, Rosa Lind had promptly fitted the two additional rooms with office furniture, and on the doors of the three rooms, in gilt letters, appeared the legends, "Miss Lind," "Mr. Skink" and "Mr. Tubbel." Not only had this been done, but each day there now assembled in the three rooms enough persons to constitute the force of a good-sized business organization -- some twenty in all. The extent of Rosa Lind's intended operations against Mr. Murchison's bank account might have been indicated by the fact that eight typewriting machines were clicking continuously, while each room had its own telephone.

When Roger Murchison had viewed these preparations, he had felt a glow of pleasure such as a chess wizard feels when he sees the boards set for the match in which he is to pit his skill against the combined skill of a dozen expert opponents.

Murchison opened his mail while Miggs busied himself with the preparation of the eggs and ham. A few ordinary begging letters Murchison put to one side. The next letter held his attention. It purported to be from his uncle in California, saying that Roger's cousin, a girl of twenty, was coming to New York, and asking whether it would be convenient for her to stop at the Murchison home during her stay. If not, Roger's uncle suggested, Cousin May would probably stop with Roger's aunt Ann Warker.

"Cousin May!" said Murchison to himself, and smiled. "My dear cousin May is probably one of the strings of my grafters' bow."

The next letter bore an Italian postmark and stamp, and seemed to be in the hand of Professor Pinzucci of Florence, and dealt with the Markham Vase. The site of the Temple of Apollo at Corinth had been located, and it was desired to form a company or secure a fund to excavate on the site on a chance that the bit of shard showing the two missing dancing figures might be found. As the war had left Professor Gerking of Berlin penniless, Professor Pinzucci was appealing to Mr. Murchison. Between fifty and one hundred thousand dollars would suffice.

"Do I see the hand of my grafters in this?" queried

Murchison, and he put the letter atop that of his uncle. One by one, as Murchison opened the letters, he placed them on the same pile. Each and every epistle might be the opening wedge for the next bunco operation planned by Rosa Lind, and yet none might be. Roger Murchison gathered the letters into two great bundles and crowded them into the two pockets of his dressing gown for later and mature study. The game was growing interesting, for each day brought its score of events and epistles. He attacked his ham and eggs with enthusiasm.

The telegram announcing the departure from Pasadena of Roger Murchison's cousin May was of the sort known as a night letter and was handed to Mr. Murchison at breakfast some few days later. The envelope containing it had been placed by Miggs on top of the morning's pile of mail and was the first thing opened by Roger Murchison.

"My cousin May will arrive five days from today, Miggs," Roger said. "She will stop here. I have asked Aunt Ann to be with us during my charming cousin's visit. I say 'charming,' Miggs, because I have it on the best authority that she is indeed charming."

"I am sure she must be so, sir," said Miggs.

"Charming, but I do not know what else," said Roger, "for this, I believe, Miggs, is the day of the vamp, as I have gathered from the papers. I do not mean to be vamped, Miggs."

"And quite a proper reluctance, sir," said Miggs. "I have feared that the young lady might be in conspiracy with your grafters, sir, if she is indeed your cousin."

"On one point I have protected myself," said Roger. "I have had telegrams from eight entirely dependable ladies of Pasadena assuring me that my cousin May does indeed mean to come to New York, describing her most minutely, and promising to wire me of her departure from Pasadena. Do I hear the bell, Miggs?"

While Miggs hurried to the street door, Mr. Murchison opened more of his mail. A letter from the United States counsul at Florence assured him that Professor Pinzucci had not written the letter regarding the proposed excavations for the shard of the Markham Vase, and that it must have been the work of forgers. Of the remaining letters, a half-dozen might well be opening wedges for new bunco operations, and a half-dozen others were from lawyers, financial concerns and others telling Roger Murchison that letters previously received must have been the work of frauds or criminals.

Murchison chuckled. He felt mentally alert and capable of checking any move made by Rosa Lind.

When Miggs returned, he bore eight telegrams. All were of the same tenor, announcing that May Wiltson had left Pasadena en route for New York.

On the fourth day following the receipt of the wires saying Miss Wiltson was on her way East, Mr. Murchison, at breakfast, gave Miggs his final instructions regarding the arrangements to be made for her entertainment.

