| ||

| ||

from Century Magazine

The Ethiopian Dip

by Ellis Parker ButlerJudge Anthony Deakin stepped from his low-power, inexpensive automobile at the gate of the grounds of the Third Annual Amateur Carnival and Circus for the Benefit of the Riverbank Free Hospital, and turned to Mike, his man of all work.

"Mike," he said, "just you turn the car around and stay in it. You keep the motor going, you understand? Maybe this is going to be all right, but if I come out on the run, you speed up the minute I get aboard. Got plenty of gas in the tank?"

"She's full," said Mike. "Suppose I have the car over yonder under that lamppost?"

"No you don't!" said the judge. "I'm not going to run unless I have to; but if I do, I want to get a quick start."

The judge was an honest man. When he sat on the bench, to which he had been elected on the non-partisan ticket, he saw neither lawyer nor client, friend nor foe. Once he had had friends, but of late they had suddenly diminished in number until only his old cronies would admit their friendship. He was, as he entered the carnival grounds, the most hated and objurgated man in Riverbank. Again and again, in deciding a suit, he had "thrown" his friends, as they called it, and had given a decision favoring a political enemy or a stranger; but in the case of the R. & N. bonds he had had a chance to make every citizen of Riverbank his enthusiastic admirer, and he had deliberately made them his bitter enemies. The time when he would be renominated or dropped was at hand.

The R. & N. bond case had been a sore matter with Riverbank for years. In the enthusiasm of the old railroad boom days, Riverbank had voted fifty thousand dollars in city bonds to aid the Riverbank & Northern Railway, and had sold the entire lot of bonds to some creature in New York. At the moment the creature was considered a benefactor. The interest on the bonds had been cheerfully paid for a few years, then reluctantly paid, and now the bonds were due. Some of the wise men about town had decided that the bonds had been born in iniquity, that the railroad would have been built anyway, that it was a criminal waste of money, and that the bonds were illegal and ought to be repudiated.

On this platform they got themselves elected city officials. They refused to pay the interest when it next fell due, on the theory that the bonds were worth no more than waste paper, and the creature in New York, or his heirs, brought suit against the city.

It would have been the easiest matter in the world for Judge Deakin to have decided in favor of the city. It was a certainty that, whichever side won in his court, the case would be carried to a higher court. What Judge Deakin decided was apt to be rather immaterial in the final outcome of the case. But he promptly decided for the creature in New York; and he added insult to injury by stating from the bench that in all his life and in all his long study of such cases he had never seen or heard of such an unwarranted and wicked attempt to defraud an innocent purchaser out of his property.

Judge Deakin became immediately the most unpopular man in Riverbank; yet, in the face of all this, he was entering the carnival grounds. It was characteristic that, because the carnival was being given for a worthy cause, Judge Deakin meant to be present and spend as much money as he could afford.

At the gate he handed the ticket-seller a dime. For an instant the ticket-seller hesitated; but he realized he had no authority to refuse any one admission, and he reluctantly pushed a ticket toward the judge, who took it and went in.

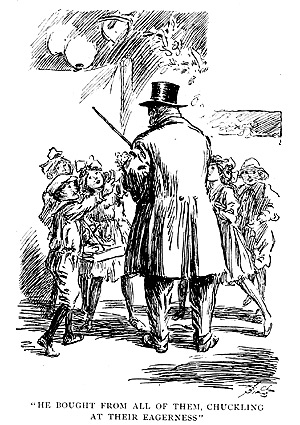

Just inside the gate a dozen children, boys and girls, crowded about the judge, offering popcorn and peanuts from their gaily decorated baskets; and the judge laughed at the manner in which they mobbed him, pleading, "Oh, Mister, buy one from me!" and "Oh, Mister, buy some peanuts from me, won't you?" He bought from all of them, chuckling at their eagerness, and then handed his purchases back. He seldom smiled except at children.

"Look at the old reprobate trying to square himself," said one of the carnival managers, seeing the transaction. "I wish we had some way to keep him out of the grounds."

