| ||

| ||

from American Girl

The Locked Drawer Mystery

by Ellis Parker ButlerThat afternoon Dick Prince and Art Dane could not come to the meeting of our Detective Club because they had to attend a meeting of the sports committee at the high school. They said they might come later. There was nothing for us to detect that week so we settled down on Dot Carver's porch to read a few chapters of a mystery story.

"You read a chapter first, Madge," Betty Bliss said, handing me the book, and I had just opened it when I saw a girl stop at the front gate. She hesitated, looked at us uncertainly, then opened the gate and came up the walk. She was no one we knew. She was a plain-looking girl, quite simply dressed and old enough to be through high school, but what we all noticed first was the unhappy and worried look on her face.

"Please excuse me," she said, looking up at us from the bottom of the porch steps, "but is this Mrs. Carver's house? I went to Mrs. Bliss's house and she told me to come here. I'm looking for some girls who have a detective club."

Betty Bliss was out of her chair and at the head of the steps in an instant.

"This is the Detective Club," she said in the businesslike way she always speaks when she is being Superintendent Bliss of our Detective Club.

"The Club is in session this afternoon. Is there anything we can do for you?"

The girl seemed surprised.

"Why --" she said, "I thought you would be older than you are. The Detective Club I mean is the one that, I have been told, has been solving several mysteries --"

"We are the Club," said Betty Bliss. "I don't know of any other in town. This is Inspector Carver and this is Inspector Turner, and I am Superintendent Bliss. If we can be of any help to you we will be glad to serve you."

"I'm afraid I can't pay anything," the girl said as if she hated to have to say it. "You see, I haven't any money -- not much, anyway --"

"That," said Betty Bliss, "does not make the slightest difference in the world to us. We almost never detect for money. May I suggest that you come up and tell us what we can do for you?"

Betty said that in her grandest way, but she smiled as soon as she had said it and Betty has a nice friendly smile. The girl did not smile, but she came up the steps and took one of the chairs.

"I don't know whether you can do anything for me," she said, "but I am in trouble -- just awful trouble -- and I didn't know who else to go to. I've been -- well -- I've been accused of being a thief, and I don't know how to prove I'm not. It --"

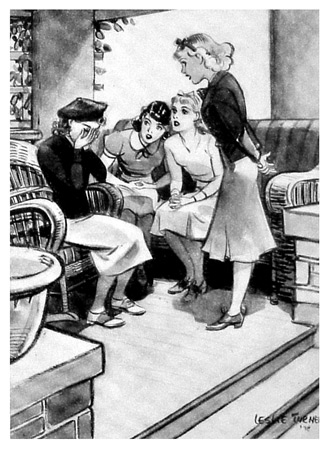

She stopped and hid her face in her hands. I thought she was going to cry, but she managed not to. After a minute or so she got control of herself and only wiped her eyes.

"It's a dreadful thing to be called a thief," she said, "and for me it is worse than for almost anyone because it means that, for me, everything is ended, and just when I am getting started."

"Tell us about it," I began, but Betty Bliss stopped me.

"If you please, Inspector Madge, I will question our client," Betty said. And to the girl, "Kindly give us all the facts you can -- name, age, circumstances of the crime, with all the details."

"My name is Mary Sloane," the girl said, twisting her hands. "I'm sixteen now, and I'm an orphan. When I was two years old they took me into Saint Elizabeth's Orphan Asylum, and a week ago I got through there -- we have to leave when we are sixteen years old. They get work for us, or put us in someone's home. Mrs. Joseph Branch took me."

"I know of Mrs. Branch," Betty said. "She is an important club woman. She is managing the Willing Hand Rummage Shop for the Town Aid Society now, isn't she?"

"Yes," said Mary Sloane, "and she was so good to me at first, and so kind. She gave me a nice room upstairs in her house, not really an attic. I thought I would be so happy there -- I don't mind doing housework, or washing dishes, or such things. But she has three servants already and she said I was to be her secretary if I could do the work."

"I should think she would need a secretary, being in so many clubs and all," Dot Carver put in, but Betty said, "Inspector! Please!" and Dot shut up.