"Miggs," said Mr. Murchison, as he paused half way in the consumption of the generous slice of ham in which he had been indulging of late, "this ham seems to have a peculiar taste."

"Indeed, sir?" replied Miggs. "I had a bit of it myself this morning and it seemed quite proper, sir."

Murchison laughed.

"I'm getting just a little too suspicious, perhaps, Miggs," he said. "I look for the work of my Graft Syndicate even in ham and eggs."

"Yes sir," said Miggs. "No doubt but what you have cause to be on your guard, sir."

As usual Mr. Murchison carried his mail to his study to assort and consider at leisure when he had finished his breakfast. Hardly had he entered the room, which adjoined the one used as an office by Rosa Lind, than there came a tapping on the door. When he gave permission, the door opened, and Rosa Lind entered, accompanied by the tall, thin Mr. Skink and the preposterously short and fat Mr. Tubbel.

"Ah, Miss Lind!" Roger exclaimed. "Nothing wrong, I hope."

Rosa Lind sank into the chair opposite Mr. Murchison, leaving Mr. Skink and Mr. Tubbel to find seats or not, as they chose. As he looked into her face, Roger Murchison felt with renewed delight the beauty of her eyes.

"Nothing wrong," said Rosa Lind, smiling slightly. "It is only that I have heard through your housekeeper that a young lady -- your niece --"

"My cousin, not my niece." said Murchison.

"Your cousin? -- That your cousin, then, is coming here," said Rosa Lind. "I can well see that the presence in your house of myself and the many people I have found necessary in my work might be --"

"And I say," Mr. Skink broke in, "that an agreement is an agreement. You offered us these rooms --"

"And we've a right to them," puffed Mr. Tubbel. "I say that to make a man move out of his private office just because a niece or a cousin is --"

"Be still, Tubby," said Miss Lind. "You will let me do the talking, if you please. I have come to offer, Mr. Murchison, to transfer the headquarters of the Graft Syndicate elsewhere temporarily if you so desire."

"That is kind, Miss Lind, very kind," said Roger with feeling, but with just a suspicion that something might be hidden beneath her offer. "If you will let me consider the matter for one moment --"

He felt a bit drowsy and rising to stir his faculties, walked over to the window. His eyes idly rested, then, on the facade -- in the monotonously prevalent brownstone of the older New York -- of the home of his opposite neighbor. There must be, he argued, some trick in this offer of Rosa Lind's. What it might be he could not at the moment fathom; but trick it must be, unless, indeed, Rosa Lind did indeed care for him and what might be thought of him. He turned from the window. She was looking up at him, smiling, and Mr. Skink was just dropping into a chair, while Mr. Tubbel had taken from his pocket a match to light a cigarette he had already placed in his mouth.

"I think --" said Roger Murchison. But at that moment the cloud of drowsiness which had been gathering seemed entirely to envelope him. He put his hand to his eyes and gasped, but the next moment all seemed clear again. Something seemed to have happened, however -- which was really not at all strange, for as a matter of fact several days had happened, and various interesting events. He came to his senses however, lying on the floor as if he had merely suffered a momentary faint; and as he opened his eyes, Rosa Lind and Mr. Skink sprang from their chairs; and Mr. Tubbel puffed and panted toward him. Even before he could scramble to his feet, the three had grasped him by the arms and were helping him to his chair.

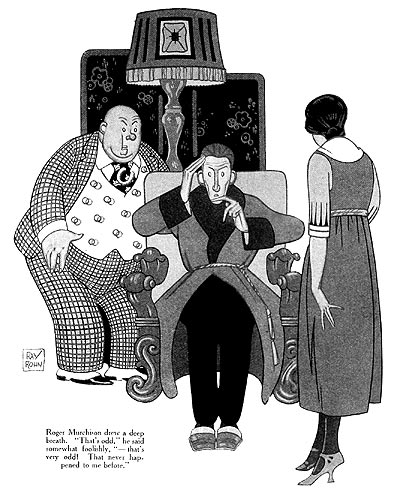

"A glass of water, Skink," said Rosa Lind sharply; Mr. Skink went out of the study, and before she could say more, Roger Murchison drew a deep breath.

"That's odd," he said, somewhat foolishly, "-- that's very odd! That never happened to me before. Things went black; I fell, didn't I?"