"Good evening," said the judge to the manager, but the manager turned away without replying. The judge walked on stolidly. He carried a cane, as always, but this evening he had chosen his lightest and thinnest. A heavier cane might have been construed as a protection.

The grounds were brilliantly lighted and decorated, and half the women of Riverbank seemed crowded in the various booths, tempting the crowd to buy. Two hands and a drum-corps added to the musical din of which the hurdy-gurdy on the merry-go-round had been for three days the prime leader. Half a hundred amateur "barkers," with long megaphones, shouted at the crowds, and every one was buying and throwing confetti, laughing, and chaffing one another good naturedly.

In this one booth the committee in charge sat dolefully. The last night and the big night of the carnival had come, and this booth was not taking in a penny. In the final report, to be published in the "Riverbank Eagle," with the individual results of each booth, "Income, Expense, Net Result," the booth of the Fourth Ward Republican Club seemed doomed to show a loss, and to be the only booth so unfortunate.

Mr. Almon, the chairman of the committee from the Fourth Ward Republican Club, sat on a camp chair and smoked his pipe sadly.

"Well this is going to be a hard knock for us, boys," he said. "They'll rub this into us good and hard. Look at them Democrats over there, with that Hit the Coon booth. They're taking in money by the fistful."

"They've got to make allowances for us," said Mr. Briggs. "We tried, didn't we?"

"Oh, now, there's no use trying to make ourselves think anybody is going to make any allowances for us, either," said Almon. "They'll say, 'That Republican crowd are dead ones.' That's what they'll say. Look at that crowd around the Knock the Babies! And who is running that? The Morning Star Literary Society of South Riverbank. Say, the Morning Star Literary Society! And look at us! What have we took in? Three dollars and fifteen cents. How will that look? 'Second Ward Democratic Club, Hit the Coon, two hundred dollars profit. Morning Star Literary Society, Knock the Babies, one hundred and fifty dollars profit. Fourth Ward Republican Club, that thinks it is the livest little political bunch in town, Ethiopian Dip, forty-seven dollars loss.' And after they gave us our choice, and we picked out the best proposition, and the only new one! Gee! I feel like leaving town and never showing myself here again."

"Well, how could we help --"

"Yah!" said Mr. Almon, disgustedly. "Wait until you hear those Democrats say, 'Yes, we made two hundred dollars; but if we had had that Ethiopian Dip, we'd have made four hundred.'"

"That's all right. But even a Democrat can't make a Riverbank Negro like water, can he?"

"They run this dip other places," said Mr. Almon.

"Now, don't be trying to say it was my fault," said Mr. Briggs. "I hired the Negroes, didn't I? I did all I could."

"I'm not saying it was your fault," said Mr. Almon. "I only say we'll look nice, we will, in the papers. That's all."

"All right. What are you going to do about it?" asked Mr. Pierson.

"Do? What can I do? We can't do anything. Gimme a match."

The Ethiopian Dip was a canvas tub slung between four posts and filled with water. Over the tub was a suspended seat on which the Negro sat, as in a swing. In front of the Negro was a net protecting him from the baseballs, but protruding through the net was a small target, and when a ball hit the target, a catch slipped, the seat parted, and the Negro dropped into the canvas tub with a loud splash. Whoever dipped the Ethiopian received one of the worst cigars that ever left the Nutmeg State; but the cigar was a minor reward. The joy was in the splash.

Mr. Briggs, having been delegated by the committee of the Fourth Ward Republican Club to hire a supply of Negroes to be dipped, had done his work well. He had hired three, and he had provided bathing suits for them, and he had seen them arrive behind the booth the first afternoon of the carnival. It had been no easy task. There were few Negroes in Riverbank, and the Democrats had hired most of them to relay in the Hit the Coon. The remaining supply numbered exactly three, and Mr. Briggs's verbal description of the Ethiopian Dip aroused no enthusiasm in the three. Mr. Briggs, having had only a verbal description from a manager who had never seen the Ethiopian Dip, but had only heard of it, was rather vague. To sit on something like a trapeze and have the general public throw balls at one until knocked off the trapeze into a tub of water hardly impressed a non-bathing gentleman as a desirable job.

