from Everybody's Magazine

The Late John Wiggins

by Ellis Parker Butler

Yesterday morning, about ten minutes after eleven, John Wiggins passed away, and I hope he is now enjoying perfect rest. I hope his left leg is entirely etherealized. I trust, now that John Wiggins is thoroughly dead, he will stay dead. For a year I have not been able to write a line, and if I now break my long silence by this statement regarding the late John Wiggins, it is not that I wish to harm his memory; I owe it to myself to explain that I have not been silent through laziness.

I first met John Wiggins on the second day of May, one year ago. I was living in a small house in the village of Westcote, on Long Island, when I learned that the old Gibbs Mansion on Fremont Street was vacant. I leased the place and, on the first of May, moved in.

The house was large and stood in the middle of a fine lawn, studded with trees and shrubbery, and there was a good-sized stable in the rear; the whole place, however, was in bad trim. The grass had not been cut for months, and the shrubbery needed trimming, but I could see that the grounds could be made very beautiful with a little work, and the house was just what we wanted. One room would make an ideal study; my wife was enthusiastic over the many bedrooms; Mary, our servant, was happy in a large kitchen, and my father, who loves outdoor occupation, could hardly contain the joy with which the sight of the large and ill-kept gardens filled him.

"Now, Edgar," he said, as soon as we had taken the place, "I want you to let me make the yard my province. Let me attend to that." And he was so hurt when I proposed to hire a man, even by the day, to do the first rough work of putting the place in shape, that I agreed to let him have entire charge of the yard.

Toward evening we had things installed in a rough, temporary way, and next morning we all set to work hanging pictures and so on, and I was hard at it in the room I had chosen for my study, on the second floor, when Agnes called up to me.

"Edgar," she said, "can you come down for a minute? A man wants to see you."

I went down just as I was, collarless and bare-armed, and as I descended Agnes vanished toward the kitchen, merely saying, as she went: "In the parlor."

In the parlor, sitting on one of the chairs, was a rather stout man with a red face. He looked like a hearty and well-tanned market gardener dressed in his Sunday clothes, and, while he was neither impertinent nor bashful, his manner might be described as one of tremulous obstinacy, as if he had come to ask an ungrantable favor and meant to have it granted.

"Well," he said, with a sheepish grin, before I could speak, "I've come back." Immediately, as if he felt he had made a mistake, he said it again, differently.

"Well," he said, gruffly, "I've come back." There was something threatening in his tone, which I resented, and he tried again. He said cheerfully, "Well, I've came back."

"Back?" I said, puzzled.

"That's it," he said triumphantly. "I was afraid I couldn't do it, but I done it! I'm back."

I tried to remember him, but I could not.

"I'm John Wiggins," he said, as if that settled it, "and you needn't bother riggin' up a room for me in the house. I'll sleep in the barn. Don't you go to no trouble for me at all. I'll eat in the kitchen."

I was about to explain that he must have mistaken the house, when he went on. "Come to think of it," he said, grinning, "I don't eat."

I began to tell him that the people who had once lived in the house were now elsewhere, when he interrupted me. "Come to think of it," he said with a greater grin, " I don't sleep."

He bent over and rubbed his left knee and calf, ending by giving the ankle a few brisk nibs. When he straightened up, his face was red.

"I might say," he said, "that wages ain't no object. Ain't that fair? All I want is work, and no feed and no sleep. Ain't that fair? And no wages. Ain't that fair? And come to think of it, it don't make no difference, anyway. I've come back, and you can't help it. Where d'you keep the scythe?"

"Now, see here!" I said suddenly, for, although I am a good-tempered man, I felt that this fellow was going too far. "I don't know what you want, but I know I don't want you. Good morning."

John Wiggins rubbed his left leg, but he did not get up. "I just thought it would be sort of polite to let you know I was coming," he said, "and if you ain't got a scythe I can use a sickle, but if you ain't got a sickle you'll have to get one. That grass is too long to cut with a lawn mower. It wouldn't cut, it would mash down. And you'd better," he added, rubbing his knee -- his left one -- "get a pair of shears to trim the hedge with."

This did make me mad! Who was this man to foist himself upon me in this way? I had an impulse to throw him out, but he was such a large man that I restrained the impulse.