"Of course, I was pleased," Mary Sloane went on. "I thought it would be fine, and so it was until this happened. Mrs. Branch is spending most of her time at the Rummage Shop just now and she took me down there to help her. Every afternoon. Some evenings. They are sending out hundreds of appeals for money, or old clothes, or anything the Rummage Shop can use, and I addressed envelopes. I write a good hand. Well --"

"Please continue, Miss Sloane," Betty said.

"Mrs. Branch handles all the money," the girl said. "She is president and treasurer."

"And she accused you of stealing the money!" I exclaimed. Betty Bliss frowned at me.

"No, not that," Miss Sloane said, "not exactly. Not much money, anyway. If you'll let me tell you?"

She looked at Betty Bliss and Betty nodded.

"That is just what we want," she said, "and the inspectors will please not interrupt. Go on, Miss Sloane."

"It was postage stamps mostly," Mary Sloane said. "You see, there were about a thousand envelopes ready to mail the first day I went there -- they use two cent stamps -- and Mrs. Branch gave me forty dollars and told me to go to the post office and get two thousand stamps, and I did. There were one hundred in a sheet -- that made twenty sheets of stamps. She took the money out of the drawer."

"One moment, please, said Betty. What drawer?"

"The drawer of her table -- she has a table she uses as a desk. Anyway, she gave me half the stamps to stick on the envelopes, and she put the rest in the drawer -- ten sheets, twenty dollars worth. There was some small change in the drawer -- petty cash, she called it -- and a few loose postage stamps, perhaps three dollars worth, three-cent ones and fives. Then she locked the drawer."

"Did she always keep the drawer locked?" Betty asked.

"Always," said Mary Sloane, "and kept the key in her handbag. She never let anyone else unlock the drawer -- so she says. When stamps were needed, Mrs. Branch unlocked the drawer and took them out and gave them to us."

"Who is 'us'?" asked Betty.

"There are three or four girls who work there part of the time -- society girls -- giving their time free. Mrs. Branch would never think they would steal."

"Anyone else work there?" Betty asked.

"Mrs. Overman, a rather elderly lady who is the paid manager," said the girl, "and a man named Comus Tooks, but I never saw him. He is the janitor and comes to clean up after we are gone."

"And all the money that is taken in at the shop is put in the drawer in Mrs. Branch's table?" Betty asked.

"Oh, no!" said Mary Sloane. "The money that the Rummage Shop takes in from selling things goes into the cash register, and that is most of the money. The cash register is always locked and no money was ever missing from it. The money that goes into the table drawer is money that people donate to help the shop along -- mostly checks -- and the petty cash Mrs. Branch needs to spend for small items the shop needs. The money from the cash register is put into the bank every day."

"Yes, I think I understand that," said Betty. "And you say you are accused of stealing? Tell us about that."

"Everything was all right until today," Mary Sloane said, trying hard to control her voice. "I've been helping Mrs. Branch just one week, and once a week she counts the stamps and the money in the drawer and balances her accounts. And today she said three dollars and forty cents were missing. She said no one could have taken it but me --"

At that Mary Sloane had to stop and hide her face in her hands again.

"Mrs. Branch said she couldn't keep me," she went on brokenly. "She said she couldn't have a petty thief about, and that I'd have to go back to the orphanage. And nobody will want me now -- nobody!"

"Does Mrs. Overman, the manager of the Rummage Shop, think you took the money?" Betty Bliss asked.

"I don't know," said Mary Sloane. "She didn't say anything -- I don't know whether she knows anything about it. Perhaps Mrs. Branch did not tell anyone there, but she'll tell them at the orphanage."

"Betty," I broke out, "I don't believe this girl took the money. I don't! She wouldn't come to us if --"

"When we are on a case you will kindly address me as Superintendent Bliss, Inspector Turner," said Betty severely, and did I feel my face getting red! "And why, Miss Sloane," she asked, "is Mrs. Branch so sure you are guilty?"