"But how do you feel? Are you all right now?" Rosa Lind asked.

"Quite all right," he said.

"Had we not better send for a doctor?"

"No, I'm quite myself again. Thank you, Skink; this water will quite restore me. And now, as I was saying a moment ago. I think there is no necessity for you to move your headquarters from this house. I prefer that you should stay here. If my cousin shows any interest whatever, I may tell her you people are a staff I have gathered in connection with my investigation of the ancient Greek vases -- which," he added smilingly, "is more or less the truth."

"Thank you, Mr. Murchison," said Rosa Lind. "But if you think best to change your mind, we will go at any time." And with Mr. Skink and Mr. Tubbel, she left the study.

Murchison, left alone, sat in silence some minutes, trying to test any inward sensations he might be feeling, but he felt none except a rather pleasant lassitude and an unaccountable hunger. He put out his hand for his pile of letters and yawned luxuriously as he took the first letter from the pile. With it open, he stared at it lazily. He was too delightfully weary to read it. He arose and walked to the window, looking out upon the Avenue until he wearied of that sight. As he returned to his table, he let his eyes rest upon his priceless collection of Greek vases, the vast number of which filled the cabinets that lined the walls. A vase with a Hebe filling a cup depicted on it reminded him again of his hunger, and he pressed the button that summoned Miggs.

"Miggs." he said, "I am hungry."

The old butler bowed.

"Yes, Mr. Roger," he said, quite as if his master habitually became hungry immediately after breakfast.

"Miggs," said Murchison, "I feel as if I had not eaten for a week."

Miggs seemed to hesitate.

"But you have, sir," he said with what seemed unnecessary earnestness. "Not as heartily as usual, perhaps, sir, but sufficient, if I may say so, amply to sustain life."

With these remarkable words he went about his business, which was to get Roger Murchison something to eat.

When Miggs had removed the tray, after his master had emptied the coffee cup and the dishes, Murchison went through his letters, making notations on some and tossing others into his wastebasket, and answering some in his customary longhand, and then strolled to the window looking down at the Avenue, as he loved to do when perplexed.

As he looked, an automobile -- a limousine of value -- stopped before the brownstone mansion opposite, and to Roger Murchison's unbounded surprise, Mr. Slunk and Mr. Tubbel emerged from the car, closely followed by a young woman deeply veiled. Mr. Skink and Mr. Tubbel seemed to be aiding her with chivalrous care, but Mr. Murchison, from his window, could see that they grasped her arms with all the strength of the fingers, and they hurried her up the steps of the stoop of the house opposite. The door opened to receive them, and the house opposite swallowed all three. In the moment before the door closed, Mr. Murchison saw Mr. Skink cast a quick glance to the window, but Murchison had hidden himself behind the curtain and felt sure he had not been seen.

"So that is it!" he said grimly, for the size and general proportions of the young female prisoner were the same he had been advised were those of May Wiltson, his California cousin. "So that is it! No wonder Rosa Lind was willing to make offers of removal. My chief of grafters is a gentle jester! And I suppose," he added to himself, "this will be a case of ransom. Clever indeed! They well imagine I would not care to have Cousin May's father know his daughter was stolen from under my eyes. But --"

He stopped short and put his hand to his forehead.

"But she is not due till tomorrow!" he cried with a sudden sensation of all the world going wrong. "This must be some trick or --"

Gazing through his curtains at the house opposite, a detail that he had not grasped before now caught his eye, and he bent forward, hardly breathing. The number over the door of the brownstone mansion opposite was not the number of the house of the neighbor across the street from his own mansion!

The number, if it had not been tampered with, was that of a house some blocks farther north on the Avenue! Murchison turned and surveyed the room in which he stood. It seemed, in every detail, his own study in his own house, with every precious vase in the place it had always been.

He went to the door and threw it open. This was not his house! The long hall, which in his own house was softly carpeted, was bare except for a strip of cheap matting. Murchison turned to the room that had been Rosa Lind's office. No name was on the door; and when he opened the door, the room was empty, but for the dust and rubbish that usually are the mark of long-vacated rooms.

Murchison walked down the stairs to the lower floor. Instead of the somewhat old but elegant furnishings of his own home, nothing but bareness met his eyes, except that at the street door was one cheap wooden chair, and on this sat the man he had known in one of the Graft Syndicate's earlier operations as Dan Fogarty.