But Mr. Briggs used all the persuasiveness of his tongue and the money he was authorized to offer, and he prevailed. At noon of the first day he went to the carnival grounds to look things over, and remembered that the canvas tub must be filled with water. He paid two small boys a quarter each to fill the tub, and went to his dinner, content that he had done everything necessary. He did not know that the ice cream booth adjoining had used the canvas tub as a temporary receptacle for ice, and that the small boys would pour upon the ice the water they were paid to carry. When the grounds opened to the public at two o'clock, the water in the canvas tub was cooler than even the most ardent devotee of cold baths would wish. The Arctic Ocean is no colder than that water was. No Gulf Stream emptied its warm waters into the canvas tub. It was pure, unheated ice water.

The three Negroes were very comfortable in their bathing suits in the shade behind the ice cream booth, for the day was hot. When Mr. Almon and Mr. Briggs arrived, they had already shaken their crap dice to see which of the three should take the first turn, and Silas had lost. He was a tall, loose-jointed Negro with a face normally expressing fear, and he climbed to the seat over the canvas tub with the expression of one going to execution.

"Now, then," said Mr. Almon, "we will just try it to see that everything is working all right. Come on, Briggs."

They went outside the counter and picked up two handfuls of baseballs. Silas gripped the sides of the seat with a death-grip.

"Here," said Mr. Almon, "you must not do that! Fold your arms. We don't want you to hang up there by the hands if we hit the target. We want you to drop. That's it. Keep 'em folded."

He threw a ball. It missed the target by about a foot and a half, and went straight toward Silas's face. The net intervened, but instinct made Silas dodge. He swayed, toppled, grasped for the seat too late, and, instead of falling with his feet outspread, in a sitting position, turned over and dropped into the tub headfirst. His legs kicked wildly in the air, his hands splashed in the water, and when his head came above the surface he uttered one long, wild, terrorized yell, threw his leg over the edge of the canvas tub, and, the instant he touched the earth, darted off in the direction of Derlingport, thirty miles away. Only once did he glance back, and then he saw his two companions running after him at the same speed. He thought they were trying to catch him. They were not. They, too, were running away.

After that short, but exciting, moment the Ethiopian Dip discontinued operations. There were no more available Ethiopians. When the managers came to see why the dip was not gathering in bags of money, and reproached Mr. Almon, Mr. Almon said:

"All right; get us the Ethiopians. That's all I've got to say. Get us the Ethiopians, and we'll dip 'em."

The manager hastened away, sure that he could get more Ethiopians; but after a few hurried attempts he gave it up. He kept far from the Ethiopian Dip after that.

Mr. Almon, looking across the grounds, saw Judge Deakin enter. He saw a pretty girl lean across the counter of a candy booth, smiling enticingly at the judge as she offered him a box of candy, and then he saw the lady chairman of the booth drag the girl back by the arm. As surely as if he had heard the words he knew what the lady chairman was saying. She was saying:

"Isabel, stop! Don't you know who that is?"

"No. Who?"

"That's Judge Deakin."

At the next booth the judge raised his hat, but the lady chairman and her three committee-ladies turned their backs.

"Look over there," said Mr. Almon. "There's old Judge Deakin come to the carnival. He has the nerve! If this was like any other town, he'd keep away from a crowd. They'd tar and feather him."

"It ought to be done to him, anyway," said Mr. Briggs.

"I'd like to give him the first coat of tar," agreed Mr. Almon. "By Joe! I wish I could! I wish I had that canvas tub there full of tar, and him on the seat up there, and I had half a dozen good, big croquet-balls to slam at that target. I'd tar him! And once I dropped him in the tub, I'd ram his head under."

"Don't blame you," said Mr. Briggs. "I'd feel the same if he'd acted the way he has after I'd pushed him for his job. It has hurt your prestige a lot, Almon, having him act that way after you got him nominated."

"Hurt it?" said Mr. Almon. "Killed it, you mean. All I'll have to do now will be to mention a man's name and he'll be knifed at the convention. 'What are you handing us?' they'll say. 'Another Judge Deakin?'"

"That's right," said Mr. Briggs. Mr. Almon looked across at the judge.