"Because I was the only one who could have taken it," said Mary Sloane. "Mrs. Branch always kept the key to the table drawer in her handbag, and I was the only one that was ever near her handbag alone. Mrs. Branch was always going to the front of the shop to talk with Mrs. Overman, or with some lady that came in, and she would leave her handbag on the table. It was always there within reach of my hand."

"And the others -- the society girls?"

"They were never there alone -- I was always there when they were. I was the only person that could have taken the key from the handbag to open the drawer."

"I see!" said Betty thoughtfully. "And your claim is, of course, that you took nothing from the drawer -- that you never opened it?"

"I never, never had the key in my hand! I never touched it! I never opened Mrs. Branch's handbag!" cried Mary Sloane. "I wouldn't do such a thing."

"But I suppose," said Betty, "you have some theory about the missing money -- or stamps?"

"Yes, I have," said Mary Sloane. "I think Mrs. Branch made a mistake. I think she counted wrong. Or maybe she took out some money or stamps and forgot about it -- forgot to make a memorandum of it. I told her so."

"Did that please her?" asked Betty with a smile.

"Oh, she was so angry!" exclaimed Mary Sloane. "She said she never made such mistakes and that I was impertinent to suggest such a thing. She said that in all the years she had been connected with clubs and associations and charities she had never made an error of a single cent."

"Superintendent Bliss --" I began.

"Never mind, Inspector Madge," Betty said.

"I know what you are going to say. But if Mrs. Branch has, this time, made an error in her accounting it does not help Miss Sloane any. No one, I am sure, could convince Mrs. Blanch that she made a mistake in her accounts. Certainly we girls could not. Miss Sloane, was the key an ordinary key? Could anyone open the lock of the drawer with a hairpin, for instance?"

"No," said Mary Sloane promptly. "It was a patent lock -- one of those with wiggly keys -- what do they call them ? No one could pick a lock like that."

"In other words, Miss Sloane," said Betty, "you are positive that no one could open the drawer without the key, and you are just as positive that no one but you or Mrs. Branch could have had possession of the key."

"Yes," said Mary Sloane, "I'm positive."

"Good!" Betty exclaimed. "That makes it very much simpler. Inspectors, I think the case is solved."

"Solved!" Dot ejaculated. "But I don't see --"

"Of course you do, Dot!" I said. "Betty -- I mean, Superintendent Bliss -- means that Mrs. Branch did make a mistake in her figures. But," I said, "I don't see how you are going to show her that she did, Superintendent Bliss. If she's so sure --"

But Betty was not really paying any attention to us. She was frowning, deep in thought, and when she spoke it was to Mary Sloane.

"Just what did Mrs. Branch tell you to do when she accused you?" Betty asked her. "Did she tell you to get your things from her house and go back to the orphanage?"

"Yes, she did," said Mary Sloane. "She said she did not want me to spend another night in her house. But I had heard the girls at the Rummage Shop -- the society girls who came to help Mrs. Branch -- talking about you and your Detective Club, and I thought I would come to you first. It was all I could think of to do."

"And quite right," said Betty, "but what will you do now?"

"I don't know," said Mary Sloane helplessly. "I'll have to get my clothes and go back to the orphanage, I suppose. I'll have to tell them."

"You have nowhere else to go?"

"No other place in the world," said the girl forlornly.

"No place where you can spend a night -- or perhaps two nights?"

"No place," said Mary Sloane.

"Well, you're not going back to that orphanage tonight with the story that you are accused of being a thief," said Betty Bliss positively. "Inspector Dot, will you ask your mother -- or, no! I'll ask mine. I'm going to use your telephone, Dot."

With that Betty went into the house and we others sat silent on the porch, waiting for her to come out. We heard her voice, but could not distinguish the words. It seemed to take Betty longer than was necessary and we wondered if she were having to argue with her mother, but when she came out again she seemed very much pleased.

"Mother was glad to be asked to give you a room for a night or two, Miss Sloane," Betty said, "and when you get your clothes from Mrs. Branch's, you can take them right to our house -- you know where that is because you stopped there on your way here. Mother will be there to welcome you. And," she said to us, "I telephoned to the high school and got Art and Dick on the wire, and they'll be here as soon as possible. They were just through with their meeting and were coming anyway. And I think, Miss Sloane, that you had better go to Mrs. Branch's at once and get your belongings. Mother will be expecting you."