Dan Fogarty looked up as Murchison approached him. In his hand Dan Fogarty held a wicked club made from a billiard cue. He moved this slightly as Murchison approached him, getting a better grip on it, and Murchison saw that the portion used as a handle had been wrapped with tire-tape. Nothing gives a safer gripping surface.

"Morning," said Fogarty briefly. "It's all right," he added as Murchison glanced at the club. "You have the run of the house, upstairs or downstairs, but keep away from doors and windows down below here. Back door is watched. Forman is there."

"Where is Miggs?" asked Murchison.

"Miggs? Him you ring the bell for? He's in the pantry I take it."

"Thank you. I'm a prisoner here, I suppose?".

"Looks like it," said Fogarty.

Murchison turned and went toward the pantry. As he neared it, he heard Miggs moving about, and the clink of spoons and metal ware. Evidently Miggs was engaged in preparing the next meal.

"Always faithful, always dependable," said Murchison to himself, and opened the pantry door. The elderly butler turned.

"Well, Miggs?" Murchison said.

"Yes, Mr. Roger," said the butler, putting down the culinary instruments and assuming his customary respectful attitude. "Just getting a bit of luncheon ready, sir. I hope you find yourself none the worse for what has happened, sir."

"I'm all right," said Murchison. "Miggs, how long have I been here?"

"Some days now, sir, I regret to say, sir," said Miggs.

"I see!" said Murchison. "I was given some sleeping potion, I suppose, and all this has been done while I have been unconscious. Very clever. And very considerate of my grafters to allow you to come with me. Were you drugged also, Miggs?"

"Why, no, sir," said Miggs. "I am sorry to say, Mr. Roger, I was not drugged."

"I see! You came voluntarily."

"In a manner of speaking, yes, Mr. Roger."

Roger looked at the butler sharply.

"Do you mean to tell me, Miggs," he asked, "that you are a party to this outrageous affair?"

"I fear that I shall have to confess that I am, Mr. Roger," said Miggs with distress. "I trust you will think no worse of me, sir; I meant all for the best, Mr. Roger. I beg you to believe that I have loved you like a father, ever since the day you were born, Mr. Roger. To see you sleepless, night after night, and nearing insanity, quite broke my heart, sir. And the Graft Syndicate did change all that, sir. It seemed a God's providence, Mr. Roger; and loving you as I do, I thought I could not do you a better turn, sir, than to give Miss Lind such aid as I could, when the occasion presented itself."

Murchison studied the honest face of his faithful butler and ended by smiling. With the annoyance that came from the knowledge that even Miggs the faithful had been corrupted, came also a delight in the thought that Rosa Lind's clever mind had accomplished even that miracle.

"I forgive you," he said; "and I could forgive you even more eagerly if this affair did not involve a young woman whose father placed her under my protection. This is an abduction affair, is it not? Miss Wiltson has been abducted; is that it?"

"Yes, Mr. Roger," said Miggs.

"And I am secluded here, and allowed to know I am secluded, so that I may know Miss Wiltson's father cannot reach me by hook or crook. Very pretty! And soon the threat will come that May Wiltson's father will be notified of her disappearance and my culpable carelessness unless I pay some outrageous amount."

"I believe that is the general idea, sir." said Miggs, "but I have a letter for you here, sir, that doubtless explains all."

From his pocket he took an envelope which he handed to Roger Murchison. The promoter of the Graft Syndicate tore open the envelope and read the letter. It said, in more specific terms, what he had already said. Miss Wiltson had been met at the train and was now in safe custody and would be held captive until Roger Murchison paid the sum of two hundred thousand dollars ransom.

"Excellent!" said Murchison. "Most cleverly planned and executed."

"I think so, indeed, sir," said Miggs. "I have found the grafting parties exceedingly keen of mind. If I may venture a suggestion, sir, it is that you pay the sum mentioned immediately. I understand, sir, that fifty thousand dollars are to be added for each day you delay."

"That's it, is it?" said Murchison, smiling. "Well, Miggs, this graft business is a game, and this particular hand is not played out yet. I may win this one before the last card is played."