"Yes," he said, "and that ain't all the reason I have for not loving him. You know what he did to Tom Rollins."

"Gave him seven years in the pen?"

"You bet. And after I had spoken to the judge on the quiet that I wanted Tom let off. After I had proposed Deakin, and got him nominated, and worked my head off to get him elected, and then asked just one favor, -- to let Tom off free, -- he goes and sends him to the pen for seven years. And just because Tom got free with the back door lock of somebody's house! He didn't steal anything worth much, anyway. Say!"

"What?"

"Why, that old ingrate of a judge is responsible for this booth being a fizzle. Do you know that?"

"How do you mean?"

"Why, if he had let that Tom Rollins darky off, don't you think I'd have been able to make Tom let us dip him? Of course I would. He'd have had to do anything I said. I ought to love Judge Deakin, oughtn't I?"

The judge moved out of sight behind the flower pagoda. He still held his head erect on his bull-neck, but his little eyes seemed closer together than ever. He was not angry. He knew human nature well. He had expected to be unpopular after his bond-case decision, but it hurt him. He did not meet a friendly face except those of the little children who were peddling, and he even stopped buying from them, lest it be thought that he was taking a mean advantage of their ignorance. As he passed the flower pagoda, Mrs. Binton pointed him out to her helpers and laughed scornfully.

Mrs. Binton and the judge had been old friends. They had been friends when they were children, and there had been a time when they were engaged to be married. Mrs. Binton had, instead, become Mrs. Binton, principally because Harry Binton had six good horses and stylish rigs. She drove admirably and loved horses. For years she had taken the Ladies' Driving Event at the Riverbank Fair. Those who did not know her well were apt to call her "that sporty Mrs. Binton," but the truth was that she was merely full of life and "go," and unconventional enough to enjoy the things she liked best. Harry was always with her when she was doing the things that seemed unconventional. It was always Harry who led her to the shooting gallery at the carnival, and Harry who paid for the balls she threw at the Negro in the Hit the Coon booth, and Harry in his pink coat who rode at her side in the circus parade the first night of the carnival.

Mrs. Binton's friendship for the judge had ended when the judge decided the Merriwell will case against Harry, dissolving a charming vision of an automobile that had floated before Mrs. Binton's eyes. The Merriwell money had gone to the Merriwells, who did not need it, and Mrs. Binton felt that Judge Deakin had been unfaithful to a long friendship, and her friendship changed to bitter hatred. She had written him a letter that contained all the bitterness she could put in it. The judge had never replied.

The judge turned red when Mrs. Binton pointed him out and laughed. He was about to move on, but he turned back and leaned on the counter.

"I got your letter, Sally," he said. "I didn't answer it."

"I know you didn't," said Mrs. Binton. "There wasn't any answer you could make. And it is too late now to try to make any."

"I don't mean to make any. I only want to tell you I received it. It was impolite not to acknowledge it."

"Exceedingly," said Mrs. Binton. "But will you please move on? I don't want my booth to be unpopular."

Harry Binton, who had been chaffing with two girls over the far counter of the pagoda, came and stood beside his wife.

"I want to buy some flowers," said the judge.

"You can't buy any here," said Mrs. Binton. "If we thought we had any of your money, we would throw it out."

The judge rested one arm on the counter. He looked full in the eyes of Mrs. Binton.

"Sally," he said, holding her eyes with his, "I thought you were a good sport."

Mrs. Binton blushed. It would be more exact, perhaps, to say she flushed. He had attacked her where she held her pride the highest. She was a good sport, and she knew it; but she knew, too, that she had failed in so far as she had allowed herself to bear this grudge against Judge Deakin.

"Of these," said the judge, waving his hand toward the thousands of merrymakers that crowded the grounds, "I don't expect it. But I did think you were a good sport, Sally."

Harry looked at his wife. If she had made the sign, he would have leaped the counter and probably have been unmercifully thrashed in an attempt to thrash the judge; but she put her hand on his arm.

"This is my affair, Harry," she said. "Let me play my own hand."

