from Century Magazine

Millington's Motor Mystery

by Ellis Parker Butler

Port Washington is about eleven miles from Flushing, and I have often wished to go to Port Washington; but Millington is absurdly jealous. Of course I could get to Port Washington on the train in about half an hour, or I could walk it in two or three, or drive there in an hour; but I know it would hurt Millington's feelings. He would take it as a personal insult to his automobile.

The very day I moved into my house, Millington came over and said he was glad somebody had moved in, because the last man that lived there was afraid of automobiles and would never take a spin with him. He said he hoped I was not afraid; and when I said I was not, he immediately proposed that we take a little spin out to Port Washington as soon as I had my furniture straightened around. I thought it was very nice and neighborly and unusual for a man with an automobile to begin an acquaintance in that way, for automobile owners are not usually that way; but I did not know Millington's automobile so well then as I grew to know it afterward.

I liked Millington. He was a short, Napoleon-looking man, with bulldog jaws and not very much hair, and I was glad to have him for a friend. I was particularly glad of this because I did not specially like the looks of my neighbor on the other side. Even as I was speaking to Millington, I saw my other neighbor leaning on his fence and staring hungrily at us. His name was Duggs -- Alonzo Duggs -- and he was a tall, lean, villainous-looking fellow, with a red, pointed beard, and as his hands rested on the top of the fence I could see his fingers opening and shutting like the claws of a bird of prey. I spoke to Millington about him, and all Millington said was: "Oh, he's no good. He won't ride in an automobile."

So, soon after that, Millington and I began to go to Port Washington in his automobile. As a rule we began to go every day, and sometimes twice a day, and I must say for Millington's automobile that it was one of the most patient I have ever seen. Patient and willing are the very words. It would start for Port Washington as willingly as anything, and go along as patient as could be. It was a very patient goer. Haste had no charms for it.

Millington used to come over bright and early and say cheerfully, "Well, how would you like to take a little run out to Port Washington today?" and I would get my cap, and we would go over to his garage and get into the machine and he would pull a lever or two and begin to listen for noises indicative of internal disorders. As a rule they began immediately, but sometimes he couldn't hear anything that could really be called serious until we reached the corner of the block. Once, I remember, and I shall never forget the date, we went three miles before Millington stopped the car and got out his wrenches and antiseptic bandages and other surgical tools; but usually the noises began inside of a block.

You see, Millington's automobile was just a little old. I shouldn't go so far as to say it was the first automobile ever made. It was probably the thirteenth, and Millington was probably the thirteenth owner. I know it had four cylinders, because he was constantly remarking that only three were working. Sometimes only one worked, and sometimes it didn't.

Our custom was for Millington and me to sit in front, while my wife and Millington's sat in the rear. There was a nice little gate in the rear by which they could enter. We would all get in, and Millington would pull his cap down tight and begin to frown and cock his head on one side to hear signs of asthma or heartthrobs or whatever the automobile might take a notion to have that day. And off we would go. I tell you, it was exhilarating. After all, there is nothing like motoring. We would roll smoothly down to the street, with Millington frowning like a pirate all the way, and then suddenly he would hear the noise he was listening for, and he would stop frowning, and jerk a lever that stopped the car, and hop out with a pleased, satisfied expression, and begin to whistle, and open the car in eight places, and take out an assorted hardware store, and adhesive tape, and blankets, and oil-cans, and hatchets, and axes, and get to work on the car as happy as a babe.

Usually when we started for Port Washington my wife and Millington's would dress for the matinee or church, or wherever they intended going that day, and when Millington got out his tools, they would excuse themselves politely and go and spend the day in the city. They usually got back in time to get into the car and ride back to the garage. But I stuck to Millington. You can never tell when a car of that kind will be ready to start up, and I was really very anxious to go to Port Washington. I spent some very delightful days with Millington that way, for when he was mending the car he was always in a charming humor, and as gay and playful as a kitten.

One of the most reliable noises for which Millington listened was a knocking in the motor-case. He was very fond of it, and it was one of the heartiest knockings I have ever heard in an automobile. It was something like the hiccups, only more strenuous. It was as if a giant had been shut in the motor by mistake, and was trying to knock the whole thing to pieces. The knock came about every eight seconds, lightly at first and then getting stronger and stronger until it made the fore end of the automobile bounce up a foot or eighteen inches at each knock. That was the noise that gave Millington the most pleasure and put him into the most pleasant mood, for he could never quite discover the cause of the knocking. He would do everything any man could think of to cure it, but the machine continued to knock. I remember he once even went so far as to put in a new inner tube to see if that would do any good; but it wouldn't. But there were plenty of other noises. Millington once told me he had classified and scheduled four hundred and eighteen separate noises of disorder that he had heard in that one automobile, and that did not include any that might be a different noise of the same disorder. And some days he would hear the whole four hundred and eighteen before we had gone a block. Those were his happy days.

