| ||

| ||

from Every Week

Scratch-Cat

by Ellis Parker ButlerWell, Mamie Little was my girl because she had nice curls; and my sister was Eddie's girl, and he thought it was all right, because he didn't know any better; but she made me sick. She thinks she's too smart but she's all freckledy and snubby nosed,

Whenever me and Mamie and Eddie and my sister played house, or anything, my sister would twist her hair up on top of her head and tell Eddie he was her husband Whenever she would run or jump, she would take Eddie's hand and hold it against her side and say: "Oh, Eddie! just see how my heart is beating!" I guess it made Eddie feel pretty sick and foolish, having his hand held up against her side like that.

But that's the way my sister was. She made me sick, and I told her so. I've told her a million times, but it don't do any good.

So most of the fellows had girls. But you bet Ting didn't! He was too good a fighter. Nobody dared holler at him.

The way fellows come to have girls is like this: First they don't have any, and then some fellow that can lick them yells at them:

"Georgie! Georgie! Georgie!

Mamie Little's your girl!"Or something like that. But she ain't. So you yell back:

"Aw! shut up! she ain't, neither!"

So whoever the fellow is yells back at you:

"She is tiether! She is tiether!

"Georgie porgie, pudden' an' pie.

Kiss Mamie Little and make her cry!

Georgie porgie. pudden' an' pie,

Kiss Mamie Little and make her cry!"So then, if you are big enough, you go over and lick the fellow, unless he is a girl. But if you ain't big enough you get so mad you blubber, and you go across the street and try to lick him anyway. Because Mamie Little ain't your girl, and you know she ain't. So when you've licked him, and proved she ain't your girl, why, then she is your girl. You don't know how she got to be, but she is. So all you can do is to feel pretty mean and cheap, because that's how a fellow always feels when anybody is his girl.

But girls don't feel that way when they have fellows. Right away they begin to wiggle their skirts when they walk, and want their mothers to curl their hair every day and put fresh blue hair-bows on them. So then they start right in saying how they hate the fellow that's their fellow; but they take slate pencils and apples and things from him when he gives them on the sly, and they begin writing notes to him in school, like "Don't you think you're smart with your new necktie?" and things like that. So he feels pretty good after all, and gives her apples when nobody is looking, and pushes her around mean-like when anybody does look.

But she don't mind being pushed around, because that's how she knows he is her fellow. So when there is a party she's the one he drops the pillow before, and if she don't kiss him it is all right for her! But mostly she does. She lets on she hates it, but she don't. She likes it.

Well, one reason Ting didn't have a girl was because he was such a good fighter nobody dared yell at him I guess the other reason was that nobody ever thought of yelling at him that anybody was his girl. He never sort of walked on the edge of the sidewalk when the girls were walking in the middle of it, or cut up funny to make them look.

As soon as school was out he began clod fighting with the graveyard gang, or made a beeline for the baseball lot, or got up a good fight. It was boys he liked to push around, and not girls. Maybe one reason he didn't have a girl was because his father and mother were Dutchmen, so the girls didn't want a Dutchy for a fellow, because most of the Dutchmen worked in the sawmill. But Ting's father didn't. He was a tailor. Only his name was Schwartz, so maybe that was the reason. Girls don't like to have fellows yell at them: "Aw! you got a Dutchman for a fellow!" because when anybody sees a Dutchman they yell:

"Dutchy! Dutchy! Sauerkraut!

Your shirt-tail's a-stickin' out!"Well, one vacation time there was a new girl came to Riverbank. She lived in the little house across Main Street that has a picket fence and a yard that runs mostly down the bank, and the first I knew about her was one day when I had to go downtown on an errand and went that way.

I had on some new shoes, so I knew everybody in town would see them and be thinking about them, and I felt pretty mean; and when I went by the little house the girl was behind the picket fence, looking. So I made a face at her, because it was none of her business if I did have new shoes.

It was summer, of course, and hot; but the girl had on a woolen dress -- red and black checks -- and it fitted her pretty tight all over and was too short and little, so that it was tight like skin, and her wrists stuck out too far. She was barefoot, too. That was funny, because girls don't go barefoot.

I was going to yell something at her, but I didn't, because it was just as funny for a boy to have shoes on, and she might yell back. She didn't know that the reason I had shoes on was that company was coming to dinner.