Mary Sloane seemed almost overwhelmed by this. I honestly believe she would have kissed Betty's hand. There were tears in her eyes and she could not speak, but Betty assumed her most official manner.

"Our further instructions, Miss Sloane," she said, "are to avoid any controversy with Mrs. Branch if she happens to be there. I mean, don't quarrel with her. If she says anything unkind -- but I don't think she will -- just be silent. At the most just say, 'I am not a thief, Mrs. Branch.'"

"She wouldn't be there now," said Mary Sloane. "She'd be at the Rummage Shop now."

"So much the better," said Betty. "And don't be downhearted. Everything will be all right."

So Mary Sloane thanked us again and again and started on her way to get her clothes from Mrs. Branch's, and as soon as she was out of hearing Betty was all business again.

"Now then," she said, "we'll have to get busy. Inspectors, do either of you know Mrs. Overman, the manager of the Rummage Shop?"

"I don't," I said, and Dot said, "I don't," in the same moment of time.

"Then we'll have to find someone who does," declared Betty. "Dot, do you suppose your mother knows her?"

"She might," Dot said. "I know that Mother sometimes takes bundles to the Rummage Shop and no doubt she meets Mrs. Overman when she goes there. Shall I ask her?"

"Asking your mother if she knows Mrs. Overman seems to be indicated, Inspector," said Betty with a smile, and Dot went into the house. She came out in a minute or two with Mrs. Carver, who seemed pleased to be of service to us.

"Another mystery?" she smiled. "Dot asked me if I knew Mrs. Overman at the Rummage Shop. I do know her very well, much more than by merely meeting her there. As a matter of fact, Betty, she and I are members of the same church and have worked together in the Aid for many years. I'm sure you are not thinking she has done anything wrong; she is a lovely person, very kind and sweet."

"No, Mrs. Carver," Betty said, "we only want her help in removing suspicion from a person we believe is wrongly accused. We only want you to tell her who we are, and that we are not really just three silly girls."

"Certainly, I'll do that," said Mrs. Carver. "I'll telephone her now. Shall I tell her you are coming to see her?"

"Yes, please," Betty said, and in a few minutes Mrs. Carver told us it would be all right -- Mrs. Overman would be glad to see us.

Before Mrs. Carver had gone into the house Dick Prince and Art Dane came, all keyed up and excited by the news that we had another mystery case on our hands.

"What is it this time?" Art asked. "Tell us what we have to do -- we are all excited and raring to go! It must be something wild and woolly if you girls have to send for us. You're so smart you usually think you can get along just as well without any help from us."

"That's right!" Dick laughed. "It just shows. When it comes to a real mystery the ladies have to call on the good old manly brains to solve it."

"Really!" said Betty Bliss, a little huffed by their teasing. "We girls are very stupid, aren't we? Well, the mystery is solved, if you care to know it."

"It is?" asked Dick, quite naturally surprised. "And what was the mystery then?"

"Stolen money and stamps," said Betty. "They were kept in a locked drawer with only one key, and only two persons had access to the key, and neither one of them stole the money and stamps."

"The drawer was pried open," said Art. And at the same time Dick said, "Someone broke open the drawer."

"Wrong, both of you," said Betty, and as briefly as possible she told them about Mary Sloane and Mrs. Branch and the missing stamps and money -- it might have been either, or both.

"And you know who took the money?" Dick asked.

"Of course," Betty said. "There is only one person who could have taken it."

"Not Mary Sloane?"

"Certainly not."

"And not Mrs. Branch?"

"Don't be silly!" said Betty.

"And Mrs. Branch did not make a mistake in counting?" asked Dick.

"She says not," Betty answered.

"But see here!" exclaimed Art. "This is like one of those locked room mysteries -- every door and window locked and bolted on the inside, and yet the man in the room murdered. If nobody had a key to the drawer --"

"We're wasting time, Inspector," said Betty. "The afternoon is passing and we have quite a little to do. Any of you who have any cast-off clothes, or other rummage stuff, will please go and get it and we will all meet in front of my house in fifteen minutes. We are going to make a donation to the Rummage Shop."