"I always thought you were the finest sport I had ever known," said the judge. "I thought you were a thoroughbred. But I am a better sport than you are. I can take what is coming to me, just or unjust. I came here tonight. I knew I did not have a friend in the place. I expected to be insulted."

"If you had not --" Mrs. Binton began, but the judge silenced her.

"I expected to be insulted by all the people except the true sports," he said. "But I did think there were still a few who could play the game without getting cold feet. I was wrong."

"Oh!" exclaimed Mrs. Binton.

"Sally," said the judge, "I don't mean that. I'll take that back. But if you have a grudge, take it out of me in the open. Why, you -- you're acting like a woman! If you want to beat me up, beat me up, but be fair about it. If you want to duck me, duck me until I gasp, but shake hands afterward. Now will you sell me a flower?"

She took a rosebud from a vase and pinned it on his coat. He laid a five dollar bill on the counter, and she was sport enough to accept it and drop it in the cashbox. The judge lifted his hat and walked on.

"He had you there," said Harry Binton, and Mrs. Binton nodded.

The judge moved on around the line of booths with the rosebud in his buttonhole. At a few booths, where he was not known, he was greeted eagerly, and he made up for the reluctance to take his money at the booths where he was known by spending freely. When he reached the Ethiopian Dip he paused and spoke to Mr. Almon.

"Quit business?" he asked.

Mr. Almon scowled.

"Oh, move on and don't let folks see you talking to me!" he said. "You've done enough harm around here."

"Almon," said the judge, "I'm sorry if I've made myself unpopular. I had to do what I thought was right. In a year --"

"You've put me out of politics for a hundred years," said Mr. Almon, bitterly. "And you've put the finishing touch on the good work right here. If it hadn't been for you, this booth would be coining money; but just because it looked good for a Republican club to push an honest Democrat for the non-partisan judicial ticket, and I proposed you, my club and I are going to be laughed out of town. Look at those Democrats coining money for the hospital, and look at us!"

The judge was absolutely astonished. He had expected to be blamed for much, but that the failure of any booth in the carnival should be laid at his door was a surprise.

"Explain," he said shortly, and Mr. Almon explained. He dwelt on the willingness of Tom Rollins to do the bidding of the managers of the Republican Club.

"And if you were half a sport," he ended, "you'd get up there and take Tom Rollins's place, that's what you'd do!"

The judge bent down. Mr. Almon dodged, thinking the judge was picking up a weapon of assault; but the judge was bending to creep under the counter. When he rose he was inside. He laid his cane on the counter and took off his coat.

"Here," said Mr. Almon, "what are you doing? We don't want a fight here."

"I'm not going to fight," said the judge, removing his waistcoat. "I'm going to take Tom Rollins's place. I'm going to show these infernal quitters and tinhorns that there is one real sport left in Riverbank. How do you get up on that seat?"

"Look here," said Mr. Almon, "you don't want to do --"

"Yes, I do," said the judge.

"But, look here," said Mr. Almon, "a judge can't do that. If you want to help us out, and are fool enough to want to be dipped, let me get some black from the minstrel booth, and nobody'll know you."

"I want 'em to know me," said Judge Deakin. "I want to square myself with this booth. I want you to get a crowd and have 'em give me just what they think they want to give me. How do you get up to that seat?"

"You climb up," said Mr. Almon, and took three of the baseballs in his hand.

"Three for a quarter," whispered Mr. Briggs. "You can get it easy!"

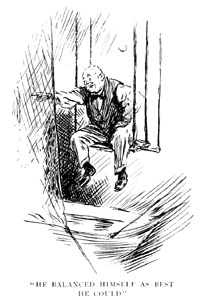

The judge was stout, and it was not easy for him to climb to the suspended seat, but he managed to get there. He balanced himself as best he could. The electric light glared full on him. He leaned forward and folded his arms across his chest.

"Now wait a minute," he said as Mr. Almon opened his mouth to utter the invitation to the crowd. "I want Sally Binton to have the first chance. Send over for her. Tell her I want her."

Mr. Briggs went. The crowd, seeing the Ethiopian Dip preparing for business, began to gather. Many recognized Judge Deakin, and the word began to spread. Mrs. Binton and Harry had to force a way through the crowd in front of the booth.