So I only made a face at her. But she didn't make one back at me. She just looked.

She wasn't like any girl in Riverbank that I ever saw. She was pretty much tanned brown, but she had reddish cheeks, and her hair was as black as Sunday shoes and cut short, like a boy's, only it was banged in front, and her bangs were so long they came down to her eyebrows, and they were black too. She stood behind the picket fence and just looked, and I didn't like it. Her eyes were black, too.

So I whistled and looked the other way, and the first thing I knew she was out of the gate and after me. I tried to run, but she cornered me and took me by the hair and jerked me back and forth. I thought she was going to jerk my head off. So I pulled loose and ran, because no girl can jerk me around by the hair like that. So all she got for her smarty business was just a handful of hair or two. And who cares for a handful of hair?

Well, you bet I got even with her, all right! I never went past her house alone after that.

So that's the way she was. She stayed in her yard, and when a boy came along she would jump out and grab him by the hair, or slap him, and chase him away from in front of her house. She was a tartar, all right. She was like a spider that is always waiting and comes out and grabs flies; only what she grabbed wasn't flies -- it was boys. So we all got afraid of her, and we didn't dast go past her house unless we were two or three together. And then we generally went round some other way. Except Ting.

Because one day Ting he went past her house, and she come out and was going to pull his hair, like she did the rest of us; and when she came at him he backed up against the fence, and when she reached out for his hair he hit her hand away with one hand and slapped her on the face good and plenty. He slapped her two or three times and dared her to touch him. So she didn't say anything, and Ting didn't say anything, and they just stood there. And pretty soon Ting went on downtown. So she just stood there, me and Eddie had to play with girls sometimes, because Mamie Little was my girl and my sister was Eddie's girl. Or maybe we did like to play with girls a little sometimes, because they let us be the husbands and fathers, and boss them around and whip the children. So when we did Ting used to come along. Mostly he would sit and whittle until me and Eddie got through, but sometimes he would be the policeman to arrest the husbands when they got drunk, or a pirate, or an Indian lurking to scalp the wives, or a 'rangatang to carry the children off. I guess the girls wished he wouldn't come, because a 'rangatang is such an interruption to plain housekeeping, and pirates and policemen are an awful nuisance to mothers who want to bring up a peaceful family and don't want their husbands taken to jail just when the mud pies are cooked and dinner is ready. But they couldn't help it, because if they didn't let him me and Eddie would go where Ting went.

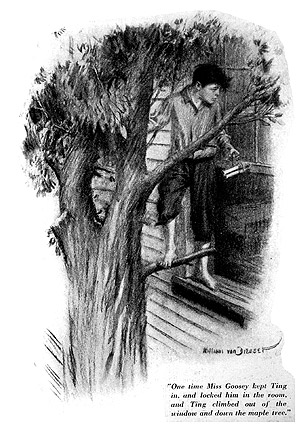

Well, one time when Miss Goosey kept Ting in school to have the principal lick him, she went out to get the principal and locked Ting in the room, and he climbed out of the window onto a maple tree branch and got away. So the principal licked him the next day. Anyway, the trees darkened the room all up, so when it came vacation time the janitor cut down the two trees and they fell down the bank back of the schoolhouse.

So that day the leaves were only beginning to wither, and the branches of the trees made a bully place to play in. So Mamie Little and my sister and me and Eddie went right out there after dinner and played house; and when Ting had been licked, or whatever he had been kept home for, he came there too. We made houses among the branches and leaves, and were fathers and mothers; and Ting had a lair and was a 'rangatang, and hung by his knees and swang from branch to branch.

It was pretty good fun, even if it was playing with girls, because it was a jungle, and me and Eddie hunted the wild 'rangatang between meals; and we were playing along all right when I saw my sister standing and looking. I guess you know how a girl stands and looks -- the way a cow does -- when she don't like something. So I looked, and out in the street was the girl in the red and black check woolen dress. She was just standing and looking back at my sister. It made my sister mighty mad. I guess girls can look the things boys generally holler at each other. So my sister said:

"Eddie, I don't want that girl to look at me!"

So Eddie looked, and when he saw who was looking he said:

"Aw! let her look! Let her look, if she wants to. She ain't hurting anybody!"

So then my sister got awful mad. She stamped her foot.

"I won't let her look at me that way."