Well, one day Millington came over and said cheerfully, "Well, boy, how would you like to take a little run out to Port Washington today?" I was willing. My wife was just putting a cake in the oven, and she only took time to tell the maid that she would be back in time to take it out, and then we went over to Millington's garage. Mrs. Millington was already in the automobile, and my wife and I got in, and Millington opened the throttle, and the machine ran down the path to the street as lightly and skimmingly as a swallow. It glided into the street noiselessly, and headed for Port Washington like a thing alive. I noticed that Millington looked anxious, but I thought nothing of it at the time. His brow was drawn into a deep frown, and from moment to moment he pulled his cap farther and farther down over his eyes, and he was leaning far over the side of the car. He was listening so closely that his ears twitched with the exertion.

Mrs. Millington and my wife were chatting merrily on the rear seat, and I had just turned to cast them a word, when the car came to a stop. I turned to Millington instantly, ready to catch the pleasant bit of humor that he usually let drop when he began to dig out his wrenches and pliers, but his face bore a horrid glare of anger. His bulldog jaws were set, and he was muttering low, intense curses. I have never seen a man so nearly a demon as Millington was at that moment. I asked him merrily what was the matter with the old junk-shop this time, but instead of his usual chipper repartee that "the old tea-kettle has the epizootic," he gave me one ferocious glance in which murder was plainly to be seen.

Without a word he began walking around the automobile, eying it maliciously, and every time he passed a tire he kicked it as hard as he could. Then he began opening the opening parts, and when he had opened them all and peered into them long and angrily, he went over to the curb and sat down and swore. My wife and Mrs. Millington politely stuffed their handkerchiefs in their ears, but I went over to Millington and spoke to him as man to man.

"Millington," I said severely, "calm down! I am surprised. Time and again I have started for Port Washington with you, and time and again we have paused all day while you repaired the automobile. Much as I have wished to go to Port Washington, I have never complained, because you have always been better company while repairing the machine than at any other time. But this I cannot stand. If you continue to act this way, I shall never again go toward Port Washington with you. Brace up and repair the machine!"

Millington's only answer was a curse.

I was about to take him by the throat and teach him a little bit of manners when he arose and walked over to the machine again. He got in and started the motor, and listened intently while I ran alongside. Then with a great effort he controlled his feelings and spoke.

"Ladies," he said between his teeth, "we shall have to postpone going to Port Washington today. I am afraid to drive this car any farther. There is something very, very serious the matter with it."

Then, when the women had disappeared, my wife walking rapidly, so as to arrive at home before her cake was scorched, he turned to me.

"Bobs," he said with emotion, "you must excuse the feeling I showed. I was upset; I admit that I was overcome. I have owned this car four years, but in all that time, although I have started for Port Washington nearly every day, the car has never behaved as it has just behaved. I am a brave man, Bobs, and I have never been afraid of a motor-car before, but when my car acts as this car has just acted, I am afraid."

I could see that he spoke the truth. His face was white about the mouth, and the tense lines showed how he was nerving himself to his duty. His voice trembled with intense self-control.

"Bobs," he asked, taking my hand, as if the touch of something human was a relief -- "Bobs, were you listening to the car?"

"No," I had to admit. "No, Millington, I was not. I am ashamed to say it, but at the moment my mind was elsewhere. But," I added, as if in self-defense, "I am pretty sure I did not hear that knocking. I remember quite distinctly that I was not holding on to anything, and when the engine knocks -- But what did you hear?"

A shiver of involuntary fear passed over Millington, and he lowered his voice to a fear-struck whisper. He glanced at the automobile.

"Nothing," he said.

"What!" I cried. I could not hide my astonishment, and, I am afraid, my disbelief. I would not for the world have had Millington think I thought he was prevaricating.

"Nothing," he repeated firmly. "Not a sound; not a bad symptom. Every -- everything -- everything was running just as it should -- just as they do in other automobiles."

"Millington!" I cried reproachfully.

"It is the truth," he cried. "I swear it is the truth. Nothing seemed broken or going to break. I could not hear a sound of distress or a symptom of disorder. Do you wonder I was overcome?"