"See here," I exclaimed, "I have no time to fool away. If you have a sensible request to make, make it, and I'll give you a civil answer. Who are you, anyway?"

"Well, now," said the man, rubbing his leg gently, "I'll tell you. I'll tell you, but I wouldn't tell everybody, by no means. I'm a ghost."

He grinned, and continued rubbing his left leg. I could see nothing ghostly about him. To my normal eye he was a hearty man-of-all-work with, perhaps, a touch of rheumatism in one leg; and to my normal nose he offered the unspiritual odor of a stale tobacco pipe; my normal ear could hear him breathe. I never saw a man with fewer ghostly qualities.

"Nonsense!" I exclaimed.

"Well, now," said John Wiggins frankly, "I admit I didn't bring no written testimonials with me. Truth is, I couldn't git them to give me any. I asked for some, but they refused. You see, I've got a bad leg."

He stuck his left leg straight out and looked at it sadly. "That's the feller," he said reproachfully. "That's my bum leg. I can't git no testimonial until that leg's cured. That leg has got a bad case of inetherealization, it has, and that's why I've got to git a job here. I've got to stay here and work until that there left leg etherealizes proper. That's the prescription I got. Mebby you don't know Mr. Garland -- Mr. Hamlin Garland?"

"No, I don't," I said. I was now convinced that my visitor was merely insane -- perhaps a harmless lunatic.

"That's too bad," said John Wiggins. "Mebby if you did you'd know something about ghosts. And mebby you wouldn't. Did you ever hear of materialization?"

"Yes," I said.

"Well, there ain't nothin' to it," said my guest. "It works the other way about. Ghosts don't materialize. Folks etherealize. Take old Mrs. Gibbs I used to work for. She was a good old lady and done her duty, and she etherealized complete and proper when her time come, but I didn't. I had somethin' on my conscience, and it settled in my left leg and that leg ain't never etherealized to this day. It just stays a mortal leg, and you can figger how mean it is for an ethereal ghost to have a mortal leg on to him. Like as if a puff of steam had the old iron teakettle tied on to it. It makes it mighty unhandy for a ghost to git around, not to say impossible, him as light as gas and his left leg on to him like a lead sinker. So I begun to look up what was the matter, and I took advice on it. 'Well,' says doc, 'you must have done some crime.' But I hadn't, and I told him so. Come to find out, it was the way I treated poor old Mrs. Gibbs the last year she was alive. I hadn't have ought to have done it, and that's a fact, but I did do it. I soldiered on her. I skimped my work. I took advantage of her being so old and forgetful, and I only half done my work, and some things she told me to do I didn't do at all.

"So doc examined my left leg and he says there's only two things to do. One was to have the leg amputated and go around all the rest of forever as a one-legged ghost, and the other was to go back to the place I'd loafed and put in the time I'd loafed, and do the things I'd not done, and that would cure up my left leg. Doc said I'd only have to put in, each day, the time I'd loafed the similar day, and do up the odd jobs I'd left undone. So here I am."

"Mr. Wiggins," I said firmly, when he had finished, "I will not have you around this place! I do not care a whit whether your left leg etherealizes or not. But this I do know: my wife is deathly afraid of ghosts, and for that reason I do not want you around if you are a ghost; and my father is going to attend to the yard and would resent your presence, so I do not want you around if you are not a ghost. I do not believe in ghosts, but you may, if you choose. That is your right. But if I find you around here I shall treat you as a common and obnoxious human being and see that you are placed where you will do no harm, and that is in jail, for trespass."

I expected this to frighten John Wiggins away, but he only grinned.

"It's time for me to be gitting along," he said, "but I'll start in tomorrow, so if I was you I wouldn't worry about it."

I thought best to humor his delusion. I could arrange to have a policeman at the house the next day, and that would settle the matter.

"Very well," I said; "but let me ask you two favors. My wife is afraid of ghosts -- do not let her see you; and my father is jealous of his yard -- do not let him see you."

John Wiggins thought for a moment. "All right," he said at last, "that's fair enough, and I'll make a bargain. I'll keep out of their way if you'll store this here left leg of mine when I ain't working, and --"

Suddenly John Wiggins turned white and half rose from his chair. He stared at the door behind me, and I turned, but I could see nothing. I heard Mary McGuffy's voice calling some words out of the kitchen window to my father.