So she started on a run for the girl. She didn't get quite up to her. Before she got quite to her, the girl sort of flashed up to my sister. That was about all I could see. The next I saw, she was standing just where she had always been, and my sister was flopped down on the ground with her arms over her head, yelling blood and murder. So I jumped out of the tree and ran up to my sister. Her face was all scratched up. There were four long scratches on each side of her face where the girl had raked her with her claws. So Mamie Little came running too, and helped my sister up.

"If I was a boy," she said, "I wouldn't let anybody do that to my sister unless I was a 'fraid-cat."

"Aw! who's a 'fraid-cat?" I said. I wasn't no more 'fraid-cat than she was, but I guess I knew that girl.

So Mamie Little took my sister by the arm.

"Come on," she said. "I guess everybody around here is a 'fraid-cat. You and me will be mad at them and stay mad for ever and ever!"

So I had to go. I wasn't going to hit the girl. I just thought I'd sort of push her away -- only maybe a little rough -- until I pushed her inside her gate, so I could show a smarty like Mamie Little who was a 'fraid-cat and who wasn't. I walked over to where the girl was, and she waited for me. All I had time to see was the girl's eyes turning to something like prickly black fire, and something plumped against me like a bag of flour shot out of a sling. It was as if her body hit against me everywhere at once. And then something grabbed my hair and yanked me, and I felt scratches burning on my face, and, somehow, I was on the ground, yelling and holding my arms above my head. The girl was standing where she had always been. I heard Mamie Little and my sister yelling:

"Scratch-cat! Scratch-cat!"

Ting came on the run. He was pretty mad, because him and me was chums, and I was his cow-cousin and his double Dutch uncle, and he ran right past me and up to the girl. He gave her a push with his hand, and it sort of pushed her around; but she straightened up again and just looked at him.

"You scratch-cat!" he said, as mean as he knew how. "Who are you scratching around here, I'd like to know?"

I thought she'd jump on him and claw him, like she did me; but she didn't.

"I ain't going to hurt you," she said.

"You bet you ain't!" Ting said. "'Cause why? 'Cause you daresn't, that's why!" Only he said, "'Cors why?" like he always does.

She didn't say she did dare, and she didn't say she didn't dare. She said:

"Come over in my yard and play with me. Don't you play with them. I can play good."

So Ting pushed her again, and she stepped back a step.

"Don't you play with girls!" she said. "You come and play with me."

"Aw! you're a girl too," Ting said. "Go awrn home and play with yourself."

So he gave her another push. She looked as if she hadn't ever thought that she was a girl before. She said:

"I can beat you running. I can beat you jumping. I can beat you climbing trees. I can beat you skinning the cat. I can chin myself ten times more than you can. I can stand on my head longer than you can."

"Go awrn home!" Ting said, and gave her another shove.

She stepped back again.

"Come on and play in my yard," she said again. "I can throw you any hold you want. I can fight you and lick you."

"Becors you're a scratch-cat," Ting said, and pushed her again.

"I can lick you without scratching," the girl said.

"Well, then, do it!" said Ting. "Go on and do it, why don't you? I want to see you do it!"

So each time he said it he gave her a push.

"I won't!" she said. "I ain't going to fight you."

"You daresn't!"

"I ain't going to!"

"You don't dare!"

"I ain't going to!"

So every time Ting said anything he shoved her again, and pretty soon he had her pushed clear back against the fence of her yard, and he left her there and came back. We went on playing. But every once in a while we thought of her, and when we looked she was standing just where Ting had left her.

Well, we found out her name was Dell Brown, because my father went to speak to her father about the way she scratched my sister. Her father's name was Reverend Brown; but he had adopted her because her folks died, and she was a sore trial, but no doubt willed by the Almighty. The Reverend Brown was a sort of preacher, and had an old white horse and drove around the country and preached wherever he thought they needed preaching. Mrs. Brown was a sort of invalid and old, like Reverend Brown was, and he was almost too old to adopt Dell Brown for his daughter. He had ought to have adopted her for his granddaughter when he was adopting.

So he said he would pray about it, and Mrs. Brown said she couldn't understand Dell Brown, hardly, why she had the fighting streak in her, because at home she was all love and affection to Mrs. Brown, and a word made the child weep. I guess Dell Brown had just so much fight in her and had to get it fought out. I guess she thought it was better to go out and fight than to fight Mr. and Mrs. Brown. Maybe she was sort of fond of them because they were funny and old and had adopted her. I guess she was like George Washington: she was good and nice, but she liked to fight.