"Millington," I said seriously, "this is no light matter. It is a very serious matter. I shall not accuse you of willfully lying to me, and yet I cannot believe that your automobile could proceed four hundred feet without making noises of internal disorder. It is evident to me that your hearing is growing weak; you may he threatened with deafness."

At this Millington seemed to cheer up considerably, for deafness was something he could understand, and I proposed that we both get into the automobile again and that I would listen myself. So we did that. It was almost pathetic, it was most pathetic, to see the way Millington looked up into my face to see what verdict I would give as he started the machine. My verdict was the very worst possible. We ran a block at low speed, and I could hear no trouble. We ran a block at second speed, and no distressful noise did I hear. We ran two blocks at high speed, with no noise but the soft purring of the motors and machinery. As he brought the automobile to a stop we looked at each other aghast. It was true, too true; there was nothing the matter with the automobile: it sparked, it ignited, it did everything a perfect machine should. We got out of the machine and stared at it silently.

"Bobs," said Millington at length, "you can easily see that I would not dare to start on a long trip like that to Port Washington when my automobile is acting in this unaccountable manner. It would be the most foolhardy recklessness. When this machine is running in an absolutely perfect manner, almost anything may be the matter with it. My. own opinion is that a spell has been cast over it, and that it is bewitched. I cannot think of anything else that would make it behave as an automobile in good health should. I am going to walk home. As for you, as it was entirely for your sake that I proposed this little run out to Port Washington, I am going to put the machine in your charge, and you are to run it around the block until it resumes its normal condition. From what I know of you and of the remarks you have made while I have repaired the motor in the past, I believe you will soon have it making some sort of noise, and," he added with a hopeful smile, "perhaps it will be making a noise it never made before." Then he showed me what to touch to start the machine, and what to touch if a tree or telephone post got in my way; and then he went home.

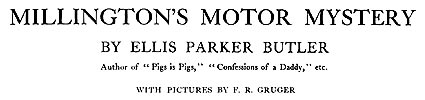

I was much touched by this evidence of Millington's faith in my ability to bring out the bad points of his automobile, and as soon as he had disappeared, I set to work, and I had hardly gone twice around the block before I had it knocking even more loudly than I had ever heard it knock. But I was resolved to show Millington that his trust was not misplaced, and I ran the nose of the machine into a tree, and threw on the high speed suddenly, until I heard the sweet noise that told me the gear was stripped. It was then necessary to get a team to pull the automobile home, which I did, and I shall never forget the pleased expression on Millington's face as he saw the helpless machine being towed into his yard. I felt rightly proud at having lifted such a load from him.

"Now," he said as cheerfully as was his wont, "we can all start for Port Washington in the morning. I will get up at four and tinker at the motor, and by nine, or ten at the latest, we will be ready to start."

At nine the next morning, therefore, my wife and I went over to Millington's garage, but our first glimpse of him told us that all was not well. He was sitting on the garage step with his head buried in his arms, while his wife was sitting beside him, vainly endeavoring to console him. For a while he made no response at all to my queries, and then he only raised his woeful face and pointed mutely at the automobile. He was too overcome for words, and his wife had to tell us the awful facts.

"This morning at four," she said, "Edward came out and prepared to do what he could to the motor you so kindly put to the bad. He was then his usual cheerful self. He leaped lightly into the chauffeur's seat, touched the starting-lever, and, to his utter distress, the automobile moved smoothly out of the garage and down the driveway without a single misplaced throb or a sign of disorder. There was nothing the matter with the automobile at all, nor a thing to repair. It was in perfect shape. It was as if it had just come from the factory. Of course he immediately gave up all idea of the little run to Port Washington. Now, there is only one thing for us to do. Bob must take the machine and run it around the block until it is in fit condition to be repaired. I am afraid he did not do a good job yesterday."

Although I felt rather hurt by the last words, I was not a man to desert Millington in his need, and without a word I jumped into the automobile and started. That day I worked hard. It seemed as if nothing would ever be the matter with that automobile again, but by persistent efforts and by doing everything an amateur could possibly do to ruin an automobile, I at last succeeded in developing its weak spots. It was not until nine at night that I was satisfied; but when the horses at length pulled the automobile into Millington's garage I felt that I had done my duty. I had mashed the hood and cracked a cylinder, dished the left front wheel, and absolutely ruined the batteries. I would have defied any man to make the automobile run an inch. It had been hard work, but I was amply repaid when Millington threw his arms around me and wept for joy on my shoulder. He was not a demonstrative man.