"Perhaps, sir," said Miggs, "but I would not be too confident of it. If it is not impertinent, sir. I would advise you to remember the ham you did not greatly fancy the taste of. I was guilty of drugging it, sir; and as I am to be your only source of food, sir, you can quite see that if you become too active, I shall be obliged, begging your pardon, to put you to sleep for another week or two."

Murchison, thrusting his hands into the pockets of his brown dressing gown, smiled at the butler.

"Just so!" he said. "And quite right, since you are paid to do that by my opponents. The only question is, Miggs, how much are you to receive for it?"

"The sum of ten thousand dollars was mentioned, sir," said Miggs.

"Very tidy," said Murchison. "But I, Miggs, will give you twenty-five thousand dollars to desert my opponents and to help me instead."

Miggs wiped his hands carefully on a napkin and held his right hand toward Murchison.

"If it does not seem improper, Mr. Roger." he said, "I would like to shake hands on that, sir, to make it a binding bargain."

Murchison clasped the faithful fellow's hand.

"Thank you, sir." said Miggs. "And I have no compunction about playing false to the grafting parties, all being fair in the bunco business, when hands are not shaken, which they neglected to do."

With Miggs on his side, Roger Murchison felt that he had a fair chance to defeat Rosa Lind, for the butler was allowed to leave and enter the house at will. Murchison felt, too, that his knowledge of the place of May Wiltson's confinement was a strong trump card in his hand; but before deciding on any course of action, he went to his improvised study to think the matter over most carefully, for he had now no mean opinion of Rosa Lind's activities.

The simplest procedure. But to do so, when his grafters were only following the rules he himself had laid down, would be pitifully cheap. Moreover, to call in the police would mean publicity and would perhaps jeopardize Miss Wiltson's reputation.

With the police put aside as out of the question, Murchison's next thought was of Alonzo Herris; and in Alonzo Herris, for over forty years the family lawyer of the Murchisons and a safe, elderly man, Roger saw the man to use in defeating the Graft Syndicate. He dipped his pen in ink and wrote, carefully and with exactly chosen words, the instructions he wished Alonzo Herris to follow. As far as possible he left no contingency uncovered.

In signing the letter Roger Murchison made sure his instructions would be obeyed, and did so in a most simple manner. Over the sixth letter of the name Murchison, he placed two minute dots, instead of the customary single dot.

The use of this double dot had been agreed upon by Murchison and Alonzo Herris when Murchison first undertook maintaining a private graft syndicate, and the idea had been that of the wise old lawyer.

"If you go into this bunco affair." he said, "forgery will be one of the means your grafters will most likely use. Against that we must have some protection. We must have some secret mark, to be used only when our commands are of the utmost importance and to be unfailingly obeyed."

It was the signature with this secret mark that Murchison used in signing the letter, and this letter he gave to Miggs to convey to Alonzo Herris. He gave the letter to Miggs when the butler brought the luncheon, and immediately after luncheon Miggs left the prison house with it.

For the greater part of the afternoon Roger Murchison paced the floor of his study nervously, waiting for five o'clock, and at exactly five o'clock he was delighted to see three large automobiles turn out of the avenue traffic and stop before the brownstone house opposite, and he smiled as he saw the elderly lawyer in the first car of the three, and the husky, businesslike appearance of the dozen men in that and the other cars.

Alonzo Herris mounted the steps to the door of the house opposite and pushed the bell button. The man who opened the door, Mr. Murchison saw, was Mr. Carlo Dorio Skink. He could only guess at the short confab that ensued, but that it was satisfactory to Mr. Herris he had no doubt, for Mr. Skink closed the door, only to open it again a minute later and admit the old lawyer and all the husky men Mr. Herris had brought with him.

"Check!" said Roger Murchison. "It is your move now, Rosa Lind."

When the door of the house across the way opened again some minutes later, Mr. Herris was the first to come forth, but clinging to his arm was the veiled young woman Roger had seen enter the house. The lawyer and the lady were closely followed by the husky protectors, and all entered the cars and drove away, while Rosa Lind -- he could not be mistaken -- stood at a window and watched from between the slightly parted curtains.

Just before she let the curtains fall together, Rosa Lind cast one glance toward the window where Roger Murchison stood.