"All roight, sor," I heard her say, "Oi'll ask Misther Edgar."

John Wiggins gasped and licked his dry lips. "Gin -- gin -- ginger!" he managed to mutter. "It's Mary -- Mary McGuffy -- it's my old sweetheart! And she always was afraid of ghosts! I'm going to --"

I heard Mary's heavy tread in the hall, and, as I looked at him, John Wiggins rapidly turned into thin white air and vanished. There was a thud on one of my Turkish rugs, and I had just time, before Mary appeared, to drop on my knees and wrap John Wiggins's unetherealized left leg in the rug.

II

Few men, I imagine, have ever had occasion to wrap a leg in a rug, and those who have probably chose some other rug than a stiff Daghestan. Had I been choosing I should have chosen some other rug myself, but I was hurried. I had to act instantly. No man wants his servant to enter a room and see him standing idly before an unattached leg. It would be hard to account for such a piece of property in any event, and I foresaw that it would be most unpleasant for me to have to explain to a superstitious creature like Mary that what she saw was the leg of her recent sweetheart. I could not stand there and, with apparent indifference, say, "Mary, there is John Wiggins's leg. Take it away." So I sat down and rolled the leg in the rug. It made an awkward, bulky parcel, and, as it had a tendency to unroll, I took it in my arms and hugged it.

I think Mary was surprised to see me sitting on the parlor floor hugging a large rolled-up rug as if it were a doll, one end of the roll on my lap, and the other reclining on my shoulder; but I tried to appear as if this were necessary work in fixing up the house. Luckily, moving time is the one time when a dignified man can sit on a bare floor with legs extended and hug a rug without being considered insane, and I was puzzled that Mary showed any surprise at all, until I discovered that John Wiggins's boot was protruding from the end of the roll that lay against my cheek. I admit that Mary was right to be surprised. Logically, she could not understand why, when there was so much work to be done, I should wrap a boot in an Oriental rug and sit down on the parlor floor and nurse it.

When Mary went, I jumped up nimbly and started upstairs with the rug. I had no time to lose. If Agnes came upon me she would not stare and go away like Mary. She would want to know why I was taking the rug out of the parlor, and what was rolled in it. So I dashed upstairs and into my own room and shut the door. My first thought was my closet, but I knew that at moving time no closet is sacred. I realized that no place in the house would be a safe hiding-place for John Wiggins's left leg; anything may be in any place at moving time, and every one may look anywhere. The can opener is likely to be in the jewel cabinet, and the desiccated codfish in the chiffonier.

But I solved the matter. Our window curtains were not to be put up until fall, and I wrapped John Wiggins's leg in manila wrapping paper and tied the parcel with stout twine. On the paper I wrote, in ink, "Curtain Rods and Fixtures," and stood the package boldly in the corner of my room. It was safe there. Agnes looked at the package once during the day, but when she read the words I had written she turned away.

The next morning I was awakened by a knock on my bedroom door, and when I opened it I found my father, in his bathrobe, looking displeased.

"Edgar," he said, "there is a man in the back yard cutting the grass. Of course, if you want a man to cut the grass, I have nothing to say, but I thought it was understood that the grounds were to be my work. And if it is, as I suppose, some one stealing the grass for his horse, he shouldn't be allowed to do it."

I threw on my bathrobe and went into his room, where a window commanded the back yard. Instantly I knew John Wiggins had come back. Even at that distance I could recognize the wrapper I had put around his left leg, and I thought I could make out the words "Curtain Rods and Fixtures."

"Father," I said with pretended anger, "I will soon see what that man is about! I never heard of such impudence!" I hurried out to where John Wiggins was strenuously swinging a scythe.

"Hello," he said pleasantly, when he saw me. "You see I have came back, like I said I would. Much obliged for keeping my leg, but it ain't really necessary to take so much trouble with it. You don't need to mind to wrap it up; it won't hurt none to git a little dusty. I'd of took the wrappers off, but I ain't got much time to make up today, and I didn't want to waste none. You see they've got my schedule all laid out, day for day, all the days I loafed any, and all I have to make up in any one day is what time I loafed on the correspondin' day when -- when I was here before."

I glanced up and saw my father looking at us from his window, and I began to speak to John Wiggins in a violent manner. He paid no attention.