"Next week, or the week after, Bobs," he said to me cheerfully, "I will have the machine in fair shape, and we can take a little run out to Port Washington. I feel that the trip has been delayed too long already, and I shall get to work at three tomorrow morning."

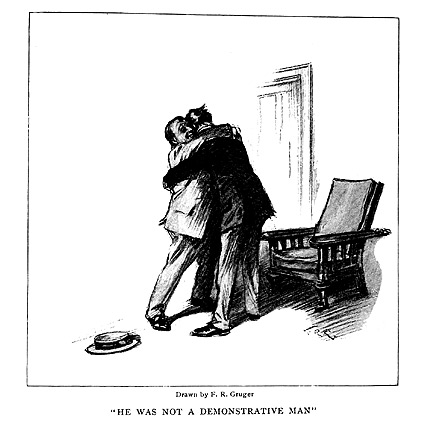

It is always a pleasure to me to see another man happy, and at half-past two the next morning I was waiting for Millington at his garage door. He came out promptly at three, joking merrily as he unlocked the door, but the moment he opened the door his face fell. And well it might. The dished wheel had been trued, the crushed hood had been straightened and painted; the crack in the cylinder was gone, and when Millington tried the motor, it ran without a sound except that of the perfectly palpitating ignition. Millington got out of the car and stood staring at the motor, and suddenly he uttered a low cry of anguish and fell over backward as stiff as a log. Mrs. Millington and I managed to carry him to bed, and then I returned to the car. I was not going to desert Millington in his adversity. I got into the car, ran three blocks down the street, got out, aimed the machine at a stone wall, threw on the high speed, and jumped to one side. One minute later the only way the machine could be got back to the garage was to load it on to a truck. When I told this to Millington he sat up in bed and took a little nourishment, and by night he was almost himself again. As for myself, I went home and went to bed at once, for I knew that, in order to get the machine in order for a little run to Port Washington, it would be necessary for Millington and me to get up soon after sundown.

At ten o'clock, therefore, I was out of bed again, and I went over to Millington's. I found him in bed and awake and fairly cheerful, but he would not get up. He said it was against his policy to get up the day before in order to get up in the morning, so I read him chapters out of a dear little work of fiction on "Ignition Troubles," until the clock struck twelve, and then he hopped out of bed and threw on his clothes.

The moment we stepped out of the back door the same thing struck us both with surprise. There was a light in the garage! My first thought was that some rascal was in the garage trying to ruin Millington's automobile, but a second thought assured me that this was impossible. Ruin could be carried no farther than I had carried it. Bidding Millington be silent, I crept cautiously toward the garage, with Millington at my heels, and without a sound we peered in at the window. The sight was one that would have shaken the strongest man.

Bending over the motor, with his face made unearthly by the artificial light that fell upon it obliquely, casting deep shadows, was that villain, Alonzo Duggs! I have never seen anything so devilish as that wretch as he worked with inhuman agility and haste. His long clawlike fingers danced from part to part fiendishly, and a hideous grin distorted his features. He was humming some weird tune, and I noted that he was ambidextrous, for he was varnishing the hood with one hand while with the other he was putting in a new sparking-plug. A tremor of horror passed over Millington and me at the same moment. A few whispered words, a few stealthy steps, and we burst in and seized him by the arms. In a moment more we had him on the floor of the garage, bound hand and foot.

Millington was for wreaking immediate vengeance on him, but I stood firmly for a more lawful course, and the next day we handed him over to the authorities, and his whole miserable story came out. His name was not Alonzo Duggs at all. It was William Alexander Gribbous. He came originally of a good family, but speed mania had brought him to ruin, and the third time he was arrested a sentence of thirty years had been imposed upon him. The judge, however, had suspended sentence, provided that he never again touched an automobile. For several years he had fought down his appetite. Then he fell. He changed his name, and secured a position as Mlle. Zozo, the death-defying loop-the-gappist, with the big show. For a time the speeding down the runway and turning a somersault in the fake automobile appeased him, but the rules of the show prohibited him from tinkering with the automobile, which was strictly in charge of the property-man, and he left the show, changed his name to Alonzo Duggs, and, seeking our quiet town, chose a house nearest the man with the oldest automobile. For weeks he watched his chance; you know the rest. He is now in Sing Sing.

I am sorry to end this story so abruptly, but Millington has just come over to ask me if I would not like to take a little run out to Port Washington. I have always wanted to go to Port Washington, which is only about eleven miles from here, so if you will just excuse me, I'll go and button my wife's matinee gown, and we will be off.