Well, after while school started again. I kind of hated to go, because I always hate to, but more because I thought Dell Brown would go to school. So she did, and the first time she got me alone she took me by the hair and walloped me good. I hadn't done nothing to her, except maybe yell "Scratch-cat!" at her sometimes when I was far enough away. So after that I didn't go to school very early, but kind of hung around until Dell Brown went in, and then I went in. I never told on her. If she says I did she tells what ain't so. It was Muddy Harrington.

Me and Ting was kept in that day, like we 'most always were, and Eddie was waiting outside. So Miss Goosey thought it wasn't any use talking to Dell Brown any more; it was time to rawhide her. She got the rawhide out of the closet, and told Dell Brown to come to the back of the room, and Dell Brown went. Miss Goosey put one hand on Dell Brown's shoulder, and lifted up the whip to switch her across the legs, and the next thing she did was to let out a scream, and you couldn't have believed her dress could be torn so in just a second if you hadn't seen it. Her hands were beginning to get red in streaks where Dell Brown had scratched them. So Dell Brown just threw Miss Goosey's hair switch on a desk, and stood there with her chest swelling in and out under her red and black checked dress, and Miss Goosey backed away and began winding her switch on her head again.

When Miss Goosey got her hair on, she went out and locked the door and got Professor Marston, the principal, who is her beau. He came in, and he was pretty mad. He grabbed Dell Brown and gave her a shake, and she flew at him like a cat and scratched him across the face. He slung her around, and she hit a desk and fell on the floor. It made her cry, and Professor Marston was scared of what he had done and went to pick her up. But when he stooped she clawed at him and scratched his other cheek, and he left her alone and told her to get up and go home, because she was expelled from school.

So Dell Brown got up, and held her hand to her side, and went and got her books and went home. But there was only one rib broke, and I guess it healed all right, because she was young and tough. But nobody whipped any more girls in school. I guess they thought it was safer to whip boys. They are more used to it, and their ribs ain't so brittle. Or maybe the school board stopped it. Professor Marston got fired because he had broke a rib for Scratch-cat, and he went to Derlingport and got five hundred dollars more a year and another sweetheart, because Miss Goosey cried a lot that term.

Well, of course; the expelling didn't take, and Dell Brown came back. She didn't fight much, because her rib was brittle yet; but she was mad at Miss Goosey, and Miss Goosey was mad at her because Professor Marston had had to go away and love somebody else. She never talked to Dell Brown like she did to the other girls, or let her be monitor or anything. She would say: "Mamie dear, can you tell me the answer?" and then she would say to Dell Brown: "Next girl?" I guess she hated her.

One day Miss Goosey was walking down the aisle, and she had some flowers pinned on, and one dropped in the aisle, and Dell Brown picked it up and put it in a book. She used to open the book there and look at the flower. She used to sit and look at Miss Goosey, and you couldn't tell whether she was mad at her or not, because her face was so dark and her eyes so black. But I guess she wasn't mad. I guess she wanted Miss Goosey to like her, but didn't know how to make her.

None of the girls played with Dell Brown, because she was a scratch-cat; and none of the boys played with her, because they were afraid of her. As soon as school was out she would go home and play in her own yard. I guess she was pretty lonely.

Well, it got along until it was the hind end of September and going on October, and the weather was bully and warm. It made you want to do things. So on Saturday me and Ting and Eddie was sitting in my barn and talking about what we would do that afternoon. We thought of a lot of things, and said them; but every time Ting said: "Aw! no, let's don't!" so we didn't. So then I said:

"I tell you what!"

"What?" Ting asked.

"Pshaw, no!" I said. "It ain't no use. We couldn't got any. It ain't the time for them?"

"Aw! what you tarlkin' about?" Ting asked. "What ain't it the time for?"

"Pond-lilies," I said. "If it was time for pond-lilies we could go up the river to the pond-lily pond and get some pond-lilies."

So then Ting he talked up.

"Well, we could row up the river anyway, couldn't we?" he said -- only he said "rowr" instead of "row," like he always does. "We could rowr up the river and get some pond-lily roots and sell them."