"I see you didn't git no sickle, like I told you to," he said reproachfully. "I had to go over next door and sort of borry this scythe without sayin' nothin' to nobody about it. I guess you'd better git --"

At that instant John Wiggins faded gently away and left me standing before his fallen scythe and his left leg. He had made up his time for that day. I looked guiltily toward the window; my father was gone. I gathered up the leg and hurried into the house with it, and managed to hide it in the low closet in the butler's pantry before my father came down.

"I settled that pretty quick!" I said. "I sent him about his business. If you see him about here again, let me know. And I wish, after breakfast, you would take that scythe home. The fellow took it, without permission, from the house next door. Explain it." I thought I had better let my father do the explaining, because I was afraid I might explain a little too much if I tried it myself. My nerves were upset.

That day I did little work. It required diplomacy to get that leg out of the butler's pantry. I assumed an air of unconcern and rummaged in the closet; pretended to find the parcel marked "Curtain Rods and Fixtures" unexpectedly, and carried it to my room. I put it in the darkest corner of my closet and shut the door, and sat down to think the matter over calmly if I could. My first impulse was to take my family and leave this house entirely; my second thought was that I could not take, this year, even my usual family vacation in the mountains. I did not dare go away and leave John Wiggins to drop his leg about the place promiscuously. I trembled as I imagined the scandal that would follow the finding of John Wiggins's left leg -- the huge headlines in the newspapers -- "Noted Author Suspected," and so on, and the pain the notoriety would cause Agnes. Clearly, my fate was to remain at home and follow John Wiggins, ready at any moment to gather up his leg. I spent a miserable day. One moment I rushed hurriedly to buy a sickle, and the next I started resolutely to destroy John Wiggins's leg. I bought the sickle, but I did not destroy the leg -- I did not dare.

Early the next morning I was up and dressed, ready to go down the moment John Wiggins appeared. But he did not appear! All that day his leg lay dormant in my closet. When, the next morning, he still did not come back, I could hardly contain myself. I shut myself in my study and paced the floor, and I was near a nervous breakdown when my closet door opened and John Wiggins stepped out. It was ten minutes to twelve.

He stood before me and smiled. "Well, how're you feelin' today?" he asked. "I've got a little job to do in this room, an' if you'll tell me where I can find a hammer and a big nail I won't trouble you to git them. I've got to put a nail into the wall right up there where that picture is."

"You will not!" I declared. "I have just had this room papered, and I will not have any nails --"

"Sorry," he said, "but I've got to put a nail in. Old Mrs. Gibbs she told me to one day, and I didn't do it, and now I've got to."

I got the nails and the hammer for him, and he stood on a chair and removed the picture. He handed it to me, and I stood holding it as he drove the big nail just where I did not want any nail to be. I saw the plaster crack as the nail went in, and I knew it would make a bad hole when I pulled the nail out again. I asked if I had the right to remove it when he'd finished.

"Why, cert'," he said good-naturedly. "All I've got to do is what I left undone when --"

At the last blow of the hammer John Wiggins vanished and his left leg toppled off the chair. I caught it just in time to receive the falling hammer on the back of my head. A couple of nails John Wiggins had been holding clattered to the floor, but I did not hear them, for the hammer had stunned me. When I regained consciousness I was lying on my bed, and Agnes was bending over me.

"Edgar," she exclaimed, "what were you trying to do? Why did you drive that nail into the new wallpaper? What were you doing with that bundle of curtain rods?"

"The curtain rods!" I cried wildly. "What did you do with the curtain rods?"

"Now lie down," she urged, pushing me back. "Don't worry about those old curtain rods. I had Mary put them in the closet of her room, out of the way until next fall."

That instant a wild scream came from the floor above, followed by the thud of a heavy body bouncing from step to step, and a crash as the door at the foot of the servants' stairs burst open. From my bed I could see Mary on the floor at the bottom of the stairs, rubbing the back of her head. Her face was white, and her eyes were staring, and she was breathing hard. Instinct told me that John Wiggins had come back to do some little odd job in the garret, and had met Mary; and I had no heart to scold her for coming downstairs so carelessly. Any girl would be surprised if, on opening a closet door, her late deceased lover should step out, with one leg done up in manila paper.