In less than half an hour we were at the Rummage Shop and each of us had a nice little bundle to give Mrs. Overman.

There were two or three customers in the shop but they thought nothing of us, unless they thought we were five merry young people bringing donations. Mrs. Branch and her society helpers had gone home.

When Mrs. Overman had attended to her customers she came to us, and Dot told her who we were, and Betty explained that we were the Detective Club and that we were working on the case and what the case was. Mrs. Overman was a lovely person. This was the first she had heard of Mary Sloane having been accused of theft, and that proved that Mrs. Branch was not really cruel-hearted -- otherwise she would have told Mrs. Overman. Evidently Mrs. Branch did not want to be any harsher with Mary Sloane than she felt she had to be.

Mrs. Overman was as sorry for Mary as we were. She said she had thought Mary was a dear girl and that she would help us in any way she could.

"We would like to go to the back of the shop to inspect the scene of the crime, please," Betty said, and Mrs. Overman led us there. The small table was just as Mary had described it, and Betty knelt down and examined it carefully -- the slender legs, the top made of one smooth board, and the single drawer safely locked. Then she turned and looked at the walls of the room.

"Inspectors," Betty told us, "this is excellent! Here one can see and not be seen." She pointed to the rows of men's overcoats and women's coats and dresses hanging on racks at the far side of the room. "Inspectors Dane and Prince," she continued, speaking to Art and Dick, "there are some jobs that we girls really should not do, but you can do them if you are willing. One evening may be enough, or it may take several evenings, but you can be out of here in time to do your homework and get to bed."

"Out of here?" Dick asked. "You want us to hide here?"

"Yes," said Betty, "the only way to clear Mary Sloane is to catch the real thief, and I believe we can if Mrs. Overman is willing to let you boys hide behind those coats and keep watch."

"Quite willing," Mrs. Overman assured her.

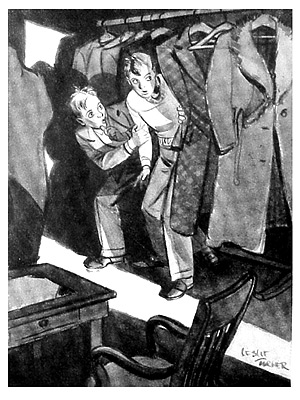

Art and Dick were eager to try it, so Betty and Dot and I went home, and when Mrs. Overman closed the shop and locked the door she left the boys hidden behind the coats.

In less than half an hour they heard a key turning in the front door lock, heard the door open and close, and Comus Tooks, the janitor, entered. He got a pail of damp sawdust and sprinkled it on the floor and began to sweep. He swept from the front toward the rear and, when he came to the small table, he stopped and stood the broom against the wall.

Art and Dick, peering out, saw him clearly. He reached into his pocket, drew out a hefty pocketknife, and opened the biggest blade. He pushed the blade in between the top of the table and the top edge of the drawer front, making a crack a quarter of an inch wide -- and then he turned the table upside down!

The rest was easy. All he had to do was tilt the table a little and shake it, and the loose change and the stamps slid out onto the floor. He bent down and began picking this up, putting some of the change and some of the stamps into his pocket and some back in the drawer.

Then Art and Dick stepped out from among the coats.

"That will do, Comus," Art said.

The janitor gave him one scared look and ran for the front door. He did not stop to lock it. Perhaps he never did stop -- he was never seen in our town again.

The boys left the pocketknife in the crack above the desk drawer, locked the shop, and came up to Betty's to report. She telephoned to Mrs. Branch immediately, and Mrs. Branch apologized to Mary Sloane and took her back, and everything was all right again.

"But, Betty," I asked, "how did you ever figure it out? How did you ever guess that Comus Tooks got the stamps out of the drawer that way?"

"Inspector Madge," Betty said, "don't you ever dare tell anyone, but that's how I got some money out of my own little table, the morning of the day Mary Sloane came to us. I keep change there -- locked up, you know -- and I had mislaid the key."

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 3:51:31am USA Central