"Aw! who would buy old pond-lily roots?" Eddie wanted to know.

Well, I thought at first that the reason Ting said We could sell pond-lily roots was because once I had told him about a man or somebody who had made money getting pond-lily roots and selling them to people who wanted to raise pond-lilies in a tub in their gardens. But that wasn't why he said it.

"Why, garsh! plenty of people would want to buy them," Ting said. "I guess I ought to know. I guess I've got an uncle in Derlingport, ain't I? I guess he ought to know about pond-lily roots, oughtn't he?"

It looked like that ought to be so, because Derlingport is three times as big as Riverbank, and Ting's uncle was older than any of us. But Eddie said:

"Aw! what does your old uncle know about pond-lily roots, anyway?"

"I guess he knows plenty about them," Ting said. "I guess if you went up to Derlingport to visit him you'd see whether he knows anything about them or not! I bet my uncle is the richest man in Derlingport, and the reason he is is because once, when I was out pond-lilying, I sent him a pond-lily root and he grew it in a tub, and when folks saw it they wanted to grow some too. So my uncle he rowred up the river to a pond-lily pond, and he got some roots and sold them. First orff he only got a few and sold them; but pretty soon he had a hundred men getting pond-lily roots for him, and he had to build a pond-lily root elevator, like the grain elevator down on the levee, but ten times bigger."

"Gee-my-nenlily!" said Eddie. "Ten times bigger! Gosh!"

"Ho, that ain't nothing!" Ting said. "That was when he was just beginning to start out. He's got ten of them elevators now, and -- and he's got almost ten trillion-billion pond-lily roots in them. He's got a railway switch and a steamboat dock to each elevator, and when he ships pond-lily roots he ships them by the trainload. Only, when he sells them in Dubuque or Keorkuk, he ships them by the boatload."

"Gee-my-nentily!" said Eddie again. "Come on! Let's -- "

"Well, I guess so!" said Ting. "I guess it's no wonder he's the richest man in Derlingport! And I can just go and visit him any time I want to. I can go visit him and take a bath right in his china bathtub."

"Aw! go on!" I said. "He ain't got a china bathtub!"

"Yes, sir! just like a teacup."

"Gosh!" Eddie said. "Did you take a bath in it?"

"Garsh, no!" said Ting. "Do you think I'd go taking bathtub baths when I didn't have to? When I visit him my uncle lets me do just what I want to. I don't have to wash my feet, or take a bath, or go for a cow, or fetch in wood --"

"Who fetches in the wood?" Eddie asked.

"Nobody," Ting said. "My uncle don't burn sawmill slabs or cord wood. He burns coal."

"Well, somebody has to fetch in the coal, don't he?" I wanted to know.

"Well, I guess not!" said Ting. "He -- he has a -- a bridge built right over the top of his house, so he can run a railroad over it, and he has a big iron box on top of his house under the bridge, and the railroad hawrls the cars of coal right up on top of the roof and dumps the coal into the iron box, and it runs down the chimbleys right into the stove."

Well, me and Eddie didn't say nothing. We just sat there and thought what we thought.

"And he's got a road scooped out under his house for a railroad to run on," Ting said, "and there is always a train of cars under the house, and when my uncle, or anybody, shakes the grate the ashes fall right down an iron pipe into the cars."

"Come on!" I said. "Come on! Let's go somewhere."

So Ting looked at me; but I hadn't said he was a liar or anything, so there was nothing to fight about. If I had wanted to I could have said I had an uncle somewhere that didn't bother with dirty old coal and ashes at all, but had his own natural gas well and used natural gas; but my nose was sore yet from the last time Ting had pushed it into my face, so I didn't say it.

We went down to the boat house and hired a skiff and rowed up the river to the pond-lily pond. The river was pretty low and it was muddy on the bank of the river -- over knee-deep in mud. Ting got out over the bow of the skiff to pull it up on the mud, so the wash from any steamboat wouldn't send it adrift, and he went in over the knees of his pants, so we thought we had better undress in the skiff, and we did. It felt bully to be undressed outdoors again.