Agnes had rushed to Mary, but when Mary was able to speak she shut her lips tightly. I saw there was no danger of her saying anything about John Wiggins. She was superstitious, but she had a natural dread of ridicule. As soon as Agnes was sure Mary had broken no bones, she went downstairs, and I heard Mary go up to her room. In a few moments I saw her come down again with the bundle labeled "Curtain Rods and Fixtures." I was not surprised to see her carry it into the bathroom and throw it out of the window into the middle of a large lilac bush. Ordinarily I should have spoken to Mary in no mild tone about treating a bundle of curtain rods and fixtures in that way, but I said nothing.

I dressed hurriedly and hastened downstairs, but I was too late. My father had already rescued the package from the depths of the lilac bush, and as I peered cautiously from the back-parlor window I saw him carrying it toward the barn. He had it tucked under his arm, and he was half-way across the yard when John Wiggins appeared suddenly on the end of his left leg. He was in an awkward and uncomfortable position, and as he stood facing my father he had to hop up and down on his right leg to maintain his balance. He might have had a bad fall had my father not instantly released his hold on John Wiggins's left leg. But he did release it instantly. No one could have released anything more quickly in any circumstances.

John Wiggins immediately began talking to my father in his usual good-natured way, but I could see that my father had no desire for conversation. He seemed distraught, and, after standing a few minutes in absolute silence, he walked to the house, went to his room, and locked his door. For months my father remained in a dazed condition. He never said anything to me or to Agnes about it, but I could see that he was worried. He used to linger near John Wiggins, and when he disappeared my father would sigh and pick up the left leg and carry it meekly to the barn. If John Wiggins had been a child, and his left leg had been his toys, and my father had been a nursemaid, my father could not have gathered up after John Wiggins more faithfully and patiently than he did. He never uttered a word of reproach, although John Wiggins was most disorderly in the way in which he would go off and leave his leg here and there.

Of course, this attention on the part of my father relieved me of the necessity of giving all my time to the ghost of Mrs. Gibbs's late hired man, but it did not relieve me from the worry. Nor from the expense. I was careful not to let my father or Mary know that I knew anything about John Wiggins, for I saw that each considered him a personal hallucination, and I also saw that they concealed from each other their common imaginary weakness. I saw Mary and father watching John Wiggins at work -- the one wide-eyed and breathing hard, and the other depressed and worried -- but neither gave any sign to the other of realizing the presence of John Wiggins. My father would hear John Wiggins ask Mary for a hammer or a drink of water, but he would make no sign. He pretended not to hear. And Mary would watch my father gather up the leg and carry it away without a word. She pretended that she did not see it; and sometimes, when John Wiggins etherealized in the kitchen, Mary would carry the left leg to my father and give it to him, but she never admitted that it was John Wiggins's left leg -- she always said, "Here's them currtin rods."

What worried me most was the fear that Agnes might see John Wiggins and understand what he was. I dreaded the effect on her tender nerves should she see John Wiggins suddenly appear on the end of the bundle of curtain rods, or should she see him as suddenly melt into thin air. It seemed a miracle that she did not suspect something, for John Wiggins came and went continually, and she must have seen him at work. I could not understand how she could see a man cutting our grass, with one leg done up in manila paper, and not think it odd. But she said nothing until she expressed a mild surprise that I had bought a horse.

I was sitting in my study one morning, in a most depressed condition, when I heard John Wiggins enter. He was smiling good-naturedly, as always.

"Well, now," he said, "the fact is you've got to git a horse by tomorrer mornin'. There's some work I've got to make up in the horse line, and you've got to buy a horse."

"John Wiggins," I said with exasperation, "I will not buy a horse."

"Cert' you will," said John Wiggins pleasantly. "And I'll tell you the horse you've got to git. The horse I didn't do my duty by was the horse old Mrs. Gibbs had, and that horse's name is Tom, and that's the horse I've got to work on. I neglected that horse shameful. You can git him from my brother Ike. I've spoke to Ike about it."