"Checkmate, my dear," said Roger Murchison, but even as he said it, he thought he saw a look of triumph -- a merry, teasing look -- on Rosa Lind's face.

On the top floor of the house opposite that in which Roger Murchison was a prisoner, the honest Miggs lay on the bare floor of an empty room, a gag in his mouth and his hands bound securely behind him.

Shortly after the departure of Alonzo Herris with the veiled lady, Horatio Tubbel -- panting from the exertion of climbing the stairs -- opened the door and released the honest Miggs.

"It's all right now, Miggs," he said, puffing at each word. "It's all over. You can go now."

"Thank you," said Miggs. "And a nice way to treat a man of my age, I must say!"

"All in the game, Miggsy -- all in the game," said Mr. Tubbel. "And a good game it is, win or lose."

Miggs made no reply. He made his way out of the house and crossed the street, entering the house where Dan Fogarty still kept watch inside the door.

"Back, are you?" said Fogarty, and watched until Miggs disappeared around the turn of the stairway. Then Mr. Fogarty, opening the street door cautiously, went out of the house and disappeared. Miggs and Mr. Murchison were alone in the house, which was now unguarded and open to whoever chose to enter.

Hardly had Mr. Fogarty disappeared or Miggs reached the improvised study of Roger Murchison, when the doorbell jangled sharply and the noisy feet of a half-score men awakened the echoes of the lower hall. Together Miggs and Murchison peered down the stairway, to see the gray-haired Alonzo Herris, his trusty men and the veiled lady.

"Ah, there you are!" cried Alonzo Herris as he spied Mr. Murchison above him. "A pretty roundabout route they brought me."

Roger Murchison hurried down the stairs.

"Roundabout or otherwise," he said, holding out a hand to the veiled lady, "any route is good that brings my cousin safely to me. For this is Miss Wiltson, is it not?"

"Miss Who?" ejaculated Alonzo Herris. "Miss Wiltson? Tut-tut, Roger! This is Miss Lind!"

The veiled lady removed the veil and showed a face neither man had seen before. Certainly she was not Rosa Lind, and although Mr. Murchison did not know it, she was not May Wiltson.

"What do you mean?" Murchison demanded of Mr. Herris. "This is not Rosa Lind."

"And what do you mean?" asked the old lawyer. "This is not Miss Wiltson. And I know it is not, for I have seen Miss Wiltson in your own home every day for some days now."

Roger Murchison drew a deep breath and looked from the unveiled lady to Mr. Herris and back again.

"And Miss Wiltson was not abducted?" Murchison asked slowly.

"Miss Wiltson abducted?" said Herris with annoyance. "What nonsense! Of course not. You are the person that was abducted."

"And who are you?" Murchison asked the unveiled lady.

"I? A friend of Rosa's," said the stranger.

"I see!" said Roger Murchison. "Very clever and very well played. And you, I suppose," he said, turning to Alonzo Herris, "have paid some silly ransom for my release, while I was worrying over an abduction that never occurred. May I ask, my dear Herris, just how much my Graft Syndicate has won this time with your help?"

Alonzo Herris reddened.

"With my help?" he cried. "With my nothing. I paid for you, but I paid not a cent more than you commanded -- not a dollar more than I was forced by your orders. This is your signature, is it not?"

Murchison took the paper. It was addressed to the old lawyer, and read:

By all you hold sacred I implore you to save my life. Rosa Lind has me in her power, and I shall be murdered unless you appear at the address below at five o'clock today. Be there without fail, with five hundred thousand dollars ransom, or I am a dead man.

The signature was his, with the two small dots above the sixth letter of Murchison.

"My own letter cleverly washed, and with the new message cleverly written in," said Murchison. "I suppose," he added, "you needed this young army of men to carry the money?"

Again Mr. Herris colored.

"I took them for my own protection," he said angrily. "I had sense enough to know that if I was lost, all was lost,"

"And as it is," said Murchison cheerfully, "I have been buncoed out of only a trifling half-million dollars -- which, with the addition of the equal sum due Rosa Lind and my Graft Syndicate under their contract, makes a cool million."

"With the addition, if I may make so bold as to mention it, sir," said Miggs respectfully, "of the little matter of twenty-five thousand dollars you promised me."

"Quite so, Miggs, quite so!" said Roger Murchison.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 5:21:21am USA Central