I guess you know how the lily-pond is. On one side is the railroad and on the other side is the river; but between the pond and the river is narrow sand, with willows on it -- bush willows. It makes a bank all around the lower end of the pond-lily pond and ends at the railroad. So me and Eddie and Ting talked it over, and thought we'd better not leave our clothes in the skiff, because somebody might steal them. First we thought we'd hide them in the willows, and then we thought we'd carry them around by the sand spit to the railroad, because the pond-lily roots were over by the railroad more. So we did. We walked around to the railroad and left our clothes there, and waded in. Ting went first.

It was pretty tough. You went into the mud pretty deep, and there were plants that had scratchels on them, and the lily plants and arrow-leaf plants were so thick you could hardly wade. They were all around the shore for two or three rods, and you couldn't see over them. They rustled like corn when we pushed through them. But we knew there was a big clear place in the middle of the pond, so we waded on out to it. It was the place where I learned to swim. It wasn't over head anywhere.

Well, Ting came to the open place first, and he stopped and said:

"There's somebody out there."

Me and Eddie peeked, and there was. Right off we saw who it was -- it was Scratch-cat. She was in where the water was underarm deep, and she was sort of crying, she was so mad. Then we saw what she was trying to do -- she was trying to learn herself to swim. It was enough to make anybody laugh.

It looked like she had been at it a long time, for she was so cold she was shivering. We were near enough to her to see that the black spot on her arm was a mole and not a leaf or a vaccination, and we could see her shiver as plain as could be. The way she was learning herself to swim was this: she put her hands out in front of her and sort of jumped off her feet and then kicked and pounded the water and went down under. I guess you know how that feels. You can't get your head above water when you are that deep unless you stand up; so you paw in the mud, and get scared because you can't get to your feet. Dell Brown would come up scared to death, and spit and blow, and sort of cry, and shiver, and then she would do it all again.

I guess it was pretty tough. Every time she went down she must have got scratched up by the weeds with scratchels on them -- some kind of smartweed -- and she was scared and chilly. It was mighty funny. I guess I laughed out aloud.

Anyway, all at once she saw Ting and us. She ducked like a shot, until only her head was out of water, and me and Eddie laughed. But Ting didn't. He pushed me and Eddie back and said:

"Hey! Scratch-cat! Wait; I'll show you how to swim." Only, he said "I'll showr you how to swim," the way he always says "show."

So he slid his hands out on the water and turned on his side and swam towards where she was. He didn't mean nothing. All he meant was to show her how to swim, because she would never learn the way she was trying. But Scratch-cat turned and held her arms straight out in front of her and hurried for the shore, pushing the weeds away with her hands.

Ting kept telling her to wait, and once he came up to her, and she turned and hammered him with her fists, crazy mad, and he let her go on. The weeds must have scratched her pretty bad, ripping through them that way; but she got to the railway track and began putting her clothes on fast. So Ting said:

"Garsh! I bet she gets our clothes and hides them or something!"

So me and Eddie and Ting hurried to where our clothes were and dressed. We got most of our duds on and were putting on the rest, when we heard somebody yelling. It was a woman, and she was over on the river road, across a cornfield from where we were, and she was yelling like she was being murdered. I was mighty scared. All I thought of was that whoever was murdering her would murder her and then come over and murder us.

I guess Eddie thought the same thing, for he got white and started to run down the railway bank toward our skiff. So I started after him. But Ting he started to run the other way, down the bank to the cornfield, towards where the woman. was screaming. He rolled under the bob-wire fence and started down between the cornrows as hard as he could go. Me and Eddie stopped and looked, and then we went after him, only slower. When we got deep into the corn we got more scared. We didn't like to be so far from where Ting was, with a woman screaming, like that and being murdered. So I hurried up, and Eddie came along, blubbering. I told him to shut up.

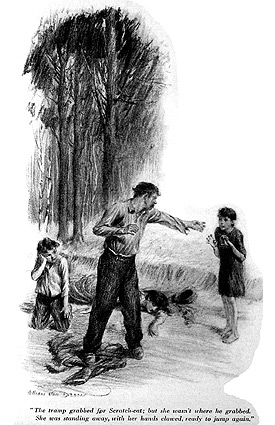

We came to the edge of the cornfield and stopped. It was Miss Goosey, and a tramp had her by the throat, trying to make her stop her yelling. And just then Ting jumped on the tramp. He had a rock, and he lammed at the tramp with it and hit him on the arm. So then Miss Goosey went limp and stopped yelling, and fell in a pile on the road, because the tramp let go of her and she fainted. The road was all tramped up and covered with walked-on goldenrod Miss Goosey had been getting; but the tramp reached around and grabbed Ting and got him by the neck and began to pound his head. Me and Eddie crouched down and looked between the boards of the cornfield fence, because we was too scared to run away.