"Hah!" shouted Judge Deakin. "Here she is! Here she comes! Work off your spite. Watch the lady! Watch the lady!"

There is nothing attracts a crowd quicker than the sight of a woman throwing a ball. Mr. Briggs had to push back the crowd to make room for Mrs. Binton to swing her arm. She picked up three of the balls.

"Three for a quarter," said Mr. Almon.

"O you robber!" said Mrs. Binton. "Harry, give him a quarter. Now, Judge!"

She threw. The ball struck the net harmlessly.

"And she thinks she can throw a ball!" shouted the judge. "She thinks she can throw! She thinks she can throw. Yah!"

The second ball was so low Mr. Almon dodged involuntarily.

"Oh!" shouted the judge. "Almost, but not quite by a mile! She can't do it! She can't do it!"

The third ball struck the net and rolled down.

"A miss!" shouted the judge. "A miss by the missus! The lady has a glass arm. The only safe place is the spot she tries to hit."

"Harry, give him another quarter," said Mrs. Binton. "I'm going to duck that man if it takes all night."

"Oh, dear! she said after she had thrown twenty-one times. "Can't I do it?"

"I'm out of change," said Harry.

"Get my purse -- back of the red pot with the palm in it," said Mrs. Binton. "Hurry! Give me three more. I'll pay when Harry comes."

"Forty-one, forty-two, forty-three," counted the judge as the balls continued to patter harmlessly against the net. "She can't do it. She'll quit. She's no sport."

"Yes, I am, Judge!" she cried, and took up the forty-fourth ball. It traveled straight and true for the target. It struck the iron disk clean and true. The seat divided. Judge Deakin stopped in the middle of a word and fell, with arms and legs outspread, flat into the canvas tub. There was a mighty splash, and from the crowd a mighty laugh, and the small eyes and enormous nose of Judge Deakin appeared over the top of the canvas tub. Water dripped from the end of his nose and from every hair of his head. He was gasping, but he managed to speak.

"Here, somebody help me out of this! I'm so heavy-set I can't get out."

Mr. Almon and Mr. Briggs rushed to help him. They helped him to the suspended seat, and when the judge had wiped the water from his eyes and had shaken it from his ears, he saw Mrs. Binton, with her back to the counter, clapping her hands, and heard her shouting.

"Come on now! Come on now!" she was shrilling to the crowd. "Here's your chance to duck the most unpopular man in Riverbank, three chances for twenty-five cents. Come on and duck the unpopular judge!"

"They can't do it. They won't spend the money. I dare 'em," shouted the judge from his perch. "Oh, he missed a mile! His eye is as bad as his judgment."

"Come on! Come on!" cried Mrs. Binton. "Duck the unpopular judge!"

She was right in her adjective then, but wrong in using it when, at one o'clock in the morning, the carnival ended, for he was no longer the unpopular judge. The Fourth Ward Republican Club, counting its receipts, found them greater than those of any other booth. The crowd, going homeward, spoke of Judge Deakin with affectionate laughter.

"He may be wrong sometimes," they said, "but he's a mighty good sport just the same."

And Mrs. Harry Binton, having turned in the receipts of her booth and seen that everything was safe to leave for the night, came over to the Ethiopian Dip, where the judge and Mr. Almon were putting on their coats.

"Say, Deaky," said Mrs. Binton, "Harry and I want you to stop at the house on your way home. We're going to have something to eat and drink before we turn in."

"I'd love to, Sally," said the judge, "but I'm so infernal wet. I'm waterlogged. I've been ducked a million times. I'd love to, but I'm soaked."

And that was when Mr. Almon spoke up.

"Look here," he said, laying his hand affectionately on the judge's arm, "I'm going right home. Come around to the circus dressing-tent and we'll change clothes. It won't hurt me to wear wet clothes that long."

"It's my shoes that are the wettest," said the judge.

"Well, after tonight," said Mr. Almon, "I'd rather be in your shoes than in any other pair I know of. Hope you feel all right."

"I feel fine," said Judge Deakin. And he did.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 5:11:31am USA Central