There was nothing for me to do but buy the horse -- and of all outrages! Ike had been spoken to, evidently. He asked two hundred and fifty dollars, and he wouldn't come down one cent. He said nothing about John Wiggins, but he smiled in a way that meant a great deal. "Take him or leave him; two fifty is the price," was all he would say, and I had to take that horse at that price. Mrs. Gibbs had been dead a year, and I should say that she had had Tom twenty years, and that Tom had been fifteen years old when Mrs. Gibbs bought him. That makes thirty-six years, but Tom looked older than that. There was plenty of work to do on Tom, and the work was increased because he had to be held upright with one hand while he was being curried with the other. Many times John Wiggins etherealized while he was currying Tom. I would hear a thud in the barn and know that the sudden removal of John Wiggins's retaining hand had let Tom fall to the floor, and that in the barn my poor, patient father was prying Tom off of John Wiggins's left leg. It made a great deal more work for my father.

I was unable to explain to Agnes why I had bought that horse, but it was a logical purchase as compared with the buggy. John Wiggins's brother Ike insisted that the buggy was cheap at one hundred and fifty dollars. I bought the buggy because John Wiggins had not washed it as often as he should have washed it, and as a washing buggy it satisfied John Wiggins. He washed it long and often, but Agnes expressed surprise that I should have bought the desultory remains of a buggy merely to have them washed. She said it seemed foolish to her to have the buggy drawn out in front of the barn every morning and washed and then put back until it was time to wash it again. She said she would ask me why I did not have the horse hitched to the buggy, and take a drive once in a while, except that any one could see that they were not the hitching or driving kind.

My nervousness increased daily. I could not write in that state of mind, and yet it seemed absolutely necessary for me to write in order to keep up an income, for John Wiggins and his brother Ike were ruining me. It is an inestimable advantage for a dealer in odds and ends to have a ghostly brother. I found that Ike Wiggins had bought nearly everything that Mrs. Gibbs had owned that John Wiggins had neglected, and all these I was obliged to repurchase. I hated to have to pay eighty dollars for an old heating furnace when my house was nicely fixed with a hot-water apparatus, but I had to do it so John Wiggins could spend a day cleaning the pipes, and this was followed by the purchase of a flag pole to paint, seventy-eight old boards that had once been a floor and that needed varnishing, a thousand old bricks that had to be carried from one side of the yard to the other and piled, and even a dead rosebush that had to be watered; but when John Wiggins, one cold day, made me go down to his brother Ike's and buy a pile of gravel that had once been a walk in the back yard, so he could shovel the snow off it, I really thought he was imposing on me, for brother Ike made me pay seventy-five dollars for it.

I thus gradually accumulated nearly everything that had once been the stock in trade of Ike Wiggins, but day before yesterday, when I went to his place to buy several yards of old picket fence for John Wiggins to nail loose pickets to, I saw Ike looking doubtfully at a wrecked automobile in his scrap yard. I went home in the depths of depression and threw myself on the bed to weep. I was totally unstrung, and my bank account was worse than that. I could not have bought even a new automobile, and I knew that an old one that had belonged to Mrs. Gibbs was far beyond my means.

When I heard Agnes enter the front door, I arose and tried to hide the traces of my weak tears. I heard her firm tread on the stairs, and she entered the room and closed the door behind her. I saw firmness and resolution in every line of her usually gentle face.

"Edgar," she said severely, "I have a confession to make. For over a year this house has been haunted, and I knew it all the while! And I knew that you knew it. Oh," she said quickly, as I opened my mouth to speak, "I know I've done wrong, but I did not know it at the time. I saw that you were laboring with the trouble, and I did not like to worry you additionally by letting you know I was worried, too. But the last month you have been growing more and more depressed, and I felt it my duty to do what a woman could do."

"Agnes," I cried, "what could you do?"

"I watched," she said. "I felt that the future of us all depended on me, and that made me brave. I saw how your poor father was gathering up John Wiggins's leg day after day so meekly and uncomplainingly; how Mary was doing her work in spite of the care she had on her mind, and how your bank account was dwindling to nothing to supply John Wiggins --"

"You know his name?" I exclaimed.

"Indeed yes," she said. "You talk in your sleep, Edgar. But I know more than that. I know that John Wiggins never worked for Mrs. Gibbs."

"He was a lazy fellow," I admitted.

"He never worked for her at all," said Agnes, and while I stared at her she continued, "Do you know where his left leg is?"