Ting done the best he could, but it wasn't much use. He was getting killed, I guess. But all at once Scratch-cat came a-sailing out of the cornfield and lit on the tramp with both hands. When her eight claws came raking down his face he let loose of Ting and grabbed for Scratch-cat; but she wasn't where he grabbed. She was standing away, with her hands clawed and her head sort of pointed at him, ready to jump again. So Ting picked up the rock and slung it, and caught him in the back of the neck. He hollered like a bull and turned, and Scratch-cat went at him and raked him on the side of his face. He lammed at her, and I guess he caught her on her brittle rib, because she hollered.

She didn't care what happened, I guess, when he hit her brittle rib, so she went right at him, and Ting made a dive for his legs and got a hold on them. The tramp fought good and hard. He went down, but he kept on fighting; and Ting hollered for me to get a rock and whack the tramp on the head with it. Maybe I would have. I don't know. Just then a top buggy came around the bend of the road, and the tramp showed all he was worth and beat off Ting and Scratch-cat and cut into the woods. We heard him cracking the brush as he scooted, and that was all we knew about him.

Well, the man in the top buggy was Professor Marston; and it wasn't so funny he was in it, because he had wrote Miss Goosey he was coming down and she had gone to meet him. I guess his other sweetheart had got sick of him or something. So he got out and picked up Miss Goosey and fetched her to, and Ting told him what had happened. He said he was much obliged, or something like that, and then he went to where Scratch-cat was sitting on the side of the road, with her hand where her brittle rib had busted. So Ting went over there too.

"Garsh! I'd of been killed if you hadn't come!" he said. But she stood up and looked at him.

"What'd you come swimming at me when I was naked for?" she said, and she was as mad as hops. I guess her rib hurt her and made her sort of crazy mad, and Ting was the first one that came near her, so she picked on him. "Why'd you dare?" she screeched at him. "I'll show you not to!" -- or something like that.

So she went for him. She didn't scratch, either; she used her fists. She fought like crazy, and got her leg back of his, and threw him and piled on top of him. He had to fight as hard as he knew how to, and it was all right, because she wasn't a girl -- she was something crazy mad. It was a quick fight and a good one, and then Professor Marston grabbed Scratch-cat by the shoulder and pulled her off Ting; but that didn't matter, because the fight was over anyhow. Ting had said: "Enough! I won't do it again!"

Well, as soon as Professor Marston had stood Scratch-cat up, she turned white and fell down. She had fainted. It was a good deal of a mess-up. Miss Goosey had got hysterical, and was laughing and crying so she couldn't put her hair switch on her head, and Scratch-cat was stretched out fainted, and I guess Professor Marston was never so busy in his life before. He sent me and Ting over to the pond-lily pond for a hatful of water, and while we were gone he hugged Miss Goosey until she wasn't hysterical, because I guess that was what she needed to cure her, and then he soused Scratch-cat with the water and she came around all right. So he took Miss Goosey and Scratch-cat back to town in the top buggy, and me and Ting and Eddie went back to our skiff and rowed home.

Ting was pretty quiet. I guess he thought Professor Marston and Miss Goosey would tell all over town how he had been licked by a girl; but he told me and Eddie he would kill us if we told it, so we didn't. But neither did Professor Marston or Miss Goosey. The reason was that Scratch-cat told them not to tell she had been fighting. Miss Goosey told Ting so.

I guess that's all. After a while Scratch-cat's brittle rib healed up again and she didn't have to stay in bed, and I was going downtown on an errand past her house, and I saw Ting in her yard. They were playing mumbledy-peg. So after that she played with me and Eddie and Ting, and pretty soon with Mamie Little and my sister and the other girls, and she was almost the one they liked best.

So one day Ting said to me and Eddie:

"Don't you darest yell at me that Scratch-cat is my girl!"

"Aw! I never yelled it!" I said.

"You better not!" he said. "I dare you to!"

So then I knew she was.

www.ellisparkerbutler.info

Saturday, October 07 at 5:42:11am USA Central