I thought I did. I said my father kept it on a shelf in the barn. Agnes, in two words, ordered me to get it. I hurried to the barn and brought back the manila package to her. With a few quick snips of the scissors she opened the package. There was nothing in it but an old shoe and some rolls of rags.

"There!" she exclaimed. "And the same was in the package at Mr. Gray's and at Mr. Overman's and at Mr. Gerster's. At Mr. Long's there is the same. John Wiggins has been at Mr. Long's only a week. Mr. Gerster has just bought a horse of Ike Wiggins. Mr. Overman has just bought a buggy. Mr. Gray has just bought a flagpole from Ike Wiggins. All of them live in houses where recent occupants have died."

"Agnes!" I exclaimed.

"All of them!" she repeated. "And to all of them John Wiggins has told the same story. He is the most disreputable, mean, dishonest ghost I ever heard of. He has robbed all of us to benefit that worthless brother of his, and if I hadn't disliked the look of his eye he would still be robbing us. Luckily, I went down to see what sort of man Ike Wiggins was, and there I saw Mr. Gray, looking just as worried and sick as you do, and I guessed the rest. I saw Mr. Overman and Mr. Gerster and Mr. Long all come to the same place, and I went to see their wives."

When she had said this she paused, and for some time I thought deeply. "Agnes," I said at length, "I have never had much faith in ghosts --"

"And I shall never believe in one again," she said.

"That is right," I said; "they do not deserve to be believed in. But now that we know the true character of John Wiggins's ghost, how are we to get rid of him? You are sure you do not believe in ghosts?"

"Not now. I did once, Edgar, but since I have met John Wiggins's ghost I do not. He is beyond belief."

"He is," I said. "If I let myself be fooled into believing in him, it was only because he had such good proof. He left a leg with me. But now I have no leg of a ghost, I do not believe in ghosts. Ghosts exist for their believers only. And I am sure my father has seen too much of John Wiggins to believe in him. The only doubtful person is Mary."

"If Mary believes in ghosts she must go!" said Agnes firmly. "We cannot have a ghost hanging around the house just because a servant believes in one."

I went down to interview Mary, and, though I would have been loath to lose such a good maid, I was fully decided to discharge her at once if she believed in John Wiggins. But I found she did not. She admitted that she had at first, but lately she had fallen in love with the fishman, and she assured me that since then she had entirely disbelieved in John Wiggins. This made my task easier, and I prepared to receive John Wiggins as he deserved to be received.

He came next morning about eleven o'clock -- yesterday morning -- and I met him in the yard. He was as self-possessed as ever, and as smiling, and he wore the manila paper wrapper just as he had always worn it, for I had been careful to put it in its usual place in the barn.

"Well," he said heartily, "I guess you'll have to git an automobile, I guess you will. I never tended to Mrs. Gibbs's automobile the way I ought to have, and brother Ike has it. I guess you can buy it from --"

"Stop!" I said imperiously. "This has gone too far. You can fool me a while, but not forever. I no longer believe in ghosts. You have long ago worked your leg out of inetherealization. Get out of here!"

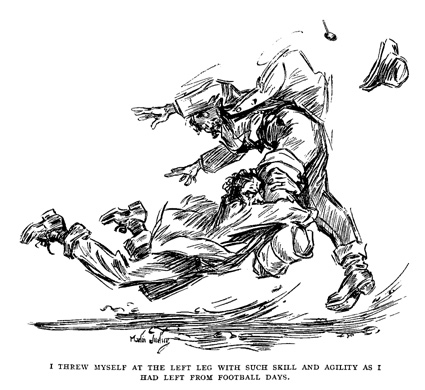

For answer he only grinned, and rubbed his manila package where it was marked "Curtain Rods and Fixtures." Had I entertained any doubts -- had I imagined there was a real leg in the package, I must even then have suffered defeat, but I myself had filled the package with gunpowder. I threw myself at the left leg with such skill and agility as I had left from my old football tackle days, and wrenched the leg from John Wiggins. As I had expected, another leg stood in its place, but even as John Wiggins grappled with me I made a backward pass of the package and tossed it to my father, who struck a match and touched it to the paper. Instantly there was a flash, and all the proof we had that there was such a ghost as John Wiggins disappeared in a cloud of blue smoke and faded away; but not before Agnes had caught a snapshot of it, showing that both legs were now